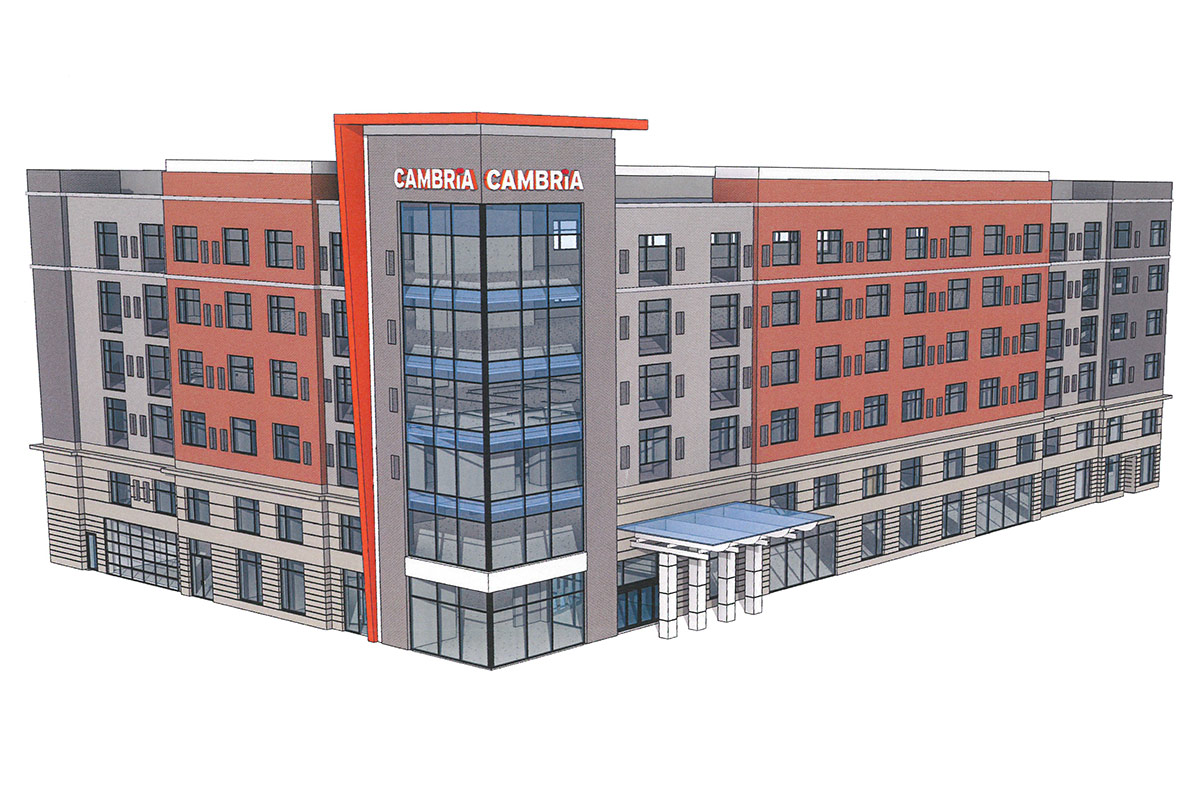

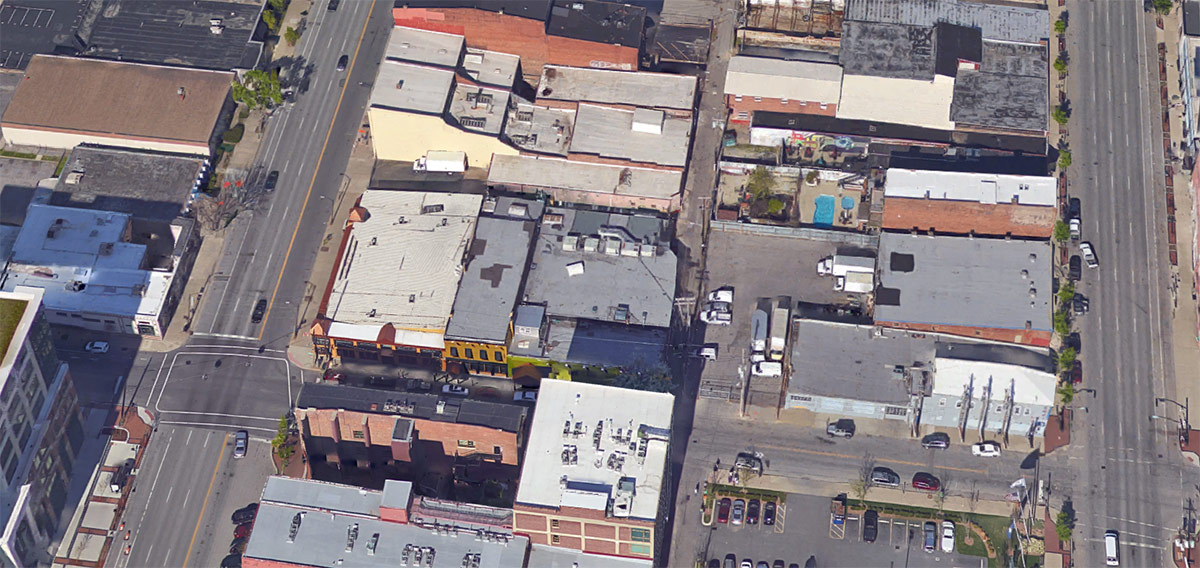

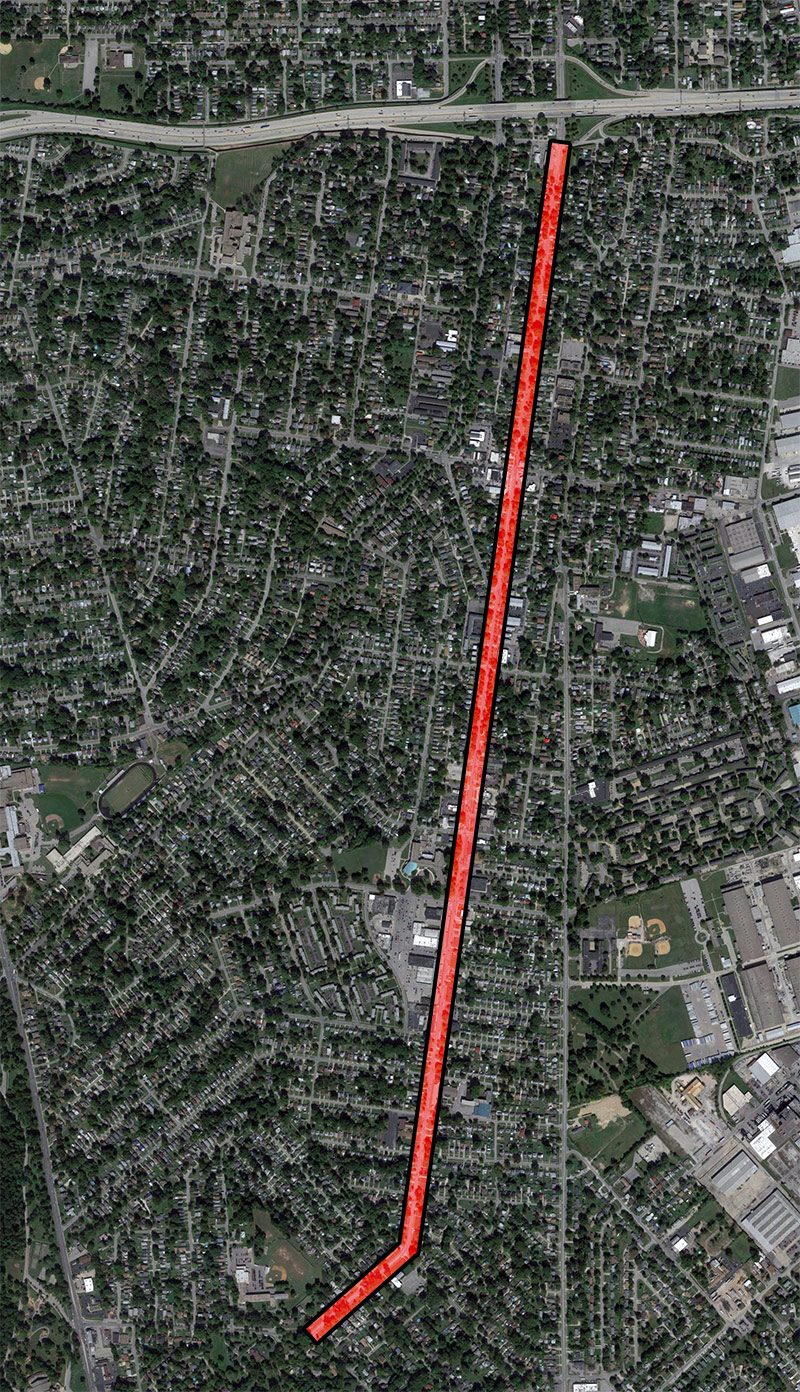

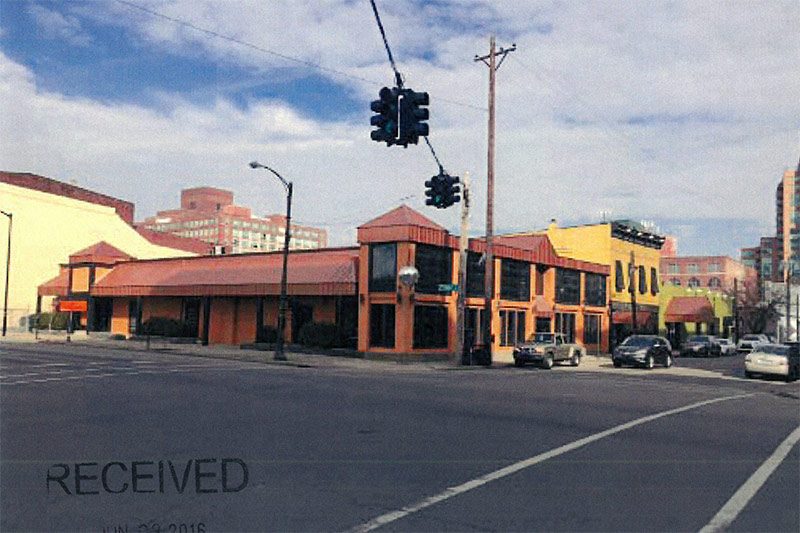

Plans have been filed with Metro Louisville for a six-story, 128-room Cambria Hotel proposed for the former Connection nightclub on the corner of Market Street and Floyd Street in Downtown. The $22 million project would rise 85 feet from the sidewalk on the eastern edge of Downtown near Slugger Field and the University of Louisville’s Nucleus campus.

Broken Sidewalk wrote about the planned hotel back in March, but then the deal was shrouded in a confidentiality agreement. Connection owners George Stinson and Ed Lewis of SLS Management have the properties at 120 South Floyd Street and 243–253 East Market Street under contract with Maryland-based Choice Hotels, which operates the Cambria brand.

