On Wednesday, May 25, Jefferson Circuit Judge Judith McDonald-Burkman denied an injunction to dismantle and store the Confederate Monument on Third Street near the University of Louisville‘s Belknap Campus clearing the way for Metro Louisville to remove and eventually relocate the 121-year-old monument.

“I am pleased with the judge’s ruling that the city owns the monument and has the right to move it,” Mayor Greg Fischer said in a statement that Wednesday afternoon. “We will await the judge’s final written ruling before taking next steps. In the meantime, my team will be working with the Commission on Public Art and the University of Louisville to evaluate disassembling, restoring and relocating the monument.”

Plans to remove the obelisk were announced jointly by city and university officials on Friday, April 29, but a lawsuit was quickly filed, slowing down the process. News of the Confederate Monument’s pending removal quickly spread across the country, appearing in ABC News, Fox News, Reuters, the Huffington Post, and many others.

In any case of removing or relocating a piece of Civil War history nationally, the conversation naturally focuses on civil rights, states rights, and the heated sentiments of those for or against the action. Controversy makes for easy news. But also because it’s the right thing to do in most of these cases—and in this case it’s long overdue. (We’re not digging into the traditional complexities of moving Confederate monuments here—there has been much written on the topic already. And the Louisville Forum will formally discuss the move at its upcoming June 8 meeting.)

In Louisville, the city, university, and larger community have struggled over the years to sidestep the monumental issue by renaming Confederate Place (formerly Park Place) to Unity Place in 2002. The university built Freedom Park a block north in an effort to “provide a more complete historical account” of Louisville’s civil-rights struggles in the context of the Confederate Monument. That park highlights local civil rights leaders and tells the history of Louisville on a continuum from slaveholding settlement to “a diverse metropolitan area still struggling to enact equal rights for all its residents,” according to the university. Freedom Park was renamed to Charles Parrish Park in 2015 to celebrate the scholar and first African-American department chair at the university. The University of Louisville only began admitting African American students in 1951. Still, the stone obelisk stands out front and center as a civil rights sore thumb.

The How and Why of a Move

But there’s an entire story at play here that hasn’t been fully explored: while the ends may be justified, by what means are we removing the Confederate Monument? How we remove the monument is just as important as why we remove it. Our actions will determine the history being made more than our words.

The city’s impulse to suddenly move the monument appears to be less about civil rights than it is about traffic. It’s a reflection of how Louisville’s built environment continues to be shaped by the automobile. According to Mayor Fischer’s official remarks in announcing the move, the first reason stated is to speed cars through the area: “There are practical reasons for why this statue should not be here,” Fischer said. “Like the traffic complications it causes turning in and out of the beautiful new Speed [Art Museum].”

At the April 29 press event, the city and university said they had been working on the move for “several weeks,” but already appeared to have a complete road design worked out for the state highway. Given the complexities of working with the state on road changes, it’s hard to believe that this process wasn’t in planning for a considerable time—without public input—given that work is expected to be underway this summer.

It’s as if the dream of Louisville in the 1950s has finally come true. Plans first thought up by the car-crazy engineers of over half a century ago are finally being realized 60 years later. Once the monument is disassembled and put in storage, crews will be sent in to straighten out and smooth the road bed, cut off Unity Place, and reconfiguring a turning lane into the Speed Art Museum’s parking garage. There’s no consideration for pedestrians or bicyclists in the new design, and there’s no public space. The move essentially will erase any trace that there ever was a monument of any kind at this location. With a fresh layer of asphalt, Third Street will be like any other street in Louisville or anywhere else.

In the end, the manner in which the Confederate Monument is being removed offers no healing for those on either side of the issue—and it paves over the meager public space the monument once provided for more roadway, making driving easier and walking or cycling even more dangerous than today.

Already, Third Street is a dangerous speedway, with 2,100 feet of uncontrolled vehicular straightaway between Brandeis Avenue and Eastern Parkway (save a beg-button operated crosswalk at one point) that allows motorists to speed through an area packed with people and parks. The posted speed limit along Third is 35 miles per hour, but it’s a common sight to witness speeds significantly higher than that through the corridor.

Despite well-appointed new streetscapes at the University of Louisville, the area still faces many walkability challenges. Rather than try to significantly calm traffic, the university’s approach to pedestrian safety has been to install fences that create barriers on the street, herding pedestrians in a controlled flow to the next crosswalk. This approach ignores the underlying bad road design and tacitly accepts that Louisville’s streets are unfit for people.

