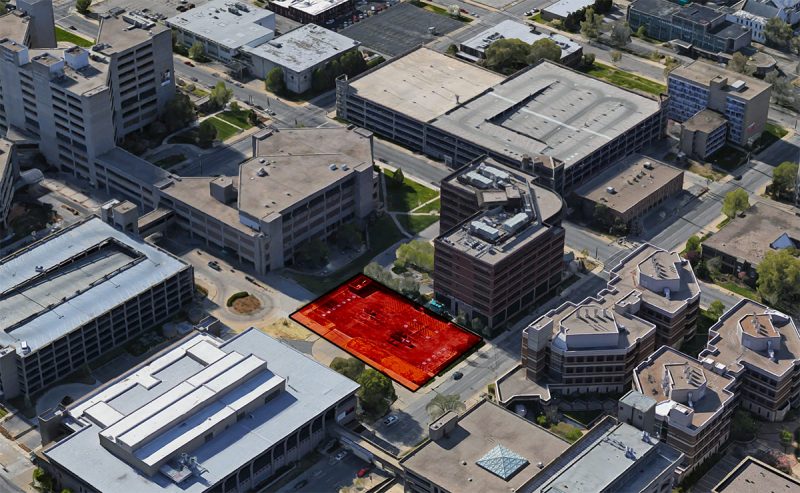

A sturdy, orange-brick building has been keeping SoBro clean for almost a century. Puritan Uniform Rental’s simple yellow lettering above its doorway at 206–208 West Breckinridge Street near Second Street has long been a fixture of SoBro, playing off the building’s signature brick color.

But since the business closed several years ago and the passing of Puritan owner Ernest Carl Bowen, Jr., in 2014, that orange edifice began to collect dirt and grime. Last fall, the structure was acquired by Spalding University with plans for its demolition.

For Spalding, the building has become an eyesore that makes attracting students more difficult, but for a neighborhood already beset with surface parking lots, the building means a lot more.

“The dry cleaners actually did a lot of work for the Sisters of Charity,” Spalding President Tori Murden McClure told Broken Sidewalk on a tour of the property last week. “They did all the habits for the sisters who were working in the area, and they did all the linens for the residence hall.”

The structure has roots within the community.

Plans for the Puritan Building date back to October 1914 when the Benzole Garment Cleaning Company, headquartered at Third and Chestnut streets Downtown, announced they would build a new plant at the site, previously a residence.