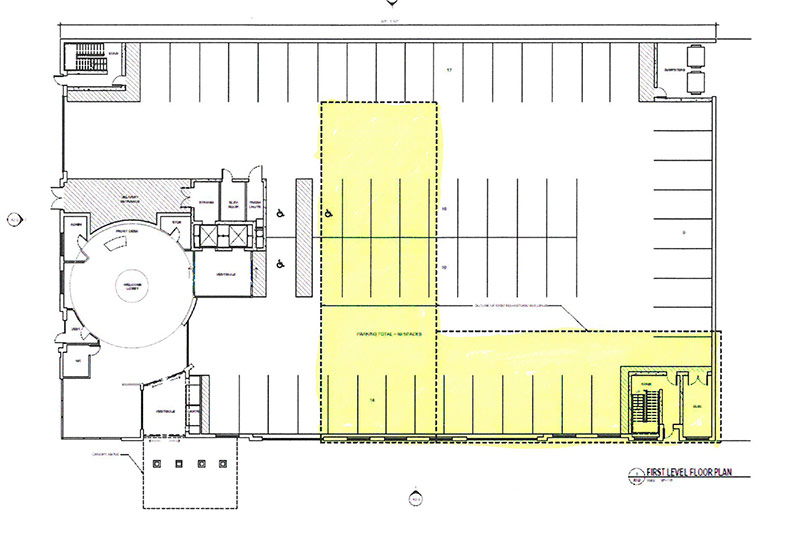

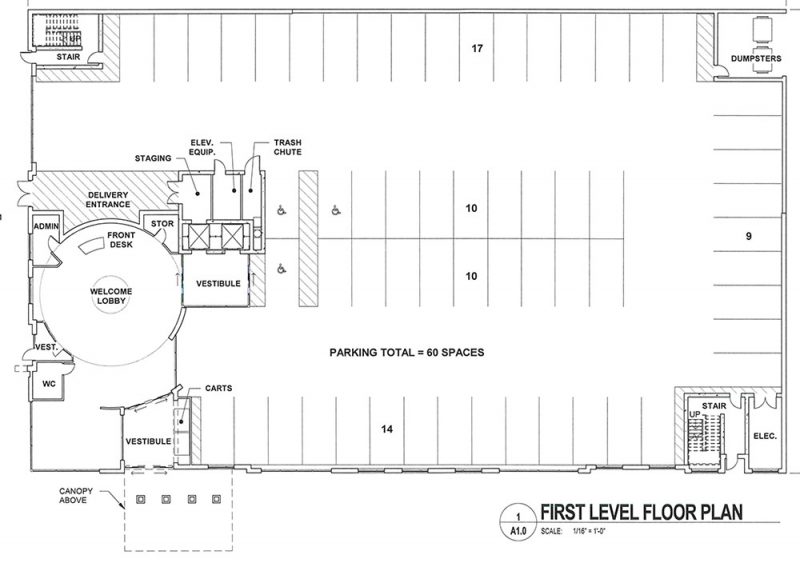

The hotel proposal has been designed by Louisville-based TBD+ Architects. Plans show the building would cover 111,400 square feet over its six floors and calls for 60 car parking spaces and two bike spaces on the ground floor. A 23-foot-wide entrance to the parking lot is shown facing Market Street. The corner entrance would lift guests up to the second floor where the hotel reception and amenities begin. No retail is planned.

The structure itself is clad with limestone on its first two stories with brick above, according to sample sheets provided in the hotels application letter. Developers provided few details of the project’s materiality in their application. The design is fairly fairly generic, but it generally adheres to the guidelines outlined in the East Main–Market District of the Downtown Form District in which it sits.

“The building design is in keeping with the massing and materials of the historic district,” the architects wrote in the development application.

That form district, according to Louisville’s Land Development Code, is intended to “create a downtown with a compact, walkable core and a lively and active pedestrian environment that fosters and increases the number of people walking and to ensure a more humane environment.”