An Impromptu Proposal

Instead of ripping out the monument and paving over the site, I propose reevaluating whether the urban renewal scheme that shaped this stretch of roadway from the 1950s through the 1970s has been effective in creating a more livable Louisville. How can we redesign the larger street here to be inclusive for everyone, promote the walkability of the university’s campus and nearby Old Louisville, and build off the growing student population living on or near campus?

Rather than ripping out the Confederate Monument and paving over its site, I propose re-imagining a new sort of monument for the site that serves to unite the community, maintains a civically oriented public space, and serves as a way to interpret the long-fraught site’s historic context.

There are plenty of ideas readily available for a new memorial, from a general memorial to unity or peace, to a tribute to Louisville native son Louis Brandeis, who was named to the Supreme Court 100 years ago this week. Perhaps the Speed itself could weigh in, or a design competition launched.

The act of removing the monument means we could lose cultural memory, but the act of paving it over almost guarantees it. By replacing the monument with a new concept, we have the chance to contextualize the motives of this period in history and those over the past 120 years in a way that’s respectful of the future.

Only when we remove the monument and treat its site with dignity can we can begin to address cultural memory and memorialization as a united community, not as disconnected, disparate drivers.

Six Score and Nine Years Ago

The story of the Confederate Monument begins when Louisville is at a historic high. In 1887, Louisville was experiencing a boom, with the successful completion of the five-year long Southern Exposition thrusting the city into the international spotlight. The city’s population was surging—since the end of the Civil War, Louisville’s population had roughly doubled to over 160,000 people. Development was keeping pace and spirits were high.

According to Bryan Bush’s book, Louisville’s Southern Exposition:1883–1887, the initial plan of the world’s fair was to showcase the southern cotton industry “from seed to loom.” Bush pointed out that “many of Kentucky’s political and civic leaders after the Civil War were ex-Confederate soldiers” and there was some hope to establish Louisville as the prime city of the south. But after Atlanta beat a slow-to-act Louisville to the punch in 1881 with its International Cotton Exposition, Southern Exposition founder Henry Watterson, himself a Confederate veteran and chief editor of the Courier-Journal, refocused the show on the industrial innovation—of both the north and south, but still with a distinct southern slant. The Civil War had been over for 22 years at this point, and Louisville had rebounded well thanks in large part to its neutral stance during the war.

In this boomtown context, in June of 1887, the Women’s Confederate Monument Association was organized with the intent of building a Confederate Monument in Louisville with a budget of $12,000, an endeavor that would include dozens of social events in the coming years and involve some of the biggest names in Louisville, including having the full weight and support of Watterson and his newspaper.

(In the end, the association was able to raise $10,200, and it continued holding fundraisers after the monument was installed to pay off the balance. In today’s dollars, that roughly means the group raised about $275,000 of its $325,000 goal by the time the monument was complete.)

The Booming Hinterlands

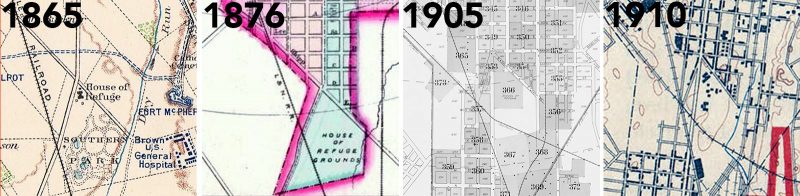

Back then, the area around the current site of the Confederate Monument was very much the edge of town. Just a few blocks south of the 45-acre exposition grounds, maps from the 1880s show only a smattering of buildings filling a grid of lettered streets—the city was literally growing faster than it could come up with names for its streets.

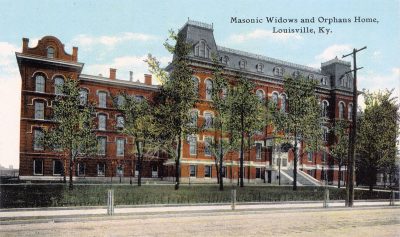

The area’s two institutions included the Masonic Widows & Orphans Home filling a large Mansard-roofed structure at Second Street and C Street (later Avery Avenue then Cardinal Boulevard) and the House of Refuge, renamed the Industrial School of Reform in 1886, a sort of juvenile detention and education center on the current site of the Belknap Campus. (The University of Louisville purchased the property for its campus in 1923 when the School of Reform moved again to the city fringe in Lyndon. The first classes opened in 1925 and architect Arthur Loomis‘ Speed Art Museum was built on the site of its administration building in 1927.)

