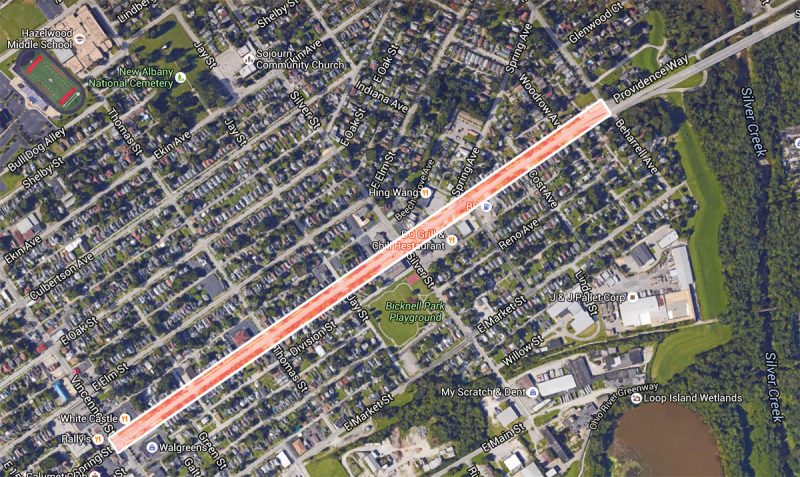

Construction has begun on a road diet project along New Albany‘s Spring Street. The redesign covers an eight-block, .8-mile stretch of Spring between Vincennes Street and Beharrell Avenue.

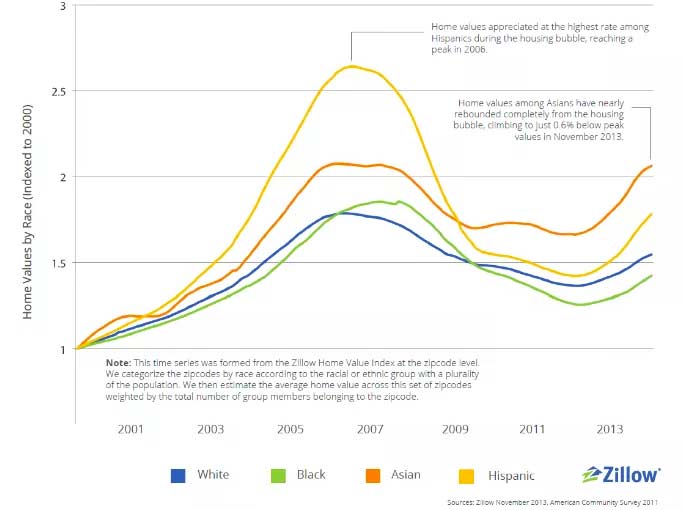

The project goals include increasing user safety and reducing traffic speeds. Spring Street through New Albany here is among the most dangerous corridors in Southern Indiana, according to the Kentuckiana Regional Planning & Development Agency’s (KIPDA) “High Crash Segments” study. Spring from Woodrow Avenue to Silver Street ranked second most crash-ridden while Spring from Silver to Vincennes ranked number 17.

Only two months ago, Chloe Allen was killed by a motorist while walking at Spring and Vincennes streets. Then only weeks later, another motorist struck another pedestrian at the same intersection.

Several years ago, noted urban planner Jeff Speck of Speck & Associates was hired to study New Albany’s overall street grid and make recommendations, including along this stretch of Spring Street. In his December 2014 report, Speck looked at just this corridor, analyzing existing conditions and suggesting improvements.

Spring Street is more than 50 feet wide and, according to Speck’s study, already carries a lot of traffic. The four-lane street sees roughly 23,000 cars daily between Silver and Beharrell, where it transitions into a highway-like Ohio River Scenic Byway. This causes “excessive” traffic speeds, according to Speck, and “treacherous” pedestrian conditions. From Silver to Vincennes, traffic drops significantly to 16,000 to 18,000 vehicles a day, but speeds remain high.