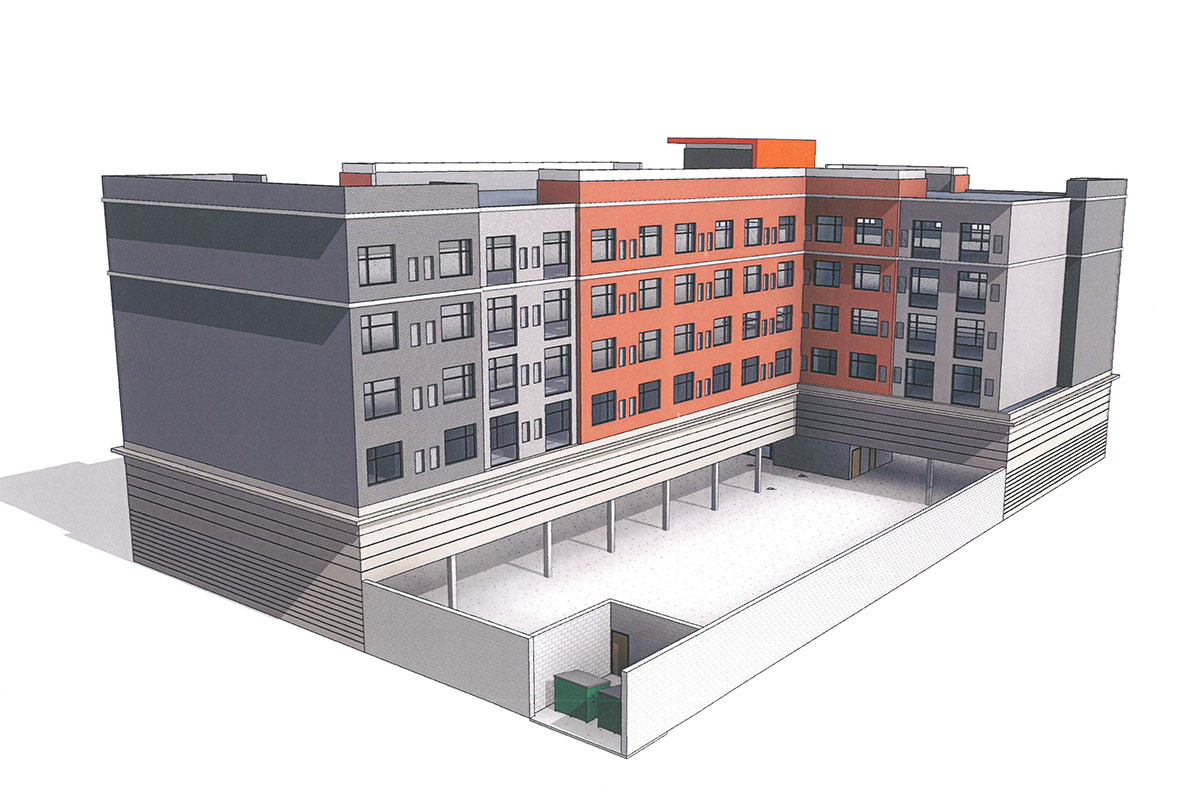

While the structure meets the guidelines, it does little to enhance the sidewalk experience along Floyd and Main streets. The surface level parking ensures there will be little activity on the sidewalk level, a wide curb cut on Market means pedestrians will have to dodge motorists, and the proposed demolition of two contributing structures will mean Louisville’s historic character is eroded even further.

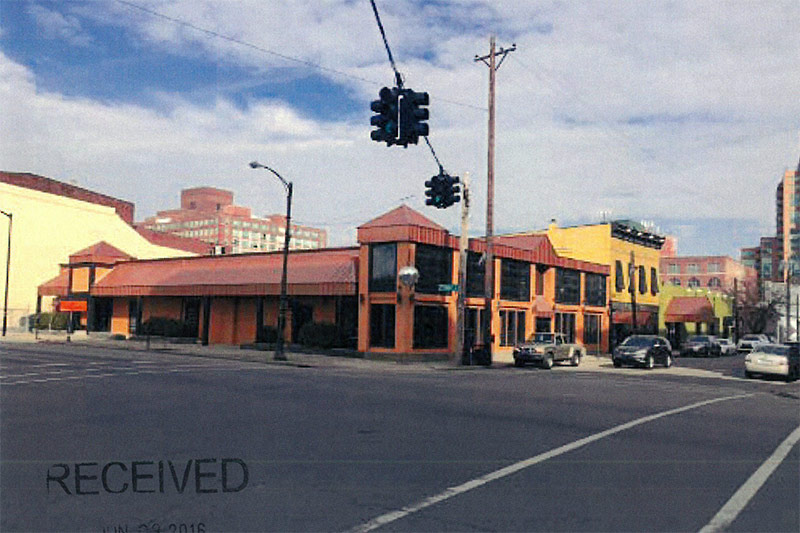

Broken Sidewalk sounded the alarm last year that these two buildings were in danger. “In this case we’re…dealing again with demolition, with outside developers, and with government transparency (or the lack thereof),” contributor Bryan Grumley wrote of the properties.

