Earlier this week, we took a look at an old editorial from 1955 calling for the bombing of Downtown Louisville to make way for modern development that would accommodate the automobile. It turns out, Louisville did, in a way, bomb itself away in the years after World War II, only in slow motion with a wrecking ball. Today, Downtown’s historic fabric has been decimated, still pocked with parking lots, poorly rebuilt buildings, and, sometimes, quality architecture that we’re lucky to have today.

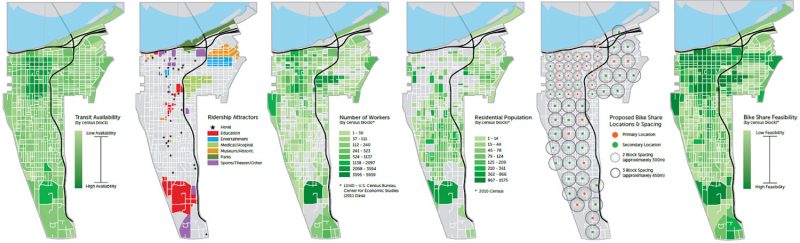

The University of Oklahoma’s Institute for Quality Communities has documented Louisville’s night-and-day transformation in a research project published in December 2014 where aerial images from the 1950s are overlaid with modern views. Luckily, Louisville was included in the southeast region, and the institute has allowed us to share it here with you.

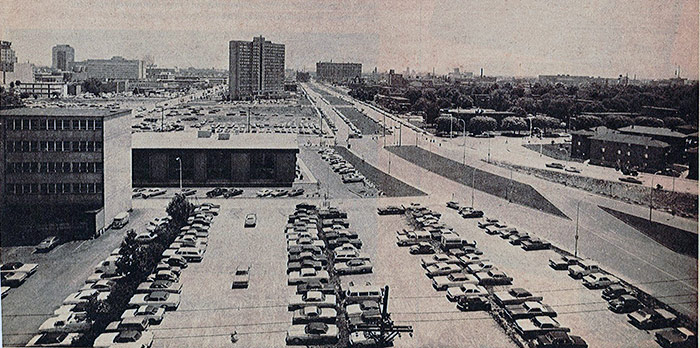

“The most rapid change occurred during the mid-century urban renewal period that cleared large tracts of urban land for new highways, parking, and public facilities or housing projects,” the institute wrote on its website. “Fine-grained networks of streets and buildings on small lots were replaced with superblocks and megastructures. While the period did make way for impressive new projects in many cities, many of the scars are still unhealed.”

(Above: An aerial view of Louisville in 1952 and another view in 2014 shows just how much Downtown and its surrounding neighborhoods have changed. Courtesy TKTK)

Sliding back and forth between the two views reveals 62 years of urban evolution in Downtown and its surrounding neighborhoods. A lot has changed in that time. We’ve built several major Interstate highways through the middle of the city and connected them with an enormous junction, we’ve undergone multiple less-than-sensitive urban renewal campaigns, and politicians through the years have pushed through mega-projects that reshape large swaths of the city in one fell swoop.

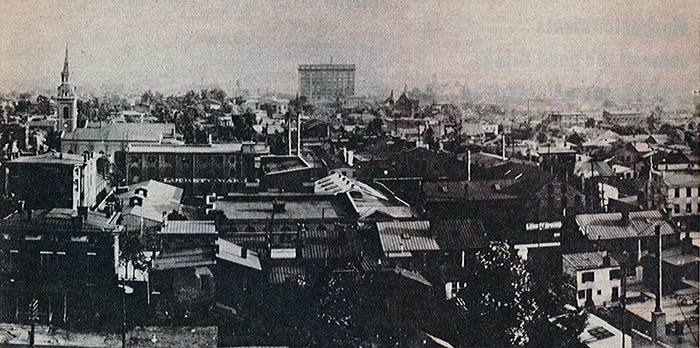

The density in the 1952 view is somewhat astounding. Louisville was once a lively city of fine architecture and bustling streets. But as the city eroded building by building, or block by block, that vibrancy left with it. Today, it’s hard to call Louisville a historic city when you look at just how much has been lost.

Sure, we’ve got some great preservation districts and historic neighborhoods, most notably Old Louisville, but we’ve carelessly tossed aside Louisville’s heritage of urban architecture and there’s no getting it back. To see just how much was lost, we colored in areas in the 1952 image that were torn down since World War II. Take a look below.

(Above: The 1952 map showing in red just how much of pre–World War II Louisville has been lost. On the right, only the areas of pre–WWII Louisville demolished. Montage by Broken Sidewalk.)

A brief note on methodology: We’ve colored in every pre-war block that’s no longer with us. Sometimes these blocks were rebuilt and today contain buildings. Also as likely, they’re now surface level parking lots. We’ve also chosen to include the early housing projects of Beecher Terrace and Clarksdale in this representation. While they were built before the war, they represent an early case of urban renewal, clear-cutting vast swaths of the city’s original fabric. We also included the train sheds and tracks at Union Station on Broadway but not an industrial rail yards on the waterfront. The passenger rail infrastructure could be considered just as significant a loss as much of the city’s built fabric.

While making this updated map, we noticed a few interesting points. First is that much of what was lost was dense yet leafy neighborhoods immediately surrounding Downtown. These areas, around today’s Medical Center, Phoenix Hill, and Nulu on the east and in Russell and Portland on the west. These areas were considered slums at the time, whether they deserved the title or not. Some of them were dirty and overcrowded, but more often they contained people the city wanted to push away, such as a thriving black community in western Downtown.

Also of note is how many parking lots are already appearing on the scene by 1952. You can begin to see the erosion of the city, especially around Broadway with a notably large parking lot at Ninth and Broadway. In an effort to attract suburban shoppers, business owners often would demolish an adjacent structure and advertise free parking. The process was just beginning to speed up around this point.

Another observation is just how many entire blocks were entirely clearcut over the years. Most often, this didn’t happen all at once, with a few notable exceptions like construction of megaprojects like the convention center or the Hyatt hotel. Usually, buildings were lost one by one, like grains of sand falling through an hourglass. It’s harder to notice an entire city slipping away when it happens so slowly.

Finally, it’s also interesting to note the industrial area along the waterfront near today’s Slugger field and north of Butchertown. These areas have been remade today as Waterfront Park and Spaghetti junction, but 60 years ago, they were the city’s hectic industrial quarter.

What’s not as visible on these maps is another kind of change over the past century: transportation. Looking at the modern and historic views, you can discern some streets that urban renewal and highway builders rerouted to speed up automobile traffic through Downtown, but it’s harder to tell the fine grained city that was lost to these realignments. Further, the loss of Louisville’s streetcar network, once among the nation’s best, cannot be left out of a discussion of how the city has changed since the 20th century.

What observations do you see in these maps? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Head over to the University of Oklahoma’s Institute for Quality Communities to view more before and after views from other cities in the Southeast including Nashville, Memphis, New Orleans, Atlanta, Charlotte, and more.