By now, what happened at Mall St. Matthews on Saturday, December 26 is old news. Then, what appears to be a group of foolish teenagers caught up in juvenile pranks was taken to the level of mindless absurdity when put in the hands of click-hungry local media. Labeled “riots” with wildly varying crowd estimates of hundreds up to 2,000 youths and presented in a manner that inflamed panic, coverage of the short-lived event was even lambasted by Louisville Mayor Greg Fischer.

Video | Police close St. Matthews Mall early after fights https://t.co/OXxMII26yH pic.twitter.com/VgPHyv2tSH

— CJVideo (@Video_CJ) December 27, 2015

“It was sensationalized by the media, frankly,” Mayor Fischer told WDRB. “Nobody was hurt. Nobody stole anything. There was no damage to the property. I regret that any incident happened, but for the media to blow it up like the world’s coming to an end at the mall, I think is reflective of what we see in this 24-7 media cycle that we’re in right now.”

The St. Matthews Police Department seized the opportunity to soapbox about a crime wave sweeping the neighborhood without providing supporting data to media. As the community struggled to understand what happened in the media confusion, St. Matthews authority figures including its mayor were quick to point fingers at teens, social media, and modern culture.

But this isn’t the first, nor will it be the last, time youth culture has spawned sensational headlines and over-reaction from police. Remember back to November 1956 when Elvis Presley was in town to play a concert at the Louisville Armory on Muhammad Ali Boulevard, then Walnut Street. Police Chief Carl Heustis instituted Louisville’s famous “wiggle ban” after it was believed teenagers would lose control and riot before or after the concert. Just a couple months before, teens had “rioted” at Elvis’ homecoming concert in Tupelo, Mississippi.

For more on how the modern event played out and how the media got caught up in sensationalizing it, check out Laura Ellis’s analysis at WFPL, Joe Dunman’s insightful commentary at Insider Louisville, and a teen’s view of the incident who was at the mall as it transpired.

But what those events highlight is that shopping malls like Mall St. Matthews are not public spaces at all. They’re bear no relation to a city street or a town square despite their appearances. And you have no guarantee of rights when you spend time there.

Black Lives Matter protest disrupts Mall of America, MSP airport https://t.co/vnFEyt6eUC pic.twitter.com/Qix2P1eEJZ

— Brainerd Dispatch (@brd_dispatch) December 23, 2015

Take, for instance, another recent headline-grabbing event just outside Minneapolis at the Mall of America, the nation’s largest with almost eight million square feet under its roof (for comparison, Chicago’s Sear’s Tower is less than five million square feet). On December 23, 2015, a Black Lives Matter protest was scheduled to take place at the mall, organized on social media, before police in swat gear put the mall on lockdown and forced everyone out.

More than the rowdy youths in Louisville, that protest—an attempt to exercise the First Amendment’s right to free speech—highlights one of the most significant shortcomings of this suburban utopia. The shopping mall is not public space. Rather, it’s designed and operated for the single purpose of commerce ruled over peremptorily by a private property owner. Every detail of the modern shopping mall experience has been labored over and scrutinized by teams of experts, architects, and marketing professionals to encourage you to buy something new.

That’s not the original intention of the mall, though. Sixty years ago, shopping malls were intended to be civic places—the new suburban town square. But somewhere along the way, we lost that vision and profit took over. While malls often have elements that make them appear like they’re public plazas connected by idyllic pedestrian streets, these centers are nothing more than the wolves in sheep’s clothing of urban built form.

As pointed out by Alleen Brown in The Intercept’s reporting on the Mall of America incident, the Supreme Court sides with the property owners at shopping malls in cases of civil liberties. Brown describes a 1972 court ruling:

In Lloyd Corp., Ltd. v. Tanner, the Supreme Court decided that Vietnam War protesters in Portland, Oregon could not hand out literature on the interior of this “relatively new concept in shopping center design… sometimes referred to as the ‘Mall.’” The court said that the private nature of a business “does not change by virtue of being large or clustered with other stores in a modern shopping center.”

