How has your neighborhood changed over the past 20 years? Has it become more prosperous? Is it undergoing a development boom? Is it still shaking off the effects of the Recession and subsequent foreclosure crisis? A lot can happen in two decades—and sometimes a lot can stay the same.

Attend the planning commission meeting on Monday, March 21 at 6:00p.m. at the Old Jail Building, 514 West Liberty Street.

In Old Louisville, the past 20 years have seen something of a residential renaissance with mansion after Victorian mansion being fixed up around Louisville’s finest historic district. But with all those houses seeing new life, why is commercial development so slow to keep pace along the neighborhood’s main drag, Oak Street?

That question has been causing growing tension among Old Louisville residents trying to figure out how to jumpstart development along Oak. It seems everyone is frustrated with the situation, but not everyone agrees on the path forward. Just what approach should be taken—and what exactly is holding the corridor back—is hotly debated.

And this Monday, March 21, the Louisville Metro Planning Commission will serve as arbiter to a rezoning concept that would change how and where development and preservation take place in the neighborhood. It’s a complicated story, but the future of Old Louisville’s historic Oak Street is in the balance.

We’ve broken this longform story into parts to help make it more digestible, but we highly recommend familiarizing yourself with the details, which we explore in detail, below.

What’s all the fuss about?

Above: Familiarize yourself with the Oak Street corridor with the images above, all from Google Street View.

Simply put, it’s about zoning. Or rather how and where commercial development should be allowed to take place in Louisville’s most historic neighborhood.

The Planning Commission will decide whether Old Louisville should be rezoned from an innovative but complex zoning code called Traditional Neighborhood Zoning District, or TNZD for short, to the more common C2 zoning use list that covers much of the rest of the city. It will also deliberate whether the area zoned for commercial use should be expanded to include historic single-family homes.

One side of this debate believes that TNZD should be modified to make it more inclusive to business while the other side wants the commercial portion of TNZD largely scrapped and and replaced with C2 to more readily match the rest of the city. The neighborhood worked on and fiercely debated this point for years before coming to a resolution in 2015, voting to proceed with the latter group’s C2 proposal.

But then a new concept of expanding the boundaries of the commercial district was introduced by District 6 Councilman David James—without a neighborhood vote—which stirred up all the old controversies as Louisville’s Planning & Design staff began to study the issue ahead of the Planning Commission meeting.

Table of Contents

How does TNZD work in Old Louisville?

Oak Street used to be zoned C2

Momentum building along Oak Street

Can Oak Street support more development?

Debate at the Old Louisville Neighborhood Council

The motion makes its way to City Hall

What is TNZD?

The story of TNZD goes back about 20 years, according to Roberto Bajandas, an Old Louisville resident, architect, and developer who had a hand in crafting the code in the late ‘90s.

“So in 1998, the Zoning & Land Use Committee (ZALU) of the Old Louisville Neighborhood Council (OLNC), of which I was a member at the time, decided to do a new downzoning,” Bajandas explained. Using the Cherokee Triangle as an example, the ZALU Committee worked with a team that included urban planner Charles Cash under then Mayor David Armstrong’s planning department.

“Essentially, TNZD tries to have historic preservation and zoning / land use be coordinated, so that each lot is zoned by historic characteristics,” Bajandas said. For instance, if a house was historically a single-family home, someone couldn’t come in and turn it into apartments under TNZD. Likewise, commercial properties couldn’t be converted into some uses incongruous with the historic character of Old Louisville. That meant no gas stations, car lots, drive-thrus, and the like.

“The TNZD is designed to recognize historic or long-established traditional neighborhoods and to protect them as a distinct pattern of development,” Louisville’s Land Development Code reads.

This was some seriously advanced stuff for the late ‘90s—and it’s still pretty cutting edge today. The plan was to bring similar TNZDs to all of Louisville’s traditional neighborhoods, with Old Louisville serving as the model.

“Originally, the thought under Cornerstone 2020 was that every form district would have a parallel zoning district,” Charles Cash told Broken Sidewalk. “The thought was this was creating a flexible tool that then could be used to implement a specific plan for a specific neighborhood.”

Cash had a front-row seat for the creation of TNZD, working before and after merger in various planning capacities, such as planning director and the Mayor’s representative on the Planning Commission.

The spread of TNZDs across the city hit a wall because of the energy required for implementation and to coordinate them with specific neighborhood plans. “It was unmanageable,” Cash said. “Shortly after merger, the idea evolved into having planned development districts,” a similar model to TNZD that could be implemented anywhere in any form district, whether they’re old or new.

Ultimately, because the TNZD rollout was limited to Old Louisville, problems have arisen today that contributed to today’s zoning conversation. The big questions at hand: Does TNZD confuse business owners and developers because it’s different than C2? Has that confusion kept development away from Old Louisville?

How does TNZD work in Old Louisville?

The majority of the Old Louisville TNZD map is yellow, indicating single-family houses in what’s referred to as the Neighborhood General. But mixed in are a variety of multi-family, commercial, institutional, and other designations. In this story, we’ll be talking about three commercial notations: Neighborhood Center, Neighborhood Transition-Center, and Corner Commercial.