Construction began on the House of Refuge in 1860, but the property was seized by the Union and used as a hospital for soldiers until the war ended in 1865, adding another layer of complexity to the Confederate Monument site.

But while this area was on the edge of town, the city’s momentum was clearly headed its way. The exposition grounds would soon be redeveloped into St. James Court and Central Park, making it the city’s premier address. In 1889, Mayor Charles D. Jacob had purchased land that would become Iroquois Park (first called Jacob Park) miles to the south, and in 1891, Frederick Law Olmsted was hired to design the city’s ambitious new park and parkway system that would shape the city’s suburban growth for the next century.

Third Street Triangle Park

Among the parks that Olmsted and his successor firm Olmsted Brothers designed is a triangular green space beginning at the Confederate Monument stretching south to Eastern Parkway. Over the years, it’s been known as the Third Street Triangle, Third Street Playground, Triangle Park, and, today, Stansbury Park.

That notion of a park here was set out in deed of the House of Refuge when the city granted it land in 1860. According to a National Register document describing the Belknap Campus, “the City Council required that as compensation for its gift to the House, the board of managers ‘set apart and layout not less than forty acres of said land in one body and ornament and embellish it for a Public Park.'” But the park didn’t appear overnight. The first park on the House of Refuge grounds was simply called Southern Park on its southeast corner. Triangle Park would come years later.

Triangle Park was authorized by the Board of Managers of the Industrial School of Reform on July 6, 1887, according to an article in the Courier-Journal. A resolution raised by General John Breckinridge Castleman was adopted, stating that if the city agreed to purchase and improve up to 100 acres adjacent to the school, it would provide a park without charge to the city for ten years. But a decade later in May 1894, the Louisville Park Board was still debating such a green space.

At that time, Third Street south of the Confederate Monument was the route to “Grand Boulevard”—more simply known as “the boulevard”—the 150-foot-wide thoroughfare today called Southern Parkway. While the boulevard was paved and a popular destination for cycling by the early 1890s, it was largely disconnected until a direct path through the House of Refuge was secured. Early maps show an unlabeled road running along the Park Place (today’s Unity Place) alignment from the House of Refuge south from Third. Once Third Street was extended, it created a triangular patch of leftover land that was slated for the park.

It wasn’t until 1900 that land was officially transferred to the city for the park, despite Third Street’s right of way being extended south some time earlier. In those early years, the triangular parcel was just a wooded lot overgrown with trees, but the Olmsted Brothers quickly got to work once the land was transferred.

The Olmsted design for the triangle featured a simple, formalized layout with a classic pavilion, fountain and splash pool, two lawns, and play areas. A train station was located at the southern side.

Today, plans are being pursued to restore the park to its original Olmsted design. Much of the original landscape has been lost in the past half century and a dormitory, now demolished, was even built in the middle of what was once park space.

Choosing a Site and a Monument

Three sites were initially considered for the Confederate Monument, according to a January 1891 Courier-Journal report: “Third and Broadway, intersection of the boulevard and Third, and a circle of ground beyond the railroad crossing on the boulevard.” As mentioned above, the boulevard is what is today Southern Parkway, but it often refers to Third Street south of Brandeis in old texts, meaning the second site, which was the preferred option of the Women’s Confederate Monument Association, is the site on which the Confederate Monument was ultimately built. The women’s association is also reported to have considered Cave Hill Cemetery as another appropriate option.

