A local architect has asked Metro Louisville take a close look at a bridge not on anyone’s radar screen: a local access bridge. Steve Wiser believes two new spans similar to the Second Street-Clark Memorial Bridge could help solve Louisville’s near-term traffic needs without the bureaucracy involved with a Federal project like an Interstate bridge.

Connecting to the federal highway system is one of the significant costs and delays to building a bridge. Environmental impact statement bureaucracy, land acquisition complications, federal and state funding restrictions, painstaking planning process, etc., have prolonged our bridge construction.

What if we built a bridge without tying into the interstate system? Why not construct a local-access only bridge? In fact, such a bridge was just completed. It is the new bridge over the McAlpine Lock and Dam that is viewable from I-64. The cost was below $20 million and took less than 4 years.

His proposal suggests a bridge connecting New Albany and Portland and another in Downtown connecting Jeffersonville-Clarksville with Louisville. Based on the cost of the Shippingport Bridge and smaller bridges in other states, Wiser thinks the two spans could be built for around $120 million, less than half the cost of one Interstate bridge. Even if they ended up being more expensive, we see many benefits to having increased capacity on cross-river local roads.

First of all, the connect city grids. Once you are across the bridge, you’re in the city; not a jumble of on- and off-ramps. Second, they promote centralized, urban growth in the areas around the bridges. While Interstate bridges promote sprawl and lower-density forms that require high-speed, low-obstacle personal transportation, a local-access bridge is part of the adjacent city. It serves this immediate area. Most important, though, is the multi-modal aspects of the local-access bridge: everyone can use it. We recently saw the problems of a single street-level bridge at Thunder when walkers and cyclists couldn’t cross the Ohio River when it was closed off. A local access bridge invites people, bikes, and cars to use the same piece of infrastructure equally.

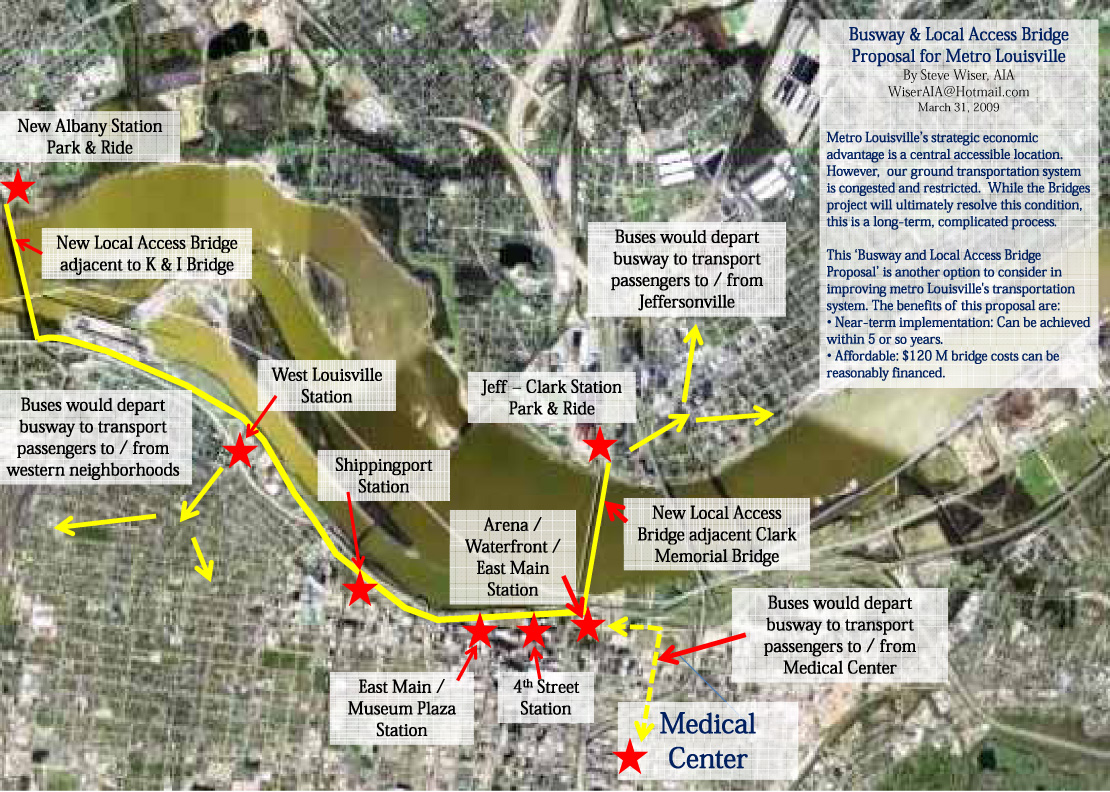

Wiser’s proposal goes even further than connecting the community with bridges. He also brings up the notion of a Bus-Way connecting the two new bridges as a transitional approach to light rail. The plan has similarities to a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system and could potentially be build affordably in existing rights of way.

Louisville’s auto dependence isn’t going away anytime soon. The next generation though is seeking other options, especially after the $5-a-gallon gas-sticker shock last summer. Perhaps we can leverage this dilemma into a major economic development opportunity.

Western Louisville has several desirable characteristics: densely populated; a large percentage of non-car owners; and, a high number of residents who work downtown or at the medical center; in other words, a good demographic base for a rapid transit system.

What if a bus-only roadway were built between downtown and western Louisville, along the waterfront? There would be few obstacles, making it an extremely quick trip. Buses could exit the eastern terminus, dropping off passengers in the medical center or downtown, and then get back on this limited-access roadway for a fast return trip to west Louisville.

