[Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared on Streets.MN, an urbanism blog covering Minnesota cities. While the examples here are in St. Paul, the lessons are equally applicable in Louisville. It appears here with permission.]

Compromise is the hallmark of politics, so when it comes to street design, it’s tempting to dole out design features like treats to unruly children: a new crosswalk for you, a drive-thru for you, a bike lane for you, a parking lot for you. There, now everyone’s happy!

And if you’re not satisfied with the outcome of the project, well, the city tried to do the best it could. Everyone got a little bit of something that they wanted, so quit complaining! So many street design conversations end up this way, with nobody really satisfied but nobody getting officially screwed.

The problem is that for a good urban street, this muddy “middle ground” between “walkable” and “driver’s paradise” can sometimes be the worst of both worlds. And as I’ve been traveling around Saint Paul lately, I’ve noticed one particular aspect of street design where the city is about 80 percent of the way to designing a successful street. But much of the time, it’s the last 20 percent of the design that is absolutely crucial to the outcome. I think of it as “the critical ten.”

The Critical Difference Between 30 and 20

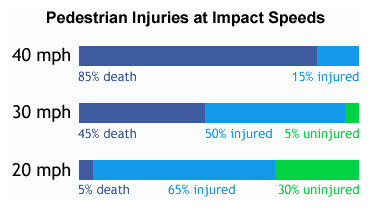

I’m talking about traffic speed. If you look at the average speed of traffic on a urban commercial streets, there are a lot of things that begin to change when you slow down cars from the 30 to 35 mile per hour range into the 20 to 25 mile per hour range. Most importantly, perception, reaction time, and crash outcomes are far better at 20 than at 30 mph, while traffic flow doesn’t seem to change very much.

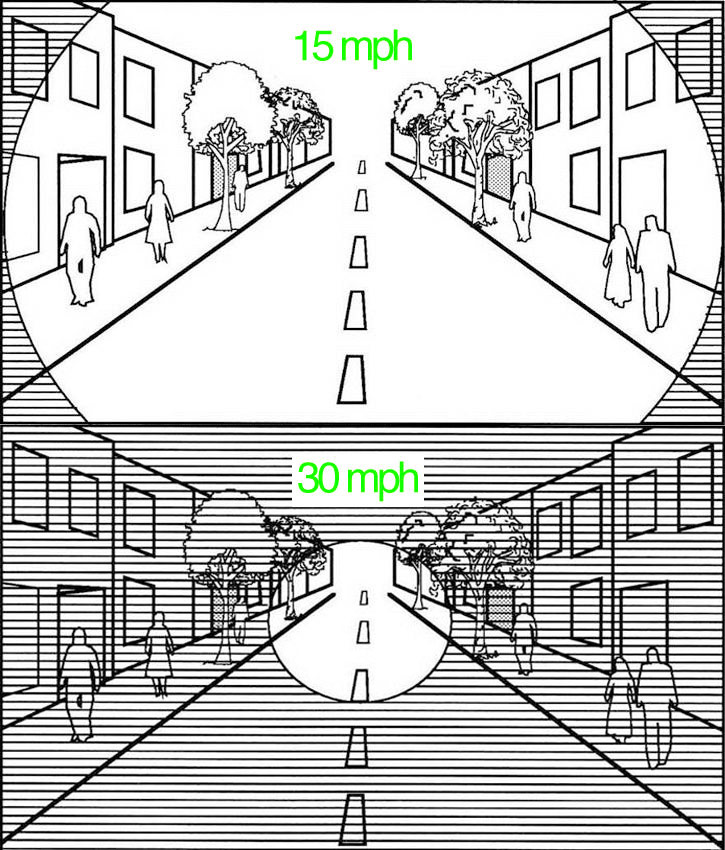

The perception angle is perhaps the most interesting, as illustrated by the chart at right. Driving speed has a dramatic effect on the driver’s “cone of vision.” You can see a lot more detail at 20: people on the sidewalk, a bicyclist in the periphery, or the “open” sign on a storefront. At 30 mph, the window shrinks dramatically.

The same is true for what you might call “reaction time” (see chart below). I’ll often talk to drivers about urban bicycling, and they’ll respond with a terrified story about the time that they “almost hit” a bicyclist that “jumped out” at them. And “I didn’t see them” is a common refrain heard by any police officer investigating a crash. The problem is that once you hit 30+ speeds, it’s a lot more difficult to stop in time to make any difference on a potential crash.

These three factors are the big reasons that crash outcomes vary so dramatically on either side of “the critical ten.” It’s no exaggeration to say that lives depend on getting speeds right.