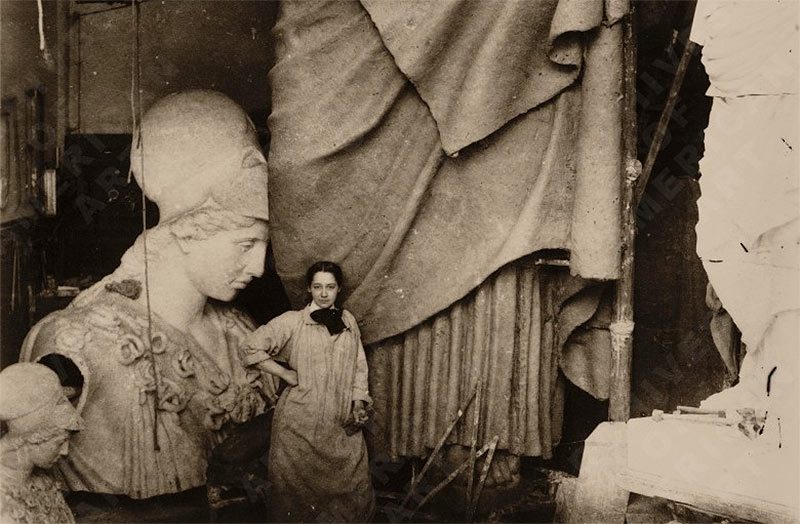

A competition was held for the Confederate Monument’s design, and more than 20 plans were submitted. The women’s association had selected a group of architects to vote on the best design, scrubbed of any identifying information on the designer. After a vote, a design by Louisville sculptor Enid Yandell was selected unanimously by a the committee.

“The monument is to have a base of 42-feet in diameter, and it to be seventy-five feet high,” a September 20, 1894 Courier-Journal report read. “The base is to be built of Bowling Green white limestone, the pedestal of North Carolina gray granite, and the column of red Quiney granite, which will support a bronze figure of fame holding a wreath in one hand and a confederate flag in the other. At the base of the monument there will be five bronze candelabra, each fifteen feet high.” The column would be wrapped at two points in bronze banding and be topped with a Corinthian capital.

Meet Enid Yandell

Enid Yandell won the Confederate Monument design competition when she was only 24 years old, a remarkable achievement in a field dominated by men in the 19th century.

In 1891, two years after graduating with a first-prize medal from the Cincinnati Art Academy, Yandell was working on her first professional commission, a series of caryatids for the famed World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, according to the Filson Historical Society. The Filson commissioned a statue of Daniel Boone to be displayed outside Kentucky’s pavilion at the Columbian Exposition, earning Yandell several ribbons from fair judges. That statue would later be bronzed in 1906 and placed in Cherokee Park. By 1898, she was achieving great fame and was the first female inducted into the National Sculpture Society.

Locally, Yandell, herself from a prominent Louisville family, realized the Daniel Boone statue and the statue of Pan atop Hogan Fountain in Cherokee Park and Wheelman’s Bench in Wayside Park, among other projects.

Shenanigans over the Monument Choice

But as you know, Yandell’s monument was never built.

A faction within the Women’s Confederate Monument Association turned on Yandell and her design. They claimed that her gender and young age made her unqualified to design such a monument in the first place.

In an attempt to ease tensions around the design, the association’s Executive Committee asked three leading architects for their opinions of the competition designs, and Yandell’s column was again picked as the best.

But critics could not be silenced. At a heated meeting of the women’s association on October 1, 1894, the membership remained bitterly divided over the design and Yandell’s qualifications as a sculptor. Cries of “We want a soldier on the monument!” filled the meeting room.

That evening, the membership voted to overrule its committee of architects and its Executive Committee to scrap Yandell’s design in favor of the as-built design by Michael Muldoon of the Louisville-based Muldoon Monument Company. That company, founded in 1854, is still in business today as Muldoon Memorials.

There was clear fraud in the vote, as a Courier-Journal article (carrying six headlines) the following day pointed out: 36 votes were cast but only 32 members were present and two abstained. After the vote, those opposing quickly left the room so no other vote could be taken. The incident represented something of a scandal within the society circle.

By the following Friday, the association had apparently come to terms with the coup and another, much calmer vote made the decision to scrap Yandell’s design final.

The book Visual Art & the Urban Evolution of the New South contradicts this Courier-Journal account, stating that Yandell’s material choices (namely the limestone proposed for its base) were rejected by a board of architects, that the unaccounted for women in the association’s vote had simply left early, and that Yandell eventually withdrew her design following the controversy.