Grumley’s report went on to note that the Connection site has some protections. “This plot is subject to Downtown Development Review Overlay (DDRO) oversight,” he wrote. “For perspective, so was the Omni development where we’ve recently weathered the demolition of multiple NRHP-listed structures.”

The architects at TBD+ submitted a Historic Building Analysis on behalf of the developers, which, unsurprisingly, finds no reason to preserve the existing structures. “With this analysis, we are requesting that the two contributing structures located with (sic) the proposed development be approved for demolition so that the project can move forward.”

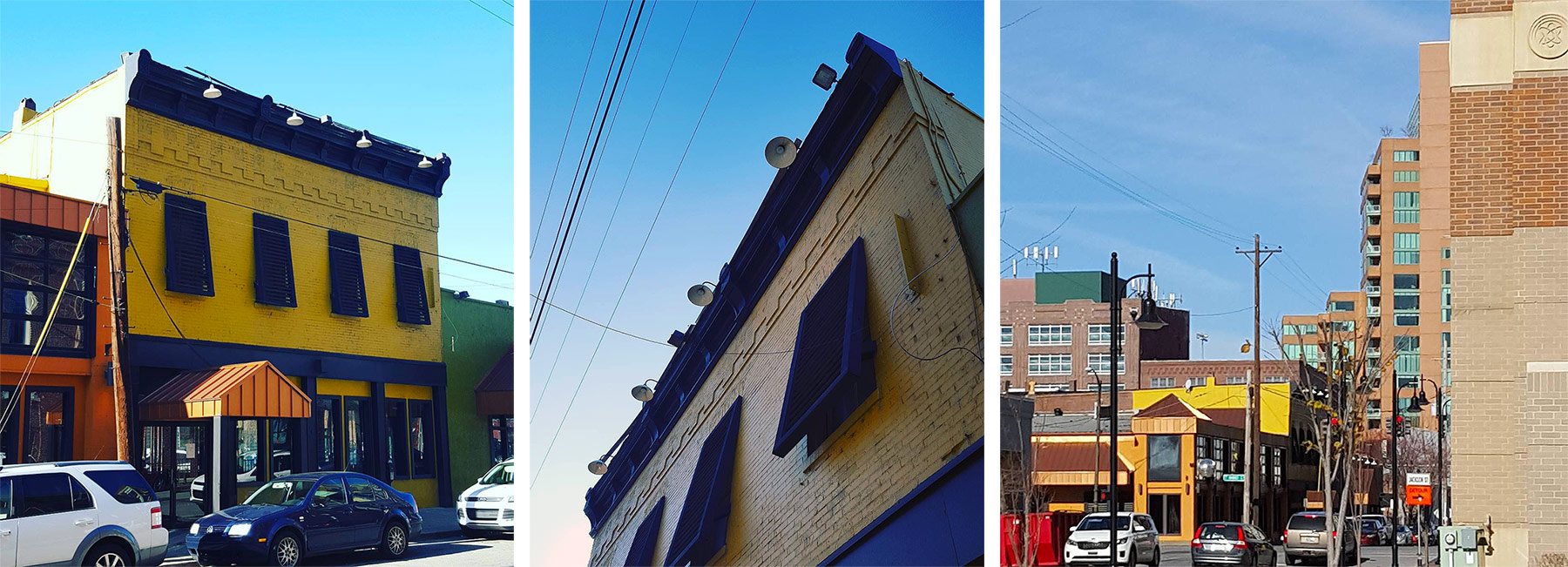

The report claims that the existing structures have been “significantly modified” and lack architectural merit. While the two buildings in question can’t compete with the Seelbach Hotel for architectural merit (and neither can the Cambria proposal, for that matter), they represent a quickly disappearing segment of Louisville history: its industrial heritage. These vernacular buildings were built plainly, but sturdily, and offer easy opportunities for adaptive reuse when a creative proposal comes along.