States, however, may still decide individually that malls in their jurisdiction should allow political speech. A handful of states, including California, New Jersey, Colorado, and Massachusetts, have compelled malls to do so, at least to some extent, but more than a dozen others, including Minnesota, have held that malls are private spaces free to prevent such speech.

But this murky concept of public space at the mall has been evolving for the past sixty years, since the first shopping mall opened in Edina, Minnesota. To understand how the concept of the mall has changed over the years, it’s important to know where the shopping mall came from in the first place and just how radical a transformation it represented for mid-century American culture.

Mall St. Matthews began its life in March 1962 when it opened as, simply, The Mall. The facility was the first indoor shopping center in Kentucky—and it blew people away. The typology that would come to define suburbia had just hit the Louisville scene, six years after the nation’s first mall, the Southdale Center, opened in Edina, Minnesota, in 1956.

On its first day, some 38,000 Louisvillians still chilled by winter crowded through its doors into “Eight Acres of Springtime,” as the Courier-Journal described it. That number shattered the 25,000 person estimated first day crowd. There’s no doubt that the late-winter opening added to the mystique of The Mall’s constant 70 degree, 50 percent humidity interior.

The shopping mall concept was the progeny of Viennese architect and planner Victor Gruen. It represented an attempt to bring the glamour of his native Viennese shopping streets into the modern era in a booming country.

In designing the mall, Gruen sought a pedestrian refuge from the car-clogged streets of cities. “Their [the car’s] threat to human life and health is just as great as the exposed sewer,” Gruen is often quoted. He envisioned the mall as a complete town, with schools, hospitals, and even housing.

The mall never quite amounted to the complete city of the future Gruen envisioned. Instead, it was hijacked by the pursuit of capitalism and became strictly a place for shopping in an ever sprawling suburbia. That’s not to say the mall wasn’t (and in many places, still is) wildly popular. Hanging out at the mall, for many Americans, quickly became a weekend ritual, and these shopping centers drew crowds from cities and rural hinterlands to their bright lights and controlled experience.

Years later after witnessing the exponential increase in car use his designs fostered and their impact on the built environment, Gruen came to disown the mall. “I am often called the father of the shopping mall,” Gruen said two decades after his Southdale Center opened. “I would like to take this opportunity to disclaim paternity once and for all. I refuse to pay alimony to those bastard developments. They destroyed our cities.” Gruen had lost a grip on his concept of utopia as it spread like wildfire across the American landscape.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/204125179″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

In Louisville, no one had seen anything like The Mall in 1962. Strip malls had popped up here and there, but they paled in comparison to Fourth Street’s department stores and big city appeal. But downtown’s streets were clogged with cars spewing exhaust into an already polluted cityscape, and cultural shifts after World War II sought to throw off the heavy architecture of the 19th century for something more “Atomic” and modern. The mall provided for that in a big way, even ensnaring Louisville’s most noted urbanist Grady Clay with its climate-controlled, car-free halls.

“The Mall inside is as superbly inviting as a domesticated world’s fair,” wrote Clay of the structure designed by Rogers, Taliaferro, Kostritsky & Lamp Architects of Baltimore. “It is clearly this region’s closest approach to a shopper’s dream. If the planners and merchants for American downtown districts cannot find useful lessons here, they are incapable of learning… This is merchandising of a quality never seen before in this region.”

Clay went on to criticize the project’s exterior as a “hastily put together factory,” adding that “The Mall from a distance seems just another piece of the interchange.” But he was clearly enamored with the state’s first indoor shopping experience. Remarking on the original mall’s climate controlled interior (with HVAC systems capable of tending 450 homes), Clay described center as “Hawaii at its best.” In fact, over 2,000 tropical plants had been shipped in from Florida for its gardens by Raleigh landscape architect Lewis Clarke.

Notably, local press was particularly infatuated with the notion that there would be no doors to open when crossing from the mall’s lavish corridors into the dozens of retail stores. “Shopping-Mall Doors (Oops! No Doors) Open” declared a bold headline in the March 21, 1962 Courier-Journal. This door-free policy was part of the carefully scripted mall shopping experience. The thinking goes that the fewer obstacles—like a door—between a consumer and the goods he or she might potentially buy, the higher the sales.