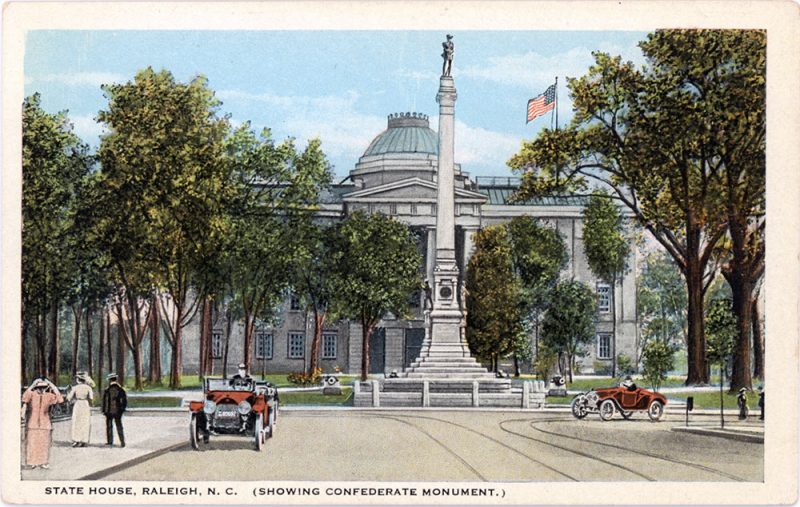

A Carbon-Copy Monument

Muldoon was prepared to step up with his alternative monument design because it was a nearly identical copy of another Confederate Monument his company was building at the State House in Raleigh, North Carolina, complete with statues of Raleigh, North Carolina, soldiers. Muldoon’s Raleigh design was selected in a bidding process nearly 6 months before the identical design was voted on in Louisville. (And Raleigh reportedly paid $25,000 for their version, while Louisville’s budget was $12,000—perhaps indicating a hometown discount or that a second casting was much cheaper than original statues.)

Raleigh’s monument opened in May 1895, slightly before Louisville’s opened later that summer at the end of June. Adorning Raleigh’s monument are three figures sculpted and cast by Munich-based Leopold Von Miller II—the same three statues cut and paste onto the Louisville version. The stonework on the two obelisks themselves varies slightly, likely a reflection of the overall price tag and a result of local variation. Over the years, however, Raleigh has clearly better maintained its monument, as is clearly seen in a comparison of the two obelisks.

The Muldoon Monument Company, of course, made monuments as a business, and a walk through Cave Hill Cemetery will easily show off a good selection of their best work. But they also advertised in Confederate newspapers and magazines about their monument work, which included many Confederate monuments in other cities such as a smaller obelisk in Nashville, Tennessee—Confederate monument building in the late 19th century was clearly a big business.

Another differing detail in Louisville’s design is the island in which the Confederate Monument sits. The 48-foot-diameter stone ring defined a perimeter for the monument and included four ornate wrought-iron lamps set atop four stone blocks, added slightly after the monument was completed, according to early photos. One small note in the August 10, 1897 Courier-Journal noted that the women’s commission had “written to Mr. Olmsted…asking him to submit plans for a suitable fence.” Perhaps as a consolation to the clearly corrupt selection process, some news accounts attribute the highly ornate candelabras surrounding the monument to Enid Yandell. But those, too, were destroyed by the coming age of the automobile, as we’ll soon see.

A Lesson in Urban Design

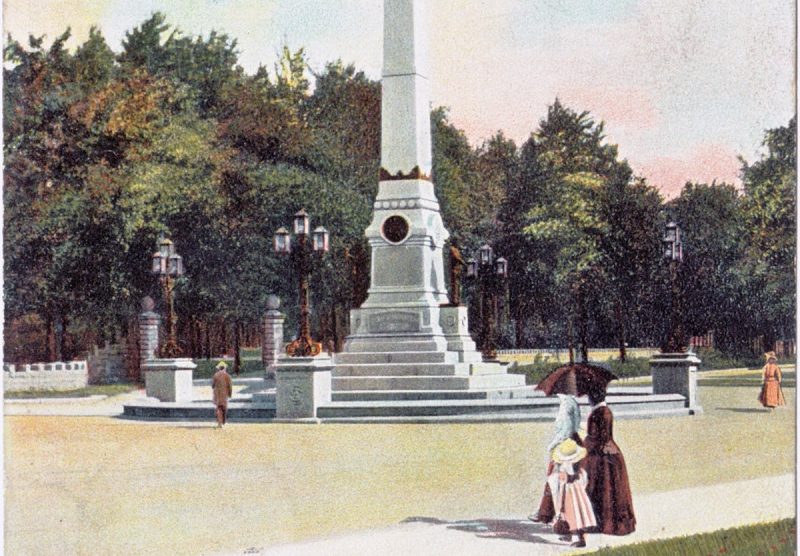

Sometimes old depictions of familiar places give us a glimpse into how daily life—or the way we experience the city—has changed over time. Take the above view, for instance, showing the Confederate Monument with the Industrial School of Reform in the distance. While it’s a lovely colorized view, it’s the people in it that give us additional information about life on Third Street.