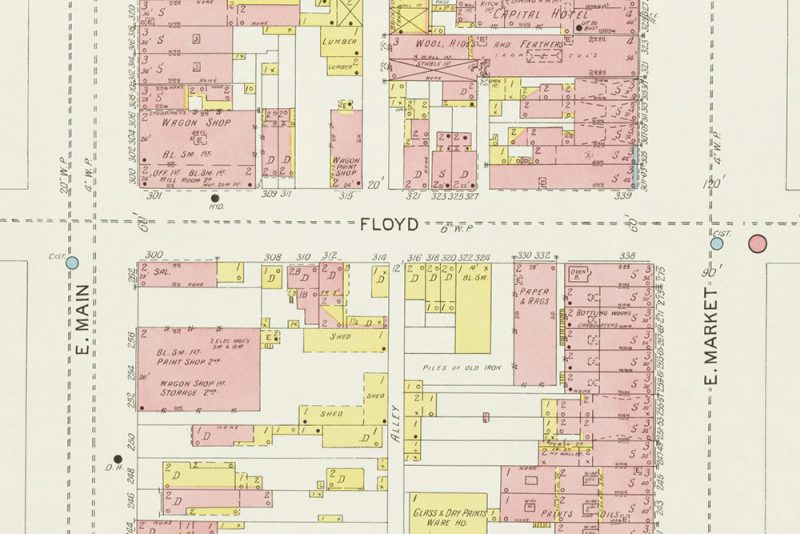

These types of buildings were crucial in the development of Louisville, but they often lack the same history of structures built in more polished quarters of the city. This was the ragtag Haymarket district, where crowded streets were full of farmers carts hocking their crop. It was fairly gritty, with industrial rail yards to the north where Slugger Field stands.

The two-story brick structure in this case dated to sometime between 1892 and 1905, according to Sanborn maps of the area. It began humbly as a junk shop collecting paper and rags in an intensely mixed-use area that included shops, houses, blacksmiths, wagon makers, saloons, and “piles of old iron.” An account of a similar facility in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, recalls that children would collect scraps of paper, rags, and other rubbish to sell to such junk shops. It was a sort of early recycling.

Despite the architects’ report, the structure’s facade appears to be mostly intact. It’s unclear what lies below a new storefront, but it’s likely limestone columns given the proportion and scale of the windows. Such a system would have been common for buildings of this vintage. The report claims that decorative stone lintels have been removed, but our reading of the structure shows the arched, rusticated brick above the windows matches similar rusticated brick details along the cornice line, meaning this building likely never had stone lintels. And given its history as a junk shop, that would certainly be fitting.

The one-story building to the north was built later in 1925 for industrial purposes, and we weren’t able to track down its use. (Let us know if you know more.)

As is usual in Louisville, the choice to demolish these structures comes down to parking. “If the existing building (sic) were retained it would limit or significantly reduce the number of parking spaces proposed for the site which would keep the project from moving forward.” The report also cites increased costs associated with keeping the buildings that developers aren’t willing to pay.

The architects also ruled out a facadectomy, or incorporating the facades of the structures into the new building. Such an option is not preservation, but has been a compromise solution for projects like the Downtown Marriott and Aloft hotels. The report states that the hotel’s floor-to-floor height (12 feet on the first two floors, then 10.5 feet for the rest) would not line up with the existing buildings.

The report ends bluntly: “The project will not move forward if the existing structures have to be incorporated.”