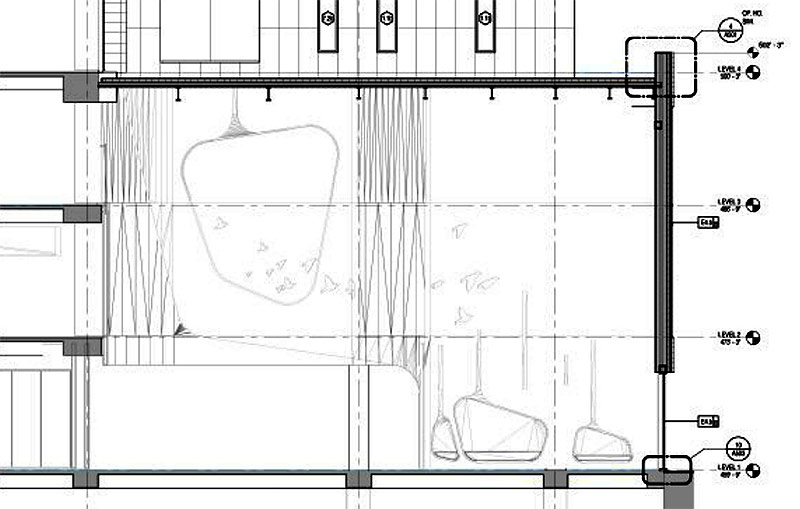

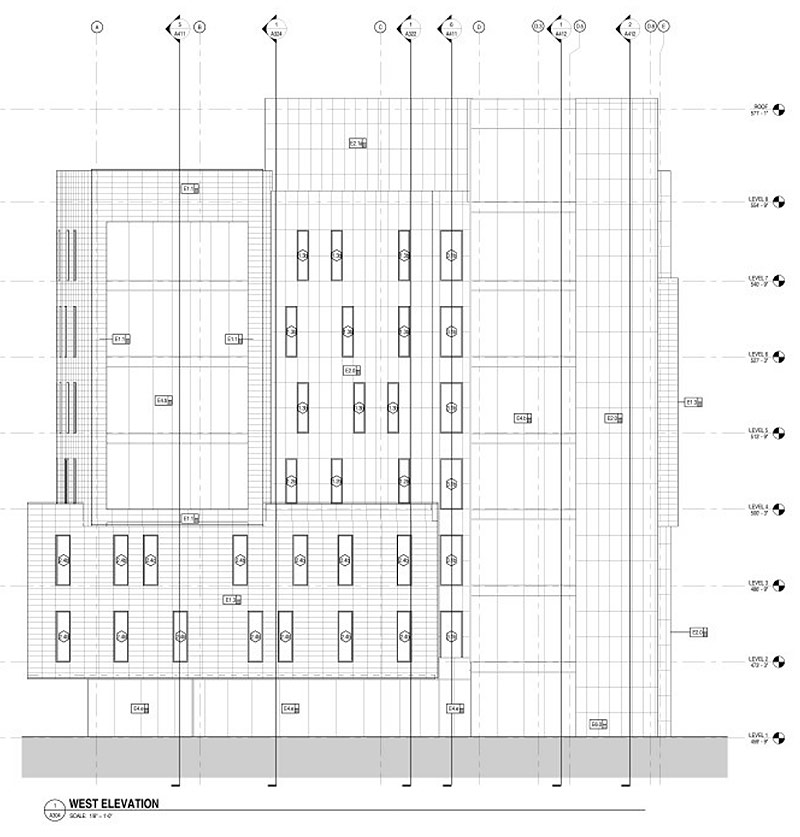

That structure was completed in 1917 under direction of architect Oscar Reuter1. According to a report in the journal Domestic Engineering from that year, the 30-foot-by-200-foot plant was built of fire-proof brick and concrete at a cost of $5,500, or about $103,300 today. And walking around the interior today, it’s clear that this building was built to last.

The site has operated as a cleaner almost consistently throughout its life. After the floodwaters of 1937 inundated the area, the Benzole company went bankrupt, and by 1939, Puritan Cleaners was listed at the site, formally incorporated in 1941 at 206 West Breckinridge Street.

A rapidly changing neighborhood.

Shortly after the turn of the century when the Puritan Uniform Rental building was built, SoBro was undergoing distinct transition. The neighborhood was first developed following the Civil War as a residential enclave of Louisville’s top families, but according to the 2007 SoBro neighborhood plan, it was quickly changing with a greater mix of residents and commercial uses spilling over from Downtown.

This push south also brought with it the neighborhood’s eventual decline. New businesses, including many of the city’s first car dealerships, converted or demolished housing for commercial use, the neighborhood plan continued. During this transition, the wealthy continued south to Old Louisville and old mansions were quickly converted into apartments and rooming houses. “Seemingly overnight, the neighborhood south of Broadway would go from being a handsome Victorian-era neighborhood to an amorphous commercial and tenement district,” the neighborhood plan reads.