First, we can fully appreciate the scale of the perimeter ring and the stone blocks supporting the lamp posts thanks to a man standing next to them. What might otherwise look like a small stone curb is revealed to be a bench-height perimeter ring and the lamp blocks are easily a massive six feet tall. Those oversized stone blocks were carved with the insignia of CSA, for Confederate States of America. Many early views show that this ring was neatly composed and lushly landscaped. That ring spans a 48-foot diameter, which would have given the overall 75-foot-tall monument a, well, more monumental presence along Third Street.

What’s more revealing is how people are interacting with the street on a bright and sunny day. You can see a family out for a stroll in the foreground, the aforementioned man taking in the monument clearly standing in the street, and, most importantly, a woman in a dress on the right side casually walking up to the monument in the middle of the street.

Now that you’re focusing on those people, you might think it dangerous that people are hanging out or casually walking in the street, which it likely would be today. But around 1906–1910 when this view would have been taken, streets served a distinctly more human purpose. The average Louisvillian was much more able to enjoy the public realm of the city, to take in the city’s public art, architecture, and its monuments, than we are today. When you design streets solely for cars, the niceties of urban design like the Confederate Monument end up as traffic nuisances.

A century ago, the monument really did create a sort of bottleneck in the road—and that’s likely the point of its original placement: to force people to take notice. It’s very common for such monuments to be placed as “terminated vistas“—the object at the end of a long view or frame of reference. In urban design, such a placement adds to the object’s visual significance and can create an exceedingly beautiful urban composition. Think of another memorial to a Confederate soldier in Louisville, the Castleman Monument in the Cherokee Triangle. The placement of that monument, located in the center of a roundabout, adds to the overall visual effect.

But the Confederate Monument was never designed with the added space of a roundabout or extra road width to compensate for the 48 feet it took from the Third Street road bed, which ultimately would create problems half a century later when speeding cars through the city proved the highest goal of city planners.

Speed through a civically charged area like at Third Street and Brandeis is often the biggest determinant of a successful place. A place for people must move slowly, and that requires intentional design. Were we to design a high-speed thoroughfare through any of the world’s great plazas, they would become just like Third Street. But slowing traffic—sometimes quite substantially—and making a street into a place is why we love the great urban spaces of European cities. The monument’s location along Third could rival many a European plaza: it features the city’s art museum, recently expanded, the city’s university, two public parks, one by Olmsted, a theater, and forms the gateway to historic Old Louisville and the terminus of Eastern Parkway. It’s hard to pack more significance into a couple blocks.

The Automobile Age Arrives

Following the turn of the century, Louisville and the nation began to be increasingly dominated by the automobile and an unflagging pursuit to reshape the city to fit more and more cars at faster and faster speeds.

By the late 1940s, calls were being made to move the Confederate Monument to improve traffic flow for motorists. “We can see nothing offensive, sentimentally, in the suggestion that the Confederate Monument be moved out of the way of Third Street’s heavy motor traffic,” a September 4, 1947 editorial in the Courier-Journal read. “The average automobile driver whizzing around it thinks not of its fine significance but of its inconvenience and danger.” Sadly, that notion is true of just about anything lining Louisville’s streets today, from historic architecture, to trees, to people.

The writer went on to note that when it was erected in the 1890s, bicyclists were able to safely take in their surrounding built environment—and Third Street was a major bike thoroughfare through the city. “The monument got in nobody’s way in those days, and people had time to give a thought to its meaning,” the article continued. Happily, that notion is still true today that those who get around by bike have much more time to enjoy the beauty of Louisville.

Still, opposition stalled those initial plans, and in 1948, Mayor Charles Farnsley, who lived on Confederate Place and was a staunch supporter of keeping the monument in place, took office. By 1953 the next administration under Mayor Andrew Broaddus was back with more plans to move the monument.

