Have you been to the Parklands of Floyds Fork yet? Visiting the pristine landscapes on the far eastern edge of Jefferson County is like “being dropped off in Yellowstone,” Scott Martin, parks director at 21st Century Parks, told Broken Sidewalk’s Matthew Beck. Beck was writing this past May about how unchecked sprawling development around the 4,000-acre series of parks in consuming some of Louisville’s last farmland and forests.

This month, WDRB’s Sterling Riggs published a special report on another threat to the Parklands: contamination along Floyds Fork that could potentially make people sick. Riggs worked for several months with an environmental group Salt River Watershed Watch to test the creek waters.

According to Riggs:

It looks inviting, but some are alarmed by what’s in the water. WDRB collected water samples in May, June and July at the Parklands’ multiple parks to reveal the amount of fecal coliform in the popular creek. Fecal coliform is bacteria found in human and animal feces and can lead to ear and skin infections and gastrointestinal illnesses.

The state requires water to be tested five times a month. If the geometric average of fecal coliform is above 200, swimming is not recommended and is considered hazardous to your health.

“We’ve had some above and some below. You cannot conclude that the entire area is grossly contaminated,” Bob Fuchs, a chemist at Astbury Water Technology in Clarksville, Indiana, told Riggs. Still, Fuchs said he would not advise swimming at the Parklands. The report also notes that the levels were safe for kayaking.

It’s important to know there’s a problem, but what’s the cause? It turns out the contaminated waters are largely due to sprawling development in the area. Way down in the story’s 25th paragraph, Riggs writes, “Research shows bacteria levels have increased over the years, because more homes are being built along the creek.”

“The land is what you need to look at,” Russell Barnett, a volunteer at the Salt River Watershed Watch and director of the Kentucky Institute for the Environment & Sustainable Development at the University of Louisville. “If you look at the land, that’s a mirror of what the water quality is going to be.”

A 2014 study of the Chesapeake Bay watershed called “Polluted Runoff” revealed that developed land can make waterway pollution worse. And the contaminants don’t just include fecal coliform, they also include more toxic fertilizers and chemicals that keep sprawling lawns green to road salt and heavy metals that fall off passing cars. According to the study:

Rain water increases in speed as it flows across developed landscapes. And as the water accelerates, it warms, picks up anything left in its way, erodes stream banks, and pollutes the water into which it flows.

The list of pollutants in runoff is long. Trash dropped on the street. Nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizers on lawns and air pollution that settles on the ground. Fecal bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens from animal and human waste. Oil and toxic petroleum products from vehicles and driveway sealants. Pesticides and herbicides from lawns and gardens. Road salt. Dirt from stream banks and construction sites that lack runoff control fencing. Toxic metals, such as copper, lead, and zinc from vehicles, roofing materials, and paints.

The brake linings of cars and trucks are often made with copper, and they shed a fine dust of this toxic metal onto streets. The Maryland Department of the Environment sampled runoff from the state’s major urban areas and found copper in 92 percent of the samples. Fifty-three percent of the time the levels would be acutely toxic to aquatic life. (Copper also appears in waterways because, among other reasons, the metal is an ingredient in herbicides.) Zinc from car tires, road salt, paint, and other products has also been found in runoff, as well as the toxic metals lead, chromium, and cadmium.

“Cars are very significant, because we build so much infrastructure for the cars—the parking lots, roads, garages, and driveways,” Dr. Robert G. Traver, a professor of Civil Engineering at Villanova University, said in the report. “It’s the pollution from the cars, but it’s more than that. It is, for example, the heat of the water that comes off the pavement and the volume of the runoff from the pavement.”

Barnett also listed a number of other contributing factors to increased levels of contamination. “Waste water treatment plants, septic tanks—it could be from any type of animal that you can think of, warm blooded, cold blooded,” he told Riggs.

“Conditions have worsened,” Karen Schaffer, a retired environmental consultant and Salt River Watershed Watch volunteer, told Riggs. “When the stream flow is higher because of recent rainfall, that’s when the bacteria levels tend to be higher.”

And this problem stands to get much worse in coming years. With continued sprawling development around the park and ill-advised roads that Metro Louisville plans to build to open up the area on the far side of the Parklands for development, Floyds Fork will likely become even more contaminated.

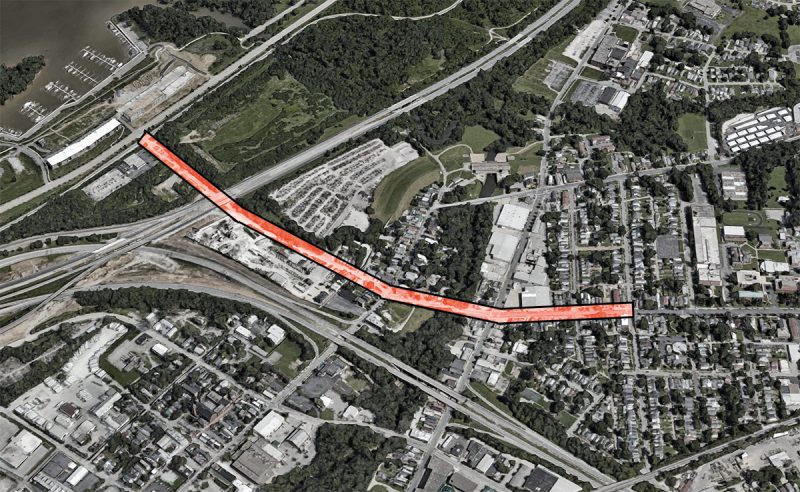

[Top image of Floyds Fork courtesy Metro Louisville / Flickr.]