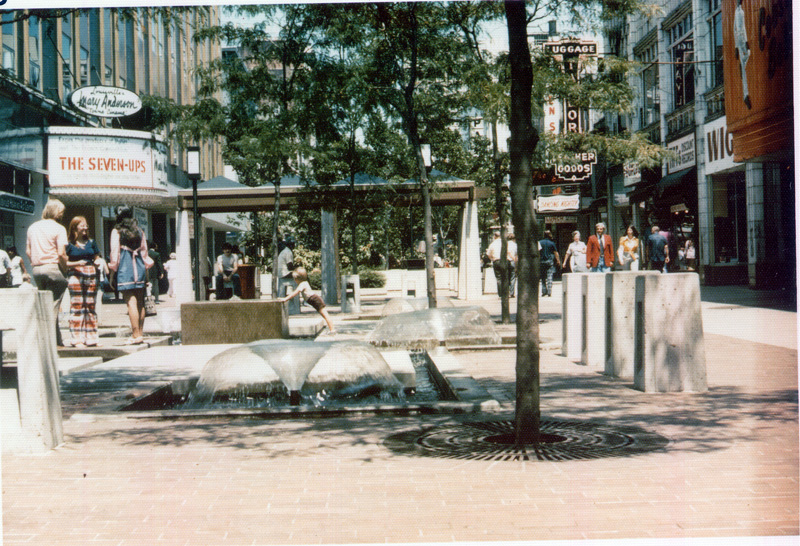

The Mall made suburban living suddenly very glamorous, and it’s easy to see how city planners of the time scrambled to make downtowns across the country just like the modern mall. Louisville’s Fourth Street was, for a time, converted into a lushly planted pedestrian mall, complete with gaudy waterfalls and chintzy lighting making the strip’s historic architecture look all the more foreign. Many facades were covered up or substantially modified to fit the streamlined mall aesthetic. Worse, block upon block of Third and Fifth streets were razed to create parking for suburbanites to drive in for downtown shopping.

But making downtown into a mall fell flat on its face, failing spectacularly in city after city. It turns out that the city and the suburb are two very different places, and to turn the former into the latter would have required complete redevelopment. And nothing beats the parking capacity of the suburban landscape. Even Clay noted about The Mall, “Functionally, the outside seems to work well. In three recent trips during crowded hours, the writer had no difficulty getting off the highway, parking, or leaving.” The era of car convenience was in full swing.

“What was 67 acres of open field is now…a virtual young town—complete with a community hall,” the Courier-Journal wrote upon The Mall’s opening. “Behind the light-cream brick of the outside is the equivalent of five city blocks of stores.” The original retail line-up must have resembled something of a city street as well, with a shoe repair shop, a bank, a flower shop, a drugstore, a dry cleaners, a grocery store, and even a cocktail lounge in the mix. Improving on the city, the article also noted that, inside, “there are no cars to dodge… giving shoppers complete safety when they enter the center proper.”

Yet while Mall St. Matthews was designed with a number of nodes that resemble mini-town squares, there is nothing public or civic about the spaces. It’s all just a ruse to get you inside to open your pocketbook. The original mall featured tropical gardens with fountains and benches, an aviary of imported birds, a playground for children, and an oversized chess set, still a familiar sight today.

Recognizing its place as a center in the centerless suburban landscape, The Mall did open with some semblance of civic ambition. The facility contained a 300-seat Community Hall and a meeting room available for public use with a cleanup fee for nonprofits and a rental fee for others.

If you're from Louisville, you've probably seen one of our most popular projects: the chess set at Mall St. Matthews. pic.twitter.com/ECh1qW4jvD

— Louisville Lumber (@LouLumber) May 18, 2015

Over the years, the mall has swelled to over a million square feet—that’s a hair under 23 acres. And it still remains just as popular today as when it opened, even though modern views of convenience are changing the way we look at suburban infrastructure.

One other critical reason Mall St. Matthews is still relevant in Louisville today is that, to some degree, it still fulfills a basic social role in providing what’s been termed by author and urban sociologist Ray Oldenburg as the “Third Place.” He coined the term in his important book, The Great Good Place, meaning somewhere not quite public yet not quite private, either.

