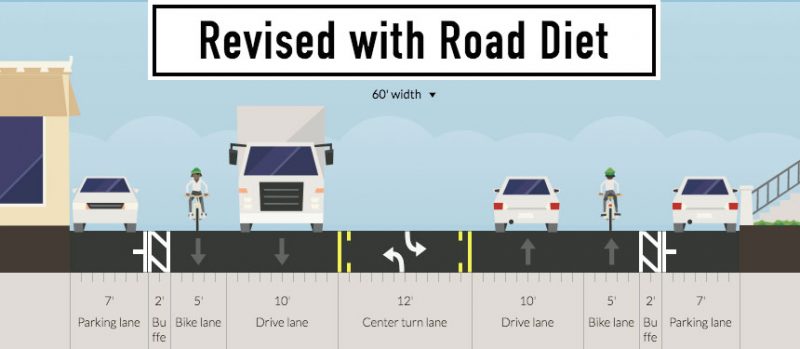

Below are two roads—both 60 feet wide. The top design does one thing incredibly well: it moves cars efficiently in a straight line. The next one, below, does this and many other things as well.

This is because motorists do not drive only in straight lines—the “revised” layout includes a dedicated turning lane to prevent congestion. The resulting configuration slows traffic speeds with narrower driving lanes. There’s space for bikes. Parking lanes are right-sized—not nine feet wide but seven feet, with a two-foot buffer zone. With everything compartmentalized just so, traffic moves more efficiently, even with one less driving lane.

And what’s maybe less obvious is that this road is safer for pedestrians too: slower, more predictable traffic movements make it easier and safer to cross the street.

That “revised” street section is called a road diet. Among traffic engineers and city planners, the safety benefits of such a street design are well-known and well-understood. The debate over their usefulness is over and their benefits are clear.

How about more like this in Louisville?

So why doesn’t Louisville have more of these road diet configurations? One of Louisville’s public works employees told me he has a list of twenty or so city roads he’d like to see get a road diet. And yet in Louisville, we have no dedicated funding source for projects like this.

In the city budgets of the last three years, there has been funding for sidewalk improvements, for bike lanes, and for road repaving—all the ingredients needed for a complete street. But all that money is in separate pots, all going to separate projects. We’ve got the ingredients we need, but no recipe to follow to make a better street. We don’t provide any funding for the holistic approaches that make the street safer for everyone. This needs to change.

In Louisville, we have an 8-year-old, 160-page document that’s gathering dust and the promise of a multi-modal plan that’s more than a year overdue. What we don’t have is a strategy or funding source for implementing complete streets. Instead, we come by our most people-friendly streets somewhat haphazardly.

Sometimes “bike money” is used for these projects—as on Grinstead Drive in Crescent Hill. Sometimes “repaving money” will get used—as is the case in an upcoming project on Third Street in Beechmont. In both cases, a four lane road was “dieted” down to three. Considering that these projects affect all road users, their implementation should be more than an afterthought. Their funding mechanism must be more clearly defined.

A “complete street” isn’t one specific thing.

The term “complete street” is a general way to describe roads designed with all users in mind: people in cars, people riding transit, people walking, people on bikes. A street becomes “complete” when it is designed for people, not for quickly moving cars through a space.

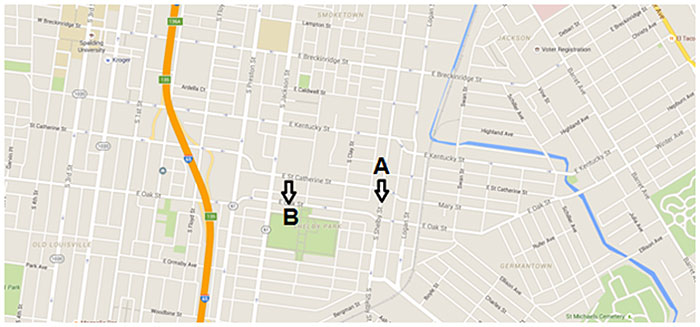

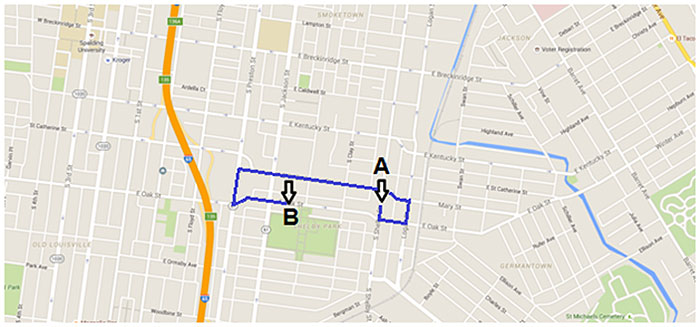

Here’s another example of what a complete street can be. Take this network of one-way streets in Shelby Park and plot your route from Point A to Point B.

The network above was designed for getting cars to and from downtown as quickly as possible. If you time the lights right on Oak Street, for example, you can get from Old Louisville to the Highlands without ever hitting the brakes, moving along at 30 or 40 miles an hour. This is great for motorists on their rush hour weekday commute, but bad for virtually everyone else every other time of the day. If you’re a resident, it makes your roads a maze to navigate—annoying and inconvenient. If you’re a kid playing in Shelby Park, it makes chasing a ball into Jackson or Oak streets potentially life-threatening.

