The last several years of local politics in Louisville have seen a dramatic increase in the attention paid to the West End. From the cover story on Louisville Magazine’s March 2013 issue imploring us to “Stop Ignoring the West End” to the recent controversy around the development of a Walmart at 18th Street and Broadway and practically a million other things in-between, western Louisville has rarely, if ever, been more central to debates about the future of the city.

This has been especially true of Mayor Greg Fischer’s campaign to address the number of vacant properties in the city, a problem that has itself become almost synonymous with the West End.

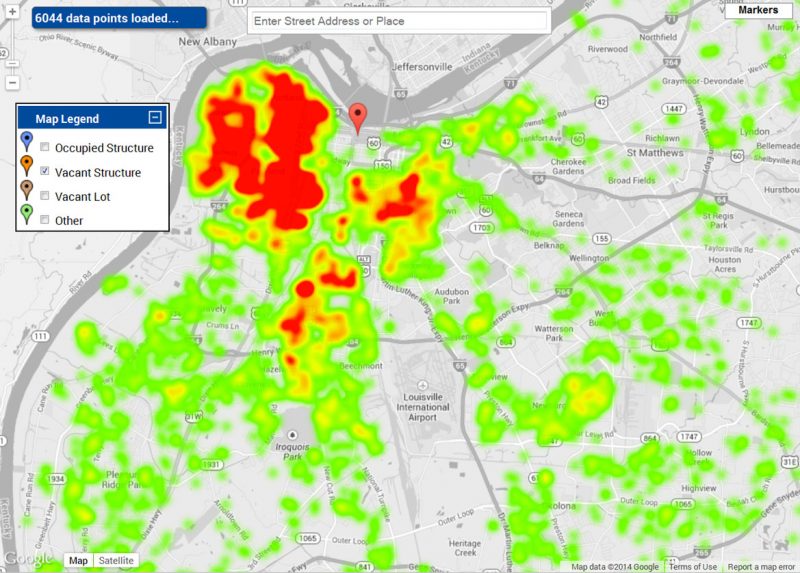

But in asking the question “where are Louisville’s vacant properties?” we’re doing ourselves a disservice if we think of this issue as being simply a “West End problem.” Were you to go looking around the internet for a map of Louisville’s vacant properties to answer this question, you’d most likely stumble across the one below, from Metro Louisville.

The map is interactive, letting the user switch between a view of individually plotted vacant properties and a “heatmap” view, which produces a visually concise summary of the geography of vacancy in the city. Glancing at the map, it becomes clear that, while the West End isn’t the only place in the city with vacant properties, the problem is acutely concentrated west of Ninth Street.

Setting aside the fact that data on vacant properties can be fuzzy and inaccurate, we can say with some certainty that between half and two-thirds of the city’s vacant properties are located in the West End. Back in 2012, the Metropolitan Housing Coalition even estimated that up to 30 percent of all properties in some West End neighborhoods were vacant, only further highlighting how the West End is disproportionately affected by the city’s vacant properties problem.

My argument, however, is that the data we use to help us understand the nature of the vacant properties problem is limited in its understanding of geography, which in turn limits the scope of our imaginations when it comes to how we might address the root causes of this problem.

In the city’s official data, each vacant property is represented by a single address, which is then geocoded—or turned into a corresponding pair of latitude and longitude coordinates—and plotted on a map.

But no vacant property is an island. Each one is bound up in processes that stretch far back in time and far beyond the boundaries of the individual parcel. The challenge is how to represent these alternative geographies and use them to inform how we think about the problem of vacant properties and the ways we might go about solving it.

No vacant property is an island. Each one is bound up in processes that stretch far back in time and far beyond the boundaries of the individual parcel.

The answer, crucially, still hinges on data. Even though the city’s official database represents vacant properties as only a single point, other, less-visible data provided by the city allow for another layer to be added to the ways we can represent the geography of vacant properties.

Using data from the Department of Codes & Regulations on vacant properties that have required maintenance from the city, we can map not only the location of the vacant properties themselves, but also the location of the (last known) owner of the property.

This results in a visual representation of the hidden connections between places that are often ignored in conventional geographic representations of vacant properties.

Simply drawing a straight line from a vacant property to the location of its owner allows for an alternative understanding of where vacant properties are, and, in turn, how we might go about confronting the problems they present to our communities.

Louisville’s vacant properties aren’t just in the West End—or even in places like Smoketown. They’re also in St. Matthews and Middletown. And in Dallas, Washington, D.C., and Oklahoma City.

There’s little overlap between the vacant property addresses and the contact addresses in the database, suggesting that many of the owners of these properties were never living in them. While each individual property might represent a unique set of circumstances, these owners range from absentee slumlords, big banks in possession of dozens of foreclosed homes, and even individuals who have gotten stuck with a property after the death of a family member.

What this means, ultimately, is that significant numbers of properties—in the West End or elsewhere—are currently owned by outsiders and left to deteriorate, knowingly or unknowingly, with those in close proximity to these properties left to deal with the mess.

