This week we’ve been talking about not just the fate of one century-old building on West Breckinridge Street, but the future of an entire neighborhood. What do we want SoBro—the area south of Broadway between Downtown and Old Louisville—to look like in the 21st century?

In the 19th, SoBro was a leafy suburban enclave of enormous mansions. During the 20th, the neighborhood was slowly flattened out into an expanse of parking that, this year, earned the area notoriety as the nation’s worst “Parking Crater.” We’re now well into the 21st century, and SoBro is changing again. This time, perhaps, into a vital urban neighborhood. And the threatened Puritan Uniform Rental building stands at the center of that transformation.

If you’re just joining us, head over here to catch up on what’s going on with the circa-1917 structure. In short, Spalding University has taken out a demolition permit that would level the site into another asphalt parking lot. But with some neighborhood support, that plan could change.

Last week, we toured the Puritan building with Spalding President Tori Murden McClure. And we’d be remiss not to report that the building was built like a tank. Sure, the structure has its faults, like a leaky roof that’s allowed water to spill into a second floor office, but there’s a lot of potential left in the Puritan’s old bones. So let’s look at what’s left and imagine what might be.

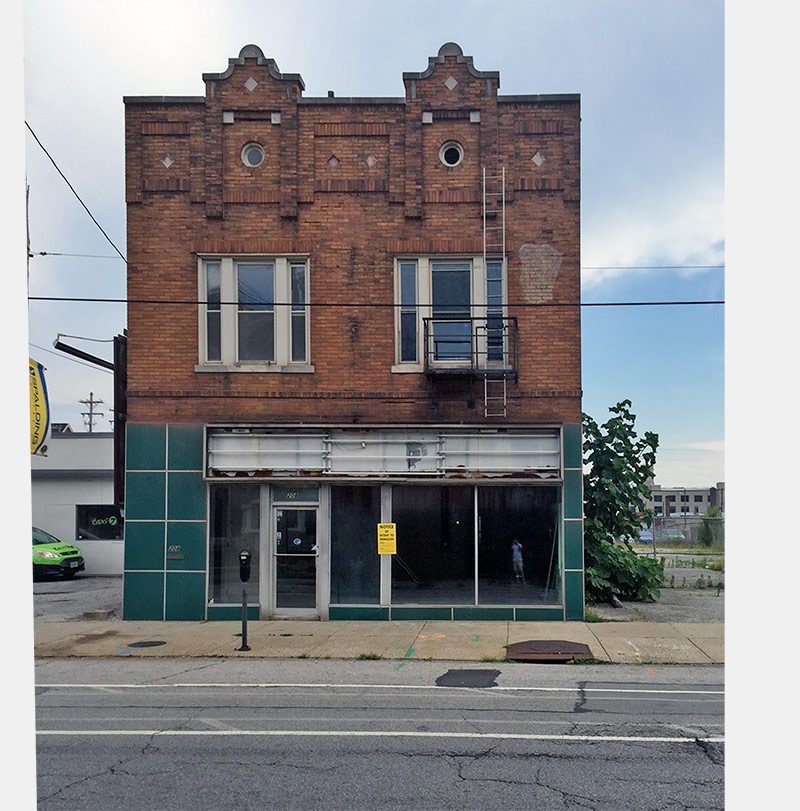

First of all, it’s important to remember that the 1.62-acre Puritan Uniform Rental complex is actually three parts: the orange-brick Puritan building at 206–208 West Breckinridge Street, an empty lot directly west of the site at 210 West Breckinridge, and another commercial storefront at 914 South Second Street, today painted dark green. Each of these pieces has a part it can play.

Puritan style

First up, the Puritan Uniform Rental building. As we noted before, 30-foot-by-200-foot structure was built by architect Oscar Reuter in 1917. The structure consists of a two-story building taking up the north third of the parcel and a one-story section occupying the rest. Together, they cover around 7,200 square feet.

It’s the Puritan building that really brings architectural style to the complex, according to Marty Perry at the Kentucky Heritage Council. Perry helps coordinate National Register nominations for buildings across the state. He first saw the Puritan a few years ago while putting together a nomination for the larger Olympic Building across the street. Those two structures are what Perry calls “Craftsman Commercial” style architecture. “You can see in these two buildings—the Olympic Apartments and the Puritan—some of the hallmarks of the style,” he told Broken Sidewalk in a phone call last week.