We think these ideas deserve serious consideration as Louisville considers its transportation future. Both the local-access bridges and the dedicated bus-way could help to knit together much of the city and provide a more effective and urban-minded approach than an Interstate bridge Downtown. Steve has written much more about his proposal, and you can read them in their entirety below.

Moving Louisville Forward: Near-Term Affordable Traffic Solutions

[ originally written February 26, 2009 by Steve Wiser ]

Breaking News: The Sherman Minton Bridge is closed indefinitely.

Fortunately, this was NOT the headline recently when a barge hit the bridge support on February 5th. The Sherman Minton was only shut down for three hours and our metro area dodged a major disruption. This demonstrates how fragile our transportation infrastructure is.

For a community whose major economic development advantage is a central accessible location, Louisville is at a serious disadvantage when it comes to our ground transportation systems inaccessibility.

Spaghetti Junction is at a standstill most days. Bridges are routinely blocked due to accidents. The recent gas price spike highlighted our limited alternative mass transit options. Construction regularly obstructs downtown streets. River Road west of Sixth Street is indefinitely closed. Commuting times have doubled over the past twenty-five years. And, when the arena opens in two years, Ring Road may be a fond memory compared to the urban gridlock that could result.

The $4 billion dollar Ohio River Bridges project is expected to solve most of this, but when will this be completed? At the current pace, it could take decades. And, how will it be funded? Tolls? That’s certainly not a popular method. Much effort has been expended on this enormous undertaking, and its progress should continue to ultimate implementation. In the interim, though, there has to be some near-term relief for our traffic nightmares.

Other cities haven’t had the trouble we’ve experienced in getting bridges built. Cincinnati has 7 compared to our 3. Nashville has 9, with Pittsburgh 24, and St. Louis 6.

Connecting to the federal highway system is one of the significant costs and delays to building a bridge. Environmental impact statement bureaucracy, land acquisition complications, federal and state funding restrictions, painstaking planning process, etc., have prolonged our bridge construction.

What if we built a bridge without tying into the interstate system? Why not construct a local-access only bridge? In fact, such a bridge was just completed. It is the new bridge over the McAlpine Lock and Dam that is viewable from I-64. The cost was below $20 million and took less than 4 years.

Using this as a prototype, what if we built two local-access bridges: one that parallels the Clark Memorial and connects into First Street; and the other adjacent to the K & I Bridge.

As to the cost, these bridges would be wider and longer than the McAlpine bridge, but let’s say they each cost $60 million, or $120 million total. This could be split affordably between Kentucky and Indiana. West Virginia has built several similar bridges for less than $60 million each.

Separating commuters from cross-state traffic would greatly lessen the stress on both. There are some technical issues, but these are solvable and local-access bridges can be built now.

Next question: what about mass transit? $770 million was the estimated cost seven years ago for a light rail system from the Snyder Freeway to downtown. Today, that price tag is probably closer to $1 billion. While the feasibility of light rail is debated, perhaps there is another transitional approach.

Louisville’s auto dependence isn’t going away anytime soon. The next generation though is seeking other options, especially after the $5-a-gallon gas-sticker shock last summer. Perhaps we can leverage this dilemma into a major economic development opportunity.

Western Louisville has several desirable characteristics: densely populated; a large percentage of non-car owners; and, a high number of residents who work downtown or at the medical center; in other words, a good demographic base for a rapid transit system.

What if a bus-only roadway were built between downtown and western Louisville, along the waterfront? There would be few obstacles, making it an extremely quick trip. Buses could exit the eastern terminus, dropping off passengers in the medical center or downtown, and then get back on this limited-access roadway for a fast return trip to west Louisville.

A former railroad easement already exists to facilitate this construction, and it can be elevated with precast concrete spans to avoid flooding problems. The buses can have a GPS tracking device to allow waiting passengers to monitor the estimated-time-of-arrival at their bus stop, or via their wireless laptop, a very user-friendly incentive.

Park and ride garages could be placed on the Indiana side where these same buses could cross over on the new local-access only bridges.

In addition, it could help alleviate congestion resulting from large crowds at the new Arena, Kentucky Center for the Arts, Actors Theater, Convention Center, Galt House complex, and major downtown events like Thunder.

This busway proposal would be less than three miles in length. The buses would be of a regular design for ease of maintenance and serve other routes when needed. And, they would operate on natural gas.

As to cost, let’s say it may be in the neighborhood of $100 million. How to pay for it? Well, there might be some spare change left over from the federal budget, but let’s don’t count on it. There will be revenue from fares, yet this probably won’t cover most of the expenses.

There is another demographic of western Louisville that could help a funding solution. Housing costs are almost half of the community average. Since the city uses TIFs (tax increment financing) for major public improvements, what if the west Louisville area, which will directly benefit from this system, becomes a TIF district and any property value increases facilitated this construction?

Neither the local-access bridges or busway transit would compete with the massive Ohio River Bridges initiative, but work together in a compatible manner. They will, though, provide an immediate relief valve for our crowded interstates as well as some welcomed economic development spin-offs. And, we won’t have to worry as much if some catastrophe, like a barge collision, shuts down a bridge for an extended period.

Our competitor cities are building innovative, creative transit infrastructure to strengthen their growth and success. It’s past time for Louisville to get moving and implement our own doable alternative transportation solutions.

Let’s not only make Louisville the Number 1 livable city in America, but the most accessible as well!

(Steve Wiser is a local architect and author of the book Louisville 2035 which offers a future vision of the city in 25 years. He can be reached by email at WiserAIA@Hotmail.com or visit his website: www.WiserDesigns.com)