“Third places are nothing more than informal public gathering places,” Ray Oldenburg has said. “The phrase ‘third places’ derives from considering our homes to be the ‘first’ places in our lives, and our work places the ‘second.’” For Oldenburg, we need a place to get away from our regimented lives and branch out from our closest relationships of family and coworkers.

A coffee shop or a local bar, where we’re among our neighbors, fit the bill quite well. They form their own sort of community that makes a city a stronger, healthier, more interesting place. But in suburbia, these places can be exceedingly rare. For many, the shopping mall has become the substitute. But, as Oldenburg says, the mall is too regionally (or in the case of Mall St. Matthews, “Super-Regionally”) focused to provide a fulfilling community environment and real Third Place.

“Totally unlike Main Street, the shopping mall is populated by strangers. As people circulate about in the constant, monotonous flow of mall pedestrian traffic, their eyes do not cast about for familiar faces, for the chance of seeing one is small. That is not part of what one expects there. The reason is simple. The mall is centrally located to serve the multitudes from a number of outlying developments within its region. There is little acquaintance between these developments and not much more within them. Most of them lack focal points or core settings and, as a result, people are not widely known to one another, even in their own neighborhoods, and their neighborhood is only a minority portion of the mall’s clientele.”

So in the end, the mall occupies a precarious position in the built environment. We treat it as public when it’s actually very private space. And as such, the private property owner is king of the castle, as demonstrated by new policies banning unescorted minors from the mall following the December 26 incident.

In the fallout from that event, Mall St. Matthews, today owned by mega-mall-operator General Growth Properties (GGP), has instituted a policy of barring minors from the facility without an escort over the age of 21 during certain times of day. Security has been checking IDs of those who appear young and turning away those below age 17. Minors who work at the mall’s 130 retail stores are required to wear wristbands labeling them as employees. The move has also spurred some to propose increased enforcement of a youth curfew citywide.

While this new policy is billed as temporary, mall management has remained silent on how long it might be in effect. And the economic impact on the mall’s stores remains uncertain. On the GGP’s website, the company boasts that 38 percent of shoppers are between the ages of 14 and 24 with combined $30 million in sales at the mall.

While the mall still maintains its stranglehold on retail in Louisville, trends are shifting back toward something more traditionally public. Wave after wave of development in the core of the city is making retail viable again in Downtown and surrounding core neighborhoods. And the mall itself is changing. In Louisville, those changes look like the Summit shopping center or the open-air outlet mall just outside town, but in other places it looks like a complete street, with mixed-use buildings nestled up to a roadway.

With these new forms, we’ll likely continue to grapple with what’s public, what looks public, and what’s not public at all, but it’s an important discussion to be had. Public space has been at the core of American life from the very beginning, and we still come together as a community in town squares across the city for special events and important civic occasions.

But while true public space grants us the freedoms we’re guaranteed in the Constitution and represent the heart of what makes a place civic, it also comes with grit and conflict that might startle or upset some accustomed to the carefully choreographed and whitewashed landscape of the mall.

We’d hope Louisville wouldn’t give up the excitement of Bardstown Road or the beauty of West Main Street to fool itself into a comfortable mirage. Let’s celebrate our public spaces and, like Victor Gruen, recognize that the mall didn’t live up to its grand expectations.

How ironic that free speech and association are excluded from the places where the public gathers in throngs to buy the fruits of capitalism. Seems like business wants freedom from regulation where it exploits underpaid workers, but wants the Constitution put on hold in its fantasy boutiques. The Malls basically ruined the Middle Fork of Beargrass Creek. All of the road salt runoff, lawn chemicals and automotive drippings from the 67 impervious acres were directed into the stream. Since the 60s, chronic high flows and chemical laden runoff have scoured and poisoned the creek. Its a washed out eroded ditch now where gluts of woody debris are covered with blowing plastic bags, soda bottles and cigarette butts. One of Louisville’s original natural features that was home to the first Louisville European settlers is now a road drain. But as long as one can get into an air conditioned car and get out in a nice parking lot, no one notices.