“The parapet has these sort of bump-ups,” Perry explained. “They look like something that you’d see on a fancy movie palace between the two World Wars—that’s something that I see on nice urban movie houses in the 1920s.”

At the Puritan, most of the original style is still present on the second floor and cornice of the structure (the first floor has been covered over by a new storefront during a 1950s makeover). “The facade plane is recessed and projecting all over the place,” Perry continued. “It required some pretty sophisticated masonry skills to achieve that effect.”

Perry added that this brickwork isn’t often seen in modern buildings. “It called for real skillful brick laying work that somebody had to pay extra for, or the brick mason had to work harder on to achieve some sense of depth or texture,” he said. “That becomes a decorative theme in the building—it’s almost a sculptural thing.” He noted that small limestone insets help guide the eye around the facade and soldier courses—bricks layered lengthwise next to each other—help define the style.

“The brick and limestone work together to achieve this highly decorative top to the building that didn’t require expensive custom-made materials like terra cotta,” Perry said.

“Commercial craftsman is about finding a way to make simple and inexpensive construction look like more than it is,” Perry said. “This is a time when commercial building is trying to simplify. It’s [style is] achieved with a monolithic material like brick. It didn’t require applied features, but it looks like they’re applied.”

Perry said the Puritan would likely be listed on the National Register if it were nominated, despite changes to its first floor storefront.

Inside the bunker

Behind that two-story volume is what we’ll call the bunker—the area where the cleaning plant operated. This back portion is distinctly industrial with brick walls and concrete ceilings. It’s easy to see how the space might have been divided years ago into ironing rooms, steam rooms, and stitching rooms, but today the space is wide open.

One particular design element are plentiful skylights that allow natural light to pour into the space through the concrete ceiling. There were no electrical lights shining the day of this tour and the space was still brightly lit. The textured concrete ceiling, of both board form and pan form concrete, also provided sculptural relief to an otherwise utilitarian space.

Second space

Around the corner on Second Street, there’s even more potential for growth. Built much later, probably sometime in the late 1930s or early ’40s, a one-story commercial building at 914 South Second doesn’t look like much today, but it contains about 4,000 square feet of space that could bring a much-needed shop or two to the neighborhood.

According to news clippings from around 1938, used cars were sold from the address, which may have been a house, an empty lot, or the building we see today. The structure was likely built as an office and repair shop, and it operated as such throughout the 1950s.

An advertisement from 1953 shows the space operated as Nation Wide Sewing Machine Stores, selling and repairing machines. By the end of that year, however, that company had moved on and the building’s 4,000 square feet were listed for lease in the paper.

The building features an asymmetrical facade arrangement (check out the weird parapet arrangement above) that was described as two-thirds air conditioned offices and one third repair space. A brick support wall still delineates the space today.

After the sewing machine company packed up, several ads dated throughout 1954 show that Maury’s Fluorescent & Appliance Service was located at the address, selling everything from air conditioning units to fuses to electric razors. Maury’s operated at the site until February 1961 when it moved to a larger space around the corner still standing at 962 South Third Street.

By the 1960s, the site appears to be selling used cars and tractors once again, this time for the Summers-Herrmann dealership. By 1967, news clippings show 914 South Second as part of Puritan Cleaners & Laundry, where it remained for decades to come.

Finding a use

So what are SoBro’s most pressing retail needs? We’ve created a couple mock-ups of both the Breckinridge and Second street facades to help imagine what each building could look like with a little fixing up, but these are by no means the highest and best use of the spaces.

Share your thoughts for what you’d like to see fill the Puritan Uniform Rental buildings in the comments below.

With those giant floor to ceiling windows the second floor of the Puritan building would make an amazing studio space…

Or some sort of student activities building.

Is the green storefront Carrara or other? If it is it should be salvaged. I haven’t looked at it up close……. Unlimited potential here. A location for their School of Art.

A Spalding-operated cafe that would be open to the neighborhood would be nice.

such a handsome building. How could this Not be the anchor for a rebuilt row and streetscape? How?

I loved the tour of the interiors that you offered us through photos and knowledgeable text description. This article allowed me a glimmer of hope for some preservation action on these properties. The two other, related recent articles about Spalding’s heavy hand with demo in SoBro seems more pedictive of what will probably happen at 2nd & Breck. Thank you Broken Sidewalk.