At the scale of the city, one can see the lines emanating from the yellow dots representing vacant properties in the West End to the orange dots representing the property owners in other parts of the city.

Indeed, the density of property flows emanating from the West End outward makes it difficult to discern the direction of each relationship. According to this dataset, there are 3,634 vacant properties (or 54 percent of the citywide total) within the West End. But only 1,417 contact addresses (just 21 percent) are within the West End, suggesting a significant level of absentee ownership of property in the area.

But this problem of absentee ownership can also be seen citywide. Of the more than 6,700 vacant properties in the dataset as of early February 2015, roughly 20 percent had listed contact addresses outside of Metro Louisville.

The highest single concentration outside of the city is in the Dallas, Texas metropolitan area, where 95 properties are owned by the likes of Fannie Mae and a host of banks (including Bank of America and the Bank of New York Mellon) that share the same address in Plano. Addresses in Washington, D.C. are listed for 45 properties, mostly belonging to Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac. Nearly all of the properties owned in Oklahoma City are registered to either the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development or Pyramid Real Estate, a company responsible for managing previously foreclosed properties now under the ownership of the federal government. Further down the list, cities like Lexington, Chicago, and Atlanta are also home to a large number of Louisville’s vacant property owners.

These maps are, ultimately, more art than science. And like any dataset, there are a million ways to slice this data that might result in a different kind of picture. But these visualizations are meant simply to emphasize the fact that no vacant property exists in isolation, just as the West End doesn’t exist in isolation from the rest of Louisville.

Instead, these properties and neighborhoods are connected quite closely to places near and far through flows of money and property ownership that dictate the shape of our built environment. But failing to recognize that the problems facing the West End—like similar areas in cities across the US—have been created and shaped by outsiders implicitly places the blame for such problems on the people that live in these neighborhoods.

So if the city of Louisville is serious about fixing the problem of vacant properties in the West End, it’s important that we understand just how interconnected the West End is with other places, whether they be on the other side of downtown or the other side of the country. The more we see vacant properties in the West End as fundamentally separate and apart from the rest of the city, the more likely our proposed solutions will only end up exacerbating these problems.

[Top image: A vacant property at East Breckinridge & South Hancock, Louisville. Photo by Diane Deaton Street / Flickr.]

A GREAT READ ON THE BLIGHTED CONNECTION OF VACANT PROPERTIES:

As I and other local community advocates have made claim, the West Louisville vacant and blighted property problem is not the result of the lack of care and interest of local residents but is the result of individuals and entities outside the neighborhoods (i.e., slum-owners, predatory investors, banks, and distance family members).

The Chickasaw neighborhood once thought to demonstrate this through protest by identifying owners of area blighted properties that lived in more “affluent” areas of the city and state. It was hoped that they would be encouraged to maintain these properties or otherwise be humiliated by their property neglect.

However, before Chickasaw could target its most problem properties the city assisted the private owner to transfer ownership by donating the properties to a local church, knowing that small church could not afford to maintain the large properties. Now the neighborhood has had to battle with one of its faith-based institutions on rehabbing or demolishing the properties and the many problems it brings.

The photos you used are great illustrations of abandoned structures – just thought you’d want to know that the two brick shotguns on Rowan Street were demolished 5 years ago, and the two-story brick house on S. 23rd was demolished just last February.

One thing I’d like to have seen you address is the difficultly in clearing title on abandoned properties whose last owner of record is deceased. It’s a knotty problem, and solving it will require more resources than the city is prepared to commit, I think.

The only way to clear title in many of these cases is for the city itself to take title – as noted, when the property owner is deceased and no family is interested, the situation isn’t going to suddenly improve – the ONLY way to deal with it is for the city to take the property before it becomes so deteriorated that it can’t be salvaged.

We’ve been talking eminent domain or similar for a very long time. If I had a dollar for every politico-program invented to negate the endless bleed I would have enough money to rehab a city block. Even in the city’s preservation districts the evident deterioration is disturbingly cancerous. Limerick and Old Louisville show serious lack of oversight for buildings supposedly held to a higher standard. I have never seen the 1300 block of South Floyd look so frightening. I once envisioned Floyd Street as the connector corridor to the medical center. Yet the street is lined with disinvestment and a boutique hotel whose owner flattened all of the residential structures nearby for unlandscaped surface parking. This article points rightly to the depth of the problem from without. And I so had Clark on my radar for post grad work!

Metro is full of stats and cutesy dept names but woefully lacking in people who understand this issue from the street . Those of us who do have the cred are never asked. And I still have my eye on a house in Parkland vacant ten years in a family trust with no live trustees…..!

Nice Taylor!

The city should be landbanking these properties much sooner. Everyone is wanting a piece of the pie in the west end when/if the promise zone application comes through and funding is funneled to there.

Great work, Taylor, the connections peeled away by your article has helped me understand what I am up against in my attempts to find a Portland site for a wished-for urban market farm that I’d like to found. I need a minimally habitable

…building with 2 vacant lots.