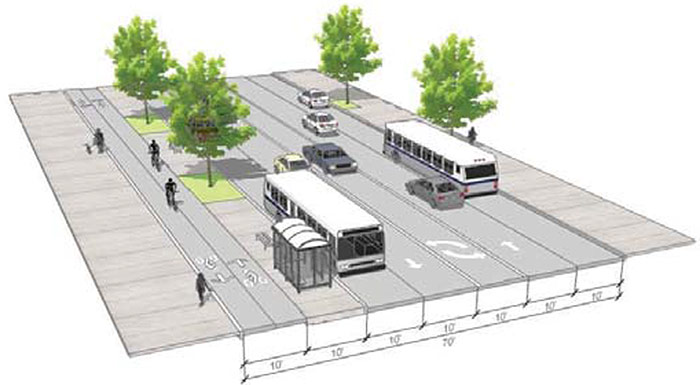

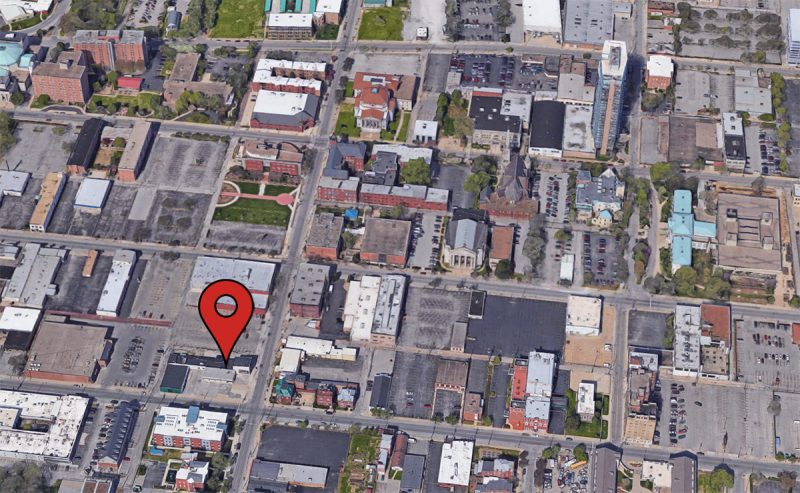

Over the course of the next half century, SoBro would take on a reputation more for its barren parking lots than its historic architecture. Earlier this year, the neighborhood was named the country’s worst “Parking Crater” in a national competition held by New York–based Streetsblog.

“There’s the joke that we’re the giant parking lot between Downtown and Old Louisville,” McClure said. And Spalding has been trying to counter the plague of asphalt with fields and trees, most notably with the creation of Mother Catherine Spalding Square near the heart of its campus. The university also plans to convert a former used car lot at Second and Kentucky streets into a grassy play field for its students.

“The lack of architectural cohesion and the absence of continuity in urban form create a vortex effect for the SoBro neighborhood,” its neighborhood plan continues. “As a result, it has become a ‘placeless’ no-man’s-land that interrupts the connection between Downtown and Old Louisville/Limerick.”

SoBro shows signs of life.

Today, most of SoBro’s grand mansions are gone, but the neighborhood still clings to its mixed-use heritage of proud housing and commercial space. Since 2007, several missing teeth around Second and Breckinridge streets have been infilled in with housing for the Louisville Family Scholar House, the Center for Women & Families, and with a dormitory for Spalding. Some older commercial buildings have been renovated for private and academic use. A Kroger grocery still keeps the neighborhood supplied with food. In many ways, the resurgence of SoBro is centered right around the Puritan Uniform Rental building.

But if Spalding’s plans advance, the Puritan building won’t play a role in that revitalization. President McClure said the university planned from the outset to demolish the structure because they consider the property an eyesore.

The problem for Spalding, McClure explained, came when admissions tours would walk prospective families past new parks and renovated classrooms on the main campus east to the new dormitory nearby the Puritan. She said the sight of a vacant property was turning prospects away.

“Our admissions folks literally talk about how they have to be creative to get past this building without the parents just deciding, ‘No, our child is not coming here’,” McClure said. “It’s not an advertisement for our neighborhood.”

But, then again, neither is another parking lot. And as we toured the former Puritan Uniform Rental structure, a larger, and more difficult, challenge lay just across the street: a homeless man sleeping on the sidewalk.

Questions over contamination.

Before Spalding closed on the property last November, the university hired Louisville-based environmental firm Micro-Analytics to test the site for possible contamination from its former use as a dry cleaners and to prepare a Property Management Plan to submit to the state for the site’s use as a parking lot, calling for capping the site with asphalt.

Our review of Micro-Analytics’s findings in its “Limited Environmental Site Assessment” did show groundwater contamination in excess of the EPA’s Regional Screening Levels. Four chemicals typically associated with gasoline, not with dry cleaning, were detected in groundwater deep under the structure. A source familiar with such contamination said these groundwater issues are not uncommon to urban parts of Louisville where industry has been polluting the community for centuries.