Simply “two-waying” this grid would benefit everyone—in ways that go beyond safety. It’s important to remember here that streets are more than just places for people to get from Point A to Point B, they’re also the social and economic engines of our cities. Creating a two-way grid would increase property value and drive down abandoned property rates. It would enhance local business. Walkability would increase and speeds would settle to a safer level.

The advantages of two-waying, like the advantages of road diets, are well-known and well-understood. Both are examples of complete streets. Both benefit their surrounding communities.

And, unfortunately, both suffer from a lack of a dedicated funding source from Louisville Metro government.

What gives?

It’s not so much that this lack of a funding mechanism is disappointing as it is surprising. So many people in local government “get it”—from Metro Council members who clamor for road diets and two-way streets, to Public Works and Planning employees who can rattle off the benefits of these kinds of projects. Many times, Mayor Greg Fischer has spoken of the need for making our city’s streets more people friendly—it is literally the first goal in his strategic plan. And, yet again, there is no specific funding for these kinds of projects.

Why is this important? Here’s just one example: Metro Louisville Public Works is currently considering a redesign for Jefferson Street through Downtown. Their design features bus islands, a protected bike lane, and curb extensions for pedestrians. Four driving lanes would be taken down to three. These are all great things—design concepts that benefit all users.

But there’s one big problem. There’s no money for a project like this. To be sure, there is money in a city budget of hundreds of millions of dollars. For instance, “bike money” could pay for this project—but at the cost of 75 percent of its annual allotment on a bike lane that goes 0.9 miles and for which the vast majority of the project cost is not related to a bike lane. There is money available, just not money for this complete street project.

This is a problem.

And it’s a problem my organization, Bicycling for Louisville, is aiming to address. In the past, our mission has been to make streets safe and accessible to people on bicycles. Moving forward, our mission is expanding to advocate for better streets for everyone—to jumpstart more complete streets in Louisville.

Our new advocacy initiative, Streets for People, will be an attempt to change the way we look at our roadways. We want them to be seen as not just arteries for moving cars efficiently, but as public spaces that consider the safety and needs of all their users—neighborhood residents, commuting drivers, local drivers, pedestrians, transit users, and yes, bikers.

Our first goal is to see a funding mechanism for holistic roadway redesign implemented. Until that happens, this effort toward multi-modal street design will be staggered and piecemeal—a little here, a little there, none of it coordinated. If this truly is the number one goal for our city, let’s allocate some money for it. That seems like a simple first step.

[Top photo of Vanderbilt Avenue in Brooklyn courtesy the New York City Department of Transportation / Flickr.]

The one way streets through shelby park and smoketown always have seemed racist and classist: The neighborhoods’ residents’ quality of life is undeniably and directly being sacrificed for wealthy white people’s convenience. But making it two way and road diet will just push people out as property values rise…

I always find it is unfortunate to have someone that clearly has no background in Civil Engineering of Environmental Engineering writing articles about something clearly out of their element. Anyone with any understanding of one and two-way streets knows that one way streets are considerably safer. And, yes, you can find anecdotal articles written by people that are not engineers or versed in research arguing the contrary with non-causal data. But read any peer-reviewed engineering article and you’ll be hard pressed to find an argument the other way.

But safety is but one factor to consider.

Consider the determent to the environment, the urban heat island. Moving the public out of an urban setting and into the suburban setting faster actually decreases pollutants in the urban core, much, I’m sure, to the chagrin of Suzanne Whiston who can clearly find no winners. Moving those cars more quickly through the neighborhoods decreases the pollutants released into the air in those areas. It is the same reason the interstates are so proximal and that streets, such as Bardstown Road, have lights that are designed to move people out of the urban core. Perhaps she would prefer that we decrease the health of those inhabitants by slowing cars and decreasing the air quality in those areas. And I’m sure if that happened we would simply have something else to argue about.

The Mayor and the politicians in Louisville would prefer to see a downtown that is revitalized, or vital in any respect. An easy way to do such a thing is to make the downtown area less auto-centric. Make the area seem more friendly to the users. Making the streets two-way would certainly help with that goal, it has helped in Vancouver, in Charlotte, and in several other cites around the globe. Making the streets safer to walk along, safer to ride upon, safer to drive upon, would make the urban core as a whole, more usable instead of a ghost town every evening and weekend.

To do such a thing, streets need to be changed. I’m not sure that complaining about where the money is coming from is going to solve the problem. Perhaps we pool our money, like the republican council people do to get more city streets paved, in order to actually break some ground and get the city moving in a positive direction. Instead of standing in the way of progress I suggest we embrace the progress that can be made and allow it to stand as an example of how things should and could be done.

There has to be an understanding that TARC has a major hurdle associated with moving people as well as keeping them safe. Coming up with a plan that TARC can be supportive of by meeting their needs as well as creating safer bike routes, safer driving lanes, safer bus stops, safer sidewalks, is definitely a win-win all the way around.

@Jacob: 2 way streets are safer: http://www.streetsblog.org/2007/03/22/transportation-planner-one-ways-hurt-more-kids/

@Jacob: And your notion that moving more cars through the city at a faster pace is an environmental benefit is simply absurd.