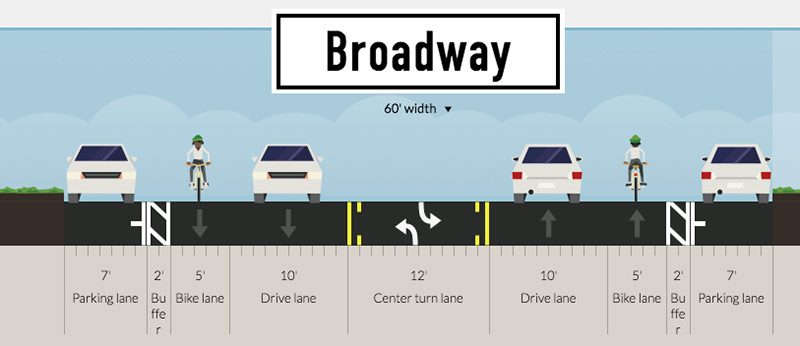

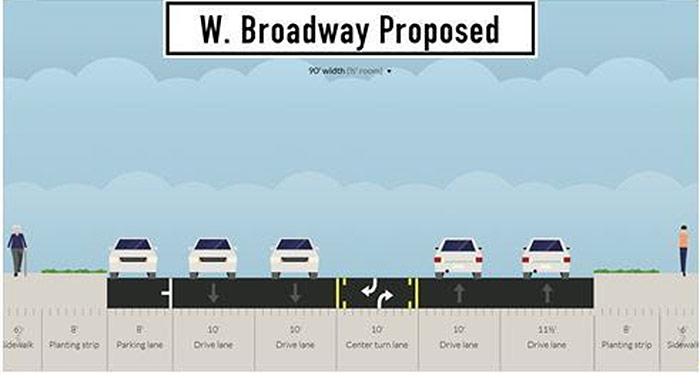

Among his recommendations, Speck called for a 4-to-3 road diet, where a center turning lane is added. “The introduction of a 3-lane configuration will result in a street that is considerably safer,” he wrote. And fortunately, that’s among the changes taking shape in the corridor now.

According to the above rendering of Thomas Street looking west from the City of New Albany, two 11-foot travel lanes flank an 11-foot turn lane. Buffered bike lanes are also planned along the curb here with green paint increasing the visibility of a conflict where motorists and cyclists cross paths. To the west, the bike lane becomes a door-zone lane with the buffer on the wrong side of a row of parallel-parked cars.

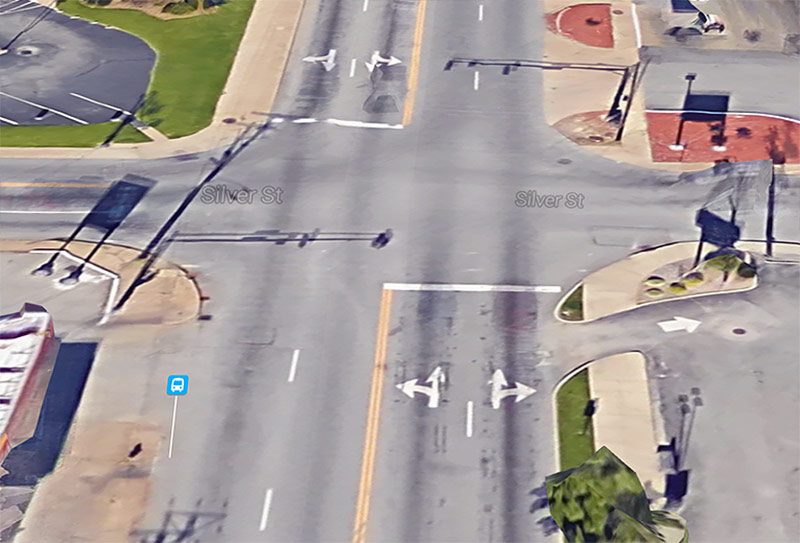

The above rendering shows Spring Street at Silver Street looking east, where a new left-turn lane is being added. “The new signal will also be able to determine if there are longer queue lines for certain lanes, and then adjust the timing of its signal to help get drivers to their destinations quicker,” according to the City of New Albany.

For pedestrians, the project adds ADA-accessible ramps at intersections. Traffic signals will also include walk indicators, but it’s unclear whether they will be automatic or require an pushing a beg button. Speck’s recommendations had called for additional crosswalks with pedestrian refuges built in the turning lanes, but those are not included in the current plan.

Besides these safety improvements, the Spring Street project aims to maintain traffic along the corridor at current levels. “There is a growing concern that New Albany streets will be used as a ‘pass-through’ for those wishing to avoid the toll,” the city writes. The Sherman–Minton Bridge will be the only un-tolled Interstate highway bridge following the Ohio River Bridges Project, and an influx of speeding motorists could eliminate the project’s safety benefits.

The bulk of the $811,000 project was funded with federal grants under the Highway Safety Improvement Program and administered by the Indiana Department of Transportation (INDOT).

Crews began working on the westbound lanes on Monday, July 11 and after about a month will switch to the other side, according to the City of New Albany. The entire project is expected to be complete by October 1.