But does a former junk shop deserve to end up at the landfill? How do we balance preserving our rapidly dwindling supply of vernacular industrial buildings with new development? Those questions will have to be answered by the Downtown Development Review Overlay committee at a future hearing. But with an ultimatum already declared and the DDRO’s past history, it seems like there’s little hope for old Floyd Street.

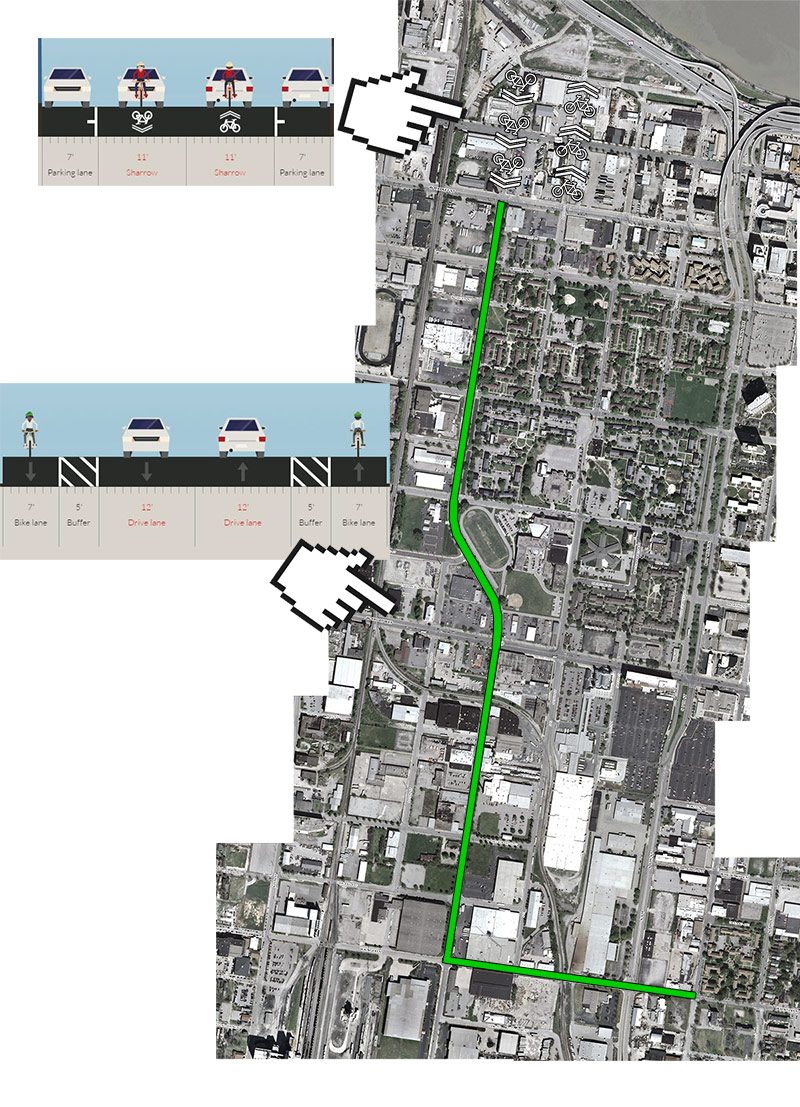

But the biggest design flaw of the Cambria project is the orientation of the parking itself, along the sidewalk level. Were the project to move forward, the ground floor of this structure would present a dead face to the street.

But there appears to be an easy design fix that would allow almost all of the ground floor to include retail space. Sinking the parking one level into the ground, ramping down from the garage entrance and wrapping around using a path similar to the existing plan. If the parking entrance were located off the alley, even more space could be potentially freed up. Such a move would add some cost to the project, but it could also add additional parking spots and would provide income-generating retail space.

[Top image is a montage of a rendering provided in the application overlaid onto a street view image. It may not reflect the reality of how the final building may look and is meant for illustrative purposes only. Montage by Broken Sidewalk.]