In a Courier-Journal article dated September 18, 1954, a city engineer announced plans to widen Second, Third, and Brandeis Avenue to handle new motor traffic generated by the nearly complete Eastern Parkway overpass. Third Street would be reconfigured from four lanes to six. Mayor Broaddus also made an official call to move the Confederate Monument from its location in the middle of Third Street to a new spot at the tip of Triangle Park (now Stansbury Park) to the south. In an attempt at appeasing Confederate groups, Broaddus also proposed renaming the green space Confederate Memorial Park.

Still, local resistance to the move was strong and by October 14, 1954, the Courier-Journal reported that a proposal to “trim” the island that surrounded the obelisk was raised to counter Broaddus. The monument was originally surrounded by a 48-foot-diameter stone circle, but removing it reduced the space the monument needed to about 22 feet. Some proposals to create an elliptical ring around the monument were also studied but ultimately abandoned.

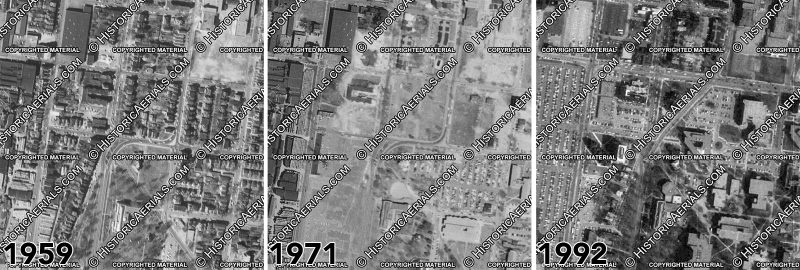

By 1956, the city had made no progress on Third Street. A May 10, 1956 Courier-Journal article noted the beginning of the urban renewal era around the University of Louisville as a growing student population had administrators looking for space to expand. Back then, the university existed only below Shipp Avenue in a compact triangular space, but the idea of launching an urban renewal and redevelopment project would eventually clear dozens of houses and shops to make way for a larger campus—and faster roads.

By June 1957, the Courier-Journal reported that while Broaddus was unsuccessful at getting the monument moved, he had negotiated the removal of the Confederate Monument’s island. By summer, work was well underway to reshape Third Street and streamline motor vehicles through the area. Shipp Street was closed at Third Street, and Third’s road bed pulled east at Brandeis, beginning to resemble the modern layout in the area.

The resulting layout would remain in place for another decade before the city was clamoring again for more change and an even more streamlined layout. By the 1970s, the city was in full Urban Renewal gear and nothing was safe from the traffic engineer’s bulldozer.

The Urban Renewal Era

The street overhaul we know today with Third Street forking onto Second dates to the mid-1970s when Urban Renewal clear-cut the “Old Louisville restoration area” and pushed a streamlined “connector road” from Third Street wrapping over to Second Street allowing Second and Third to serve as one-way highways in and out of Downtown Louisville. (Many other changes and realignments meant to speed motorists around Old Louisville were also part of this plan.)

And now with the complete removal of the Confederate Monument, the dream of the 1950s for unfettered car access through the area will finally be realized.

Thoughts on the Future

As history has shown, the Confederate Memorial is not particularly special in its design, and its overall composition has been diminished over the decades. It is not well maintained nor whole in its original design. Decades of civil strife and community protests have shown that the monument is not worth keeping in place, and many more appropriate places exist for its display. It can and will likely be laid to rest with its founders and their ideals in Cave Hill Cemetery.

What is worthy of questioning is the removal of civic space. Why is it that the Confederate fervor of the 1880s made for a better streetscape on the then edge of town than a top-tier art museum, university, and neighborhood make today?

The monument site has gained and lost more public art—from ornate fountains to over-scaled street lamps and now the Confederate Monument itself—than most other places in the city will ever see. This site has clearly been cherished by the community as a significant node since its beginning. But where is there identity left today? Why not create a new monument—a new public space? We’ve completely recreated this urban space twice before, why not remake it one more time in the image of people rather than machines?

Or do we already have our monument? Five lanes wide, double lined, and unstoppable.

Excellent historical article….also, thanks for the photos!! I love learning about Louisville history, and you provided a lot!!

I’m glad most of my CW ancestors are buried on private property. I don’t have to worry from several states away, will they be dug up?

I like the pictures.