Slow Speeds and Traffic Flow

At the same time, the big concern for many engineers, drivers, and civic leaders is how lower speeds will impact traffic flow. The amazing thing is that it doesn’t have to make a huge difference. When you’re talking about traffic flow on these urban commercial streets, speed is far less important than delay at intersections. A great example (from the UK) is the main street in the small suburban town of Poynton, which carries more than 26,000 cars a day. They recently and dramatically re-designed the street to create “slow speed continuous traffic movement” by removing stop lights.

The key to the Poynton example is creating a street with low speeds, slowing traffic down below 30 miles per hour. That’s the key to creating streets and spaces where cars and pedestrians, through traffic and local businesses, can really interact.

Here in Saint Paul, the best example is probably Selby Avenue (at least the part running a mile west from the cathedral). To my mind, this stretch of Selby is the best-designed commercial street in the city.

Cars travel slowly, but there are few stoplights. Sidewalks are wide and bumpouts are common. It’s easy to walk, cross the street, and even (relatively) easy to park if you’re willing to walk a few blocks (which many people are because of the nice sidewalks).

And not everyone will agree, but I enjoy biking down Selby, mostly because of the slow speeds and careful drivers. Twenty years ago, if you had told people that Selby and Dale would be one of the most thriving commercial spots in Saint Paul, few would have believed you.

Selby’s slow speeds don’t seem to affect its overall traffic volume, and the street carries around 6,000 cars a day through this stretch, as well as a high-frequency bus line. Similarly, the eastern portion of Grand Avenue (which also works well, in my opinion) carries around 11,000 cars a day. Both of these streets are comfortably in the 20 mile per hour range, and are thriving economically.

For comparison sake, Smith Avenue (from the High Bridge to Annapolis) and Rice Street (from Como to Maryland) carry about 10,000 and 15,000 cars per day, respectively, and are both struggling economically. Meanwhile, the Poynton UK example has combined sub-20-mile-per-hour design speeds with 26,000 cars per day (about the same as Snelling Avenue). Believe it or not, designing a street with slow speeds doesn’t have to have huge impacts on volume.

Why 20 is so Critical

But doing the little things to push the design speed of a commercial street into the “critical ten” range can revolutionize our cities. Both Smith and Rice streets are long struggling commercial corridors with lots of historic buildings and vacant storefronts. Both streets are cases where the city has tried to design a street that would work for drivers, businesses, and pedestrians alike, but hasn’t reached a design solution that encourages foot traffic that would support small businesses. For both streets, it remains difficult to cross the street, and both places cars are still traveling at dangerous speeds.

Grand Avenue is the perfect case study for why the critical ten is so important. For key stretches of the street (e.g. east of Lexington), Grand is a street that works very well for everyone. Cars travel slowly, you can parallel park, cross the street, and there are few accidents.

As you begin to travel west, speeds on Grand Avenue increase. There are large stretches where the street “tips over the threshold” and loses the virtuous cycle of pedestrian safety, street life, and thriving local businesses. Anytime you see those (oft-mocked) orange pedestrian flags, it’s a sign that we haven’t quite reached the design speed sweet spot.

Cities like Saint Paul have been trying for years to design streets that move cars while creating thriving spaces that support small businesses. It’s frustrating to see so many places that are almost well designed. These streets are victims of compromise, almost-but-not-quite safe for pedestrians and almost-but-not-quite good for small businesses. Sometimes, small differences in design can pay big rewards. I believe “the critical ten” is a key missing piece for our main streets, and that if we reduce speeds down to the 20 miles per hour range, our cities might find the renaissance they’ve been looking for.

[Top image: New Yorker’s rally for safe streets in Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza. By Dmitry Gudkov / Flickr.]

I always think about this when I’m walking on Bardstown Road. Though it could use more crosswalks I find a major component of what makes walking around Bardstown Road (from the Loop to Broadway) pleasant is the low traffic speeds of the cars. During rush hour with bumper to bumper traffic it’s still a little quieter, feels less crazy, and even without crosswalks it’s usually manageable to cross the street. Every once in a while I remember that the speed limit all the way down Bardstown Road is 35. If cars actually drove 35, or 40+ like they do in many 35 mph zones, the atmosphere of the street would be severely impacted in a negative way. The streets-cape obviously has a major influence on driver speeds because even during very non-peak traffic hours such as late on a weeknight, I find most cars are usually doing no more than 30.

Unfortunately it seems many of our interior city streets are still seen as commuting zones, as evidenced by the Brownsboro Road tree removal controversy last year.

The 20 mph speed limit is the linchpin for pedestrian/ bicycle safety in Stockholm. One of the beauties of 20 mph is that you no longer require dedicated bike lanes… because there is no longer a significant need for cars to pass bikes.

20 mph is too slow. 25 can be fine IF street conditions warrant it, but 20 just feels like a snail’s pace.

Again Eric, it’s a question of whether local residents would prefer to cater to the local residents and businesses or those who are simply passing through.

20 mph doesn’t need to feel like a snail’s pace, it’s all relative.