“These aren’t really even chemicals a dry cleaner would have used,” the source said. “This particular site might not be where these chemicals originated from.” The environmental report turned up no soil contamination. “For this property, the depth of ground water is so great, there’s really a small chance of any problems,” the source added. “It’s generally just a precaution.”

Still, the Puritan Uniform Rental building sits awaiting its day with Spalding’s wrecking ball, its yellow letters replaced with yellow Intent to Demolish signs.

A neighborhood opposed to demolition.

But not everyone in SoBro finds the Puritan Building to be an eyesore. “The act of demolishing a handsome anchor building such as the Puritan is anything but sustainable or compassionate,” Stephen Peterson, a Limerick resident adjacent to the Spalding campus, told Broken Sidewalk. “Without these older commercial buildings we can’t welcome new investment into the area—at least not as easily.”

Peterson pointed to the successful renovations of the stylistically similar Milk Building into offices for Genscape and the conversion of a former LG&E structure, itself on a contaminated site, into offices for Metro Louisville and the Kentucky Agricultural Extension as examples of the type of development SoBro needs. “The neighborhood deserves better than another swath of asphalt,” he said.

Thomas Woodcock, an attorney and president of the board of Preservation Louisville, agreed with Peterson. “We don’t want to see the building demolished,” he told Broken Sidewalk. “We really hope there’s some way for Spalding to use the building in some capacity without removing it.”

The SoBro Planned Development District plan from 2011 backs Woodcock’s call for preservation, noting that “existing structures that are identified locally or nationally as having significant historic character should be retained” rather than demolished. The plan adds that sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places—and the Puritan building is eligible—should not be torn “for the creation of surface parking lots or open space.”

“The principles for development in the Neighborhood Core Subarea are to encourage an eclectic mix of modern development within the historic fabric,” the plan reads. “This could result in lively street activity, provide multi-family housing opportunities, allow for businesses that will support both the neighborhood and Spalding’s students.”

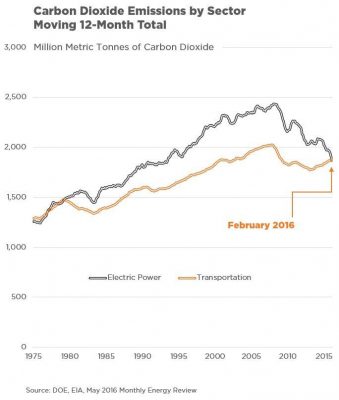

Woodcock and Peterson have watched too many buildings in SoBro succumb to parking lots over the years, adding nothing to the neighborhood’s vitality and contributing to Louisville’s Urban Heat Island problems.

“I grew up in Old Louisville,” Woodcock said. “People were talking 20 years ago about the SoBro area and how many buildings had been demolished. We want to see the building saved using adaptive reuse.” He added: “We’re willing to help.”

Can a compromise be reached?

Perhaps Spalding can reach a middle ground that would clean up the Puritan Building’s act, benefiting both the university, its students, and the neighborhood. After all, everyone agrees more parking lots are not the answer.

Could the Puritan Building, a complex of three commercial storefronts, be revitalized instead to create a real neighborhood asset? Sometimes it takes the threat of demolition to spur a community into action—and we certainly hope that might be the case here.

So far, President McClure has been open to discussion. While she said Spalding is not interested in developing the structure itself, it could potentially partner with a local entrepreneur to give the building new life. “We hoped for a long time someone would come along and buy it,” she said.

It’s now or never for the Puritan Building. “I’d sell the building for what we paid for it,” McClure said. “If someone assured me it wasn’t going to look like this, and wasn’t going to stay like this.” Spalding paid $255,000 for the complex last November, according to a deed on file with the Jefferson County Clerk’s Office.

But for McClure, the clock is ticking. “They have a couple weeks, sure,” she said. “I all but promised the students the building would be gone when they came back.” We’re hopeful this spirit of community improvement can help make an asset of the Puritan Uniform Rental building for Spalding and for SoBro.

Let’s make this work.

If you’re interested in working with Spalding to renovate or purchase the Puritan Building to improve the SoBro neighborhood, please get in touch with Broken Sidewalk right away and we can help make the appropriate connection that could save the Puritan Building. Just email us at tips@brokensidewalk.com. We’re always listening.