Your matter-of-fact statement ~that a faction of women from the WCMA objected to the gender of the designer of the winning monument plan~ needs a primary source reference, please. Yes, a faction of women protested the young age of Yandell, and they objected to the gender of the figure on the capital of the column (a classical goddess instead of a soldier) but where is it written, at the time, that they specified the gender of the designer as objectionable of itself “in the first place”? I am eager to read this source.

…and don’t forget to mention that the winning plans for the monument were co-designed by Enid Yandell and the equally young William J. Dodd, he with a penis, we presume. Which gender were the critics protesting, you say? Dodd even had the unenviable role of being apologist for the design and its engineering specs in the face of the critics.

…I didn’t think my 9:09 pm suggestion was ‘immoderate’ and required moderation.

Excellent read.

Very impressive use of media.

Compelling analysis.

Bravo, Broken Sidewalk!

I sure hope you make money on this site. You are an impressive writer….How about we start a petition to make this site the location of a new Muhammad Ali monument?

Muhammad Ali deserves way

More consideration than a hit and miss redo that shouldn’t be redone, and on a site he likely wouldn’t have warmed to. He was an accessible man. His

Memory should be as well. And Fischer that arrogant butcher of history should have nothing to do with it . Civic is just that. Dictatorial pronouncements that stem from historical ignorance have been the hallmark of his badministration.

Thanks Brandon for

Putting this out there. Like Brandeis, who favored open discussion over enforced silence. That quote hung on my office wall my entire career.

This was a well written and thoughtful article. But I am inclined to agree with ctwhite regarding the unsupported sexism charge and the larger association decision to reject Yandell’s design.

Yandell had already completed commission work for members of the Filson Club. It is certain the officers of the association, among the elite of Louisville, were very well acquainted with her family and her emerging talent.

Ms. Yandell’s mother was heavily involved with the monument association, and the Confederate Veteran reported after the monument was erected than Enid’s uncle David was on the executive committee. It is possible he was not on it when the committee chose Yandell’s design. But officers were chosen once per year. The charge of nepotism has serious merit. Muldoon argued the designer’s name was on the drawings during the selection process.

Muldoon’s design came in at cost, but he did make $1,600 profit. Yandell’s design utilized more expensive granite, was larger and included lamps and a rather large base. Unless Yandell created the sculpture at near cost, her design might really have blown past the $12,000 budget.

Michael Muldoon had consulted with the association as early as 1887. His daughter Anita sang at various times at fundraisers for the monument and also in Raleigh. It is thought Muldoon sent photographs to Von Miller for the Raleigh monument, which apparently included Judge Thompson as the model for the top figure. So North Carolina and Louisville have a Louisvillian at the top of their monuments. This would have been no mistake. Judge Thompson and his wife had fund raised for the monument, including at their home. And his wife was chairwoman of the auxiliary committee.

My take is, based on limited evidence, the whole “blind competition” was a sham. The other 18 designs had little hope of being selected. The executive committee was in the Yandell camp, and the Muldoon camp was better represented in the rank and file of the association. It is possible there was a social class element in play. It may come as no surprise that Judge Thompson was very well respected among the lower social classes of Louisville.

The ballot stuffing charge may have been the CJ generating controversy in support of Yandell. At the very worst a handful of ballots might have been added, but probably not. Yandell was defeated 2-1 by Muldoon’s design. Throwing in a few ballots wouldn’t have changed the outcome.

In doing a bit of thinking about this, having revisited this article nearly a year out from its publishing, I’ve come to a rather dismal conclusion. The university only cares about progress. Or rather, its definition of progress. Which, in this case, means tearing down a monument to an important piece of history, and replacing it with pavement.

This article brought up this sentiment, as it reiterated the fact that the City and University’s priority is a thoroughfare. Consider the lack of accessibility and consideration for bicyclists and pedestrians. People are a resource. Perpetually expendable. But commerce, and the ability for it to flow in the form of traffic, is the commodity.

I had this whole great spiel about the dearth of life, but unfortunately, I’ve forgotten. It was beyond the sanctity and preservation of our history, no matter which side you stand on. It was more of a reflection of how the humanness of those who governed the city had connections to that part of our city’s past. And how that past has been ultimately paved over. And how the lives of those people, and their humanness, has received the same paving over.

It was a great humanist spiel, and I’m sorry it fell apart.