The TNZD was designed to be flexible for development while protecting the historic, urban nature of a neighborhood. It regulates the uses in buildings based on the site’s history and location to promote land uses that are appropriate in historic neighborhoods. The document doesn’t stipulate architectural style, but instead encourages a variety of styles and forms. It also helps keep a neighborhood compact and walkable by lowering parking requirements over traditional zoning.

Three main commercial zones were designed to create a gradient of development intensity, ramping up toward the heart of Old Louisville’s commercial district at Fourth and Oak.

“The Neighborhood Center is intended to serve as the commercial center and main public meeting space for the surrounding neighborhoods,” the updated Old Louisville/Limerick plan from December 22, 2000, reads. “An important element of the area is that commercial uses are required on the ground floor level.” Typically promoted to be four stories, buildings in this area also include office or residential uses above the ground floor.

“Neighborhood Transition-Center is intended to act as a transition area between the Neighborhood Center and the Neighborhood General,” the document reads. “The permitted uses are to be similar to the Neighborhood General but also allow for a more intensive usage such as professional office, and multifamily and some limited retail uses.”

“The corner commercial building was and remains an important element in the traditional neighborhood, bringing goods and services within walking distance of residents,” the document reads. “Some of the buildings were originally built to incorporate ground floor commercial while others began as detached houses and were later modified and typically extended to the sidewalk in order to accommodate commercial businesses.”

Each of the specified designations was plotted on a parcel-by-parcel basis on the TNZD map after careful study of each property. But that doesn’t mean the map is set in stone. Just like zoning in the rest of the city, property owners can petition for changes to a number of elements governing his or her property.

“Remapping a property is just like getting a zoning change,” Cash said. “As I recall, there have been some that have been reinterpreted that were incorrectly mapped.”

Has the TNZD worked?

That question is at the center of today’s zoning debate. Many are pointing to an underperforming Oak Street and blaming TNZD while others say TNZD works and that Oak Street is stagnant for a variety of other market conditions. But there’s one place where TNZD has been a resounding success: reviving the neighborhood’s housing.

“TNZD has been very good at promoting residential development,” Cash said. “Clearly its support of residential development is a very positive story.”

“The revitalization of the residential Neighborhood General has been dynamic and very much fostered by the TNZD,” Christopher White, another Old Louisville resident and music professor at the University of Louisville, told Broken Sidewalk. “There are so many more single-family properties.”

White said in the 30 years he has lived on Ormsby Avenue between First and Second streets, most of the houses have gone from apartment houses to a majority owner-occupied home.

But housing and the Neighborhood General zone are not in question at the upcoming Planning Commission meeting—commercial areas are. And many in Old Louisville see the TNZD as bad for business.

The argument goes that, because Old Louisville ended up being the only neighborhood with TNZD while the rest of the city is zones C2 for commercial areas, the difference confuses developers and pushes them to pass up the neighborhood for development.

“Any time you get into a situation where you are limiting businesses, and making it difficult,” Howard Rosenberg, an Old Louisville resident and retired Humana human resources employee, told Broken Sidewalk. Rosenberg is also chair of the Old Louisville Neighborhood Council, but stresses his opinions here are his own.

“This is what I’ve been told because I’m not a business owner,” he said. “When you talk to businesses and developers, they understand C2, which is commercial zoning, they understand C1. When you start to say you can have a pet store, but you can’t have a pet grooming salon, you can have this but you can’t have that, it becomes very difficult.”

There are plenty who agree with Rosenberg, including recent New York City transplant Alex Parets, who is renovating the historic Arden Building at Second and Oak. While TNZD hasn’t affected the Arden renovation, Parets still supports the change. “Anything they can do to encourage more businesses to open in Old Louisville will help,” Parets said. “I think overall support with permitted uses is vague. Fifteen years is enough time for change.”

Parets and his business partner Dustin Hensley submitted letters last July to the city’s Planning & Design staff supporting the change of zoning for a residential building the duo owns at 426 West Oak Street, next door to the old Rudyard Kipling. Rosenberg said that property was once a bookstore.

“We need more active business on Oak Street,” Jeff Blanchard, Old Louisville resident and owner of a Corner Commercial Building at Sixth and Oak streets, wrote in a recent Facebook post. “Rezoning simplifies creating new businesses; it’s as simple as that.”

Old Louisville resident Andrew Owen, a member of the Fourth & Oak Street Task force that recently oversaw the new streetscape in the area, is one of the most vocal supporters of the change. In a letter to the city last July, Owen said he and his task force colleagues had spoken to dozens of real estate professionals, business and property owners, and neighbors who expressed “sincere confusion about the TNZD.”

“Nobody seemed to understand what the TNZD is, what the TNZD allowed and didn’t allow, what the TNZD was designed to do, or what the TNZD had or had not accomplished,” Owen wrote. To be clear, this is not a failing of the TNZD itself—the same ignorance of local policy could be exemplified time and time. But Owen believes the TNZD is holding the neighborhood back.

“What most everyone we spoke to agreed on, however, was that this general confusion has created a barrier to entry for business owners, developers, and property owners which, in turn, has hindered commercial growth in the neighborhood,” Owen continued.

There’s clearly frustration in Old Louisville about Oak Street. People living in the dense neighborhood understandably would like to walk to stores in their own neighborhood rather than drive across town. It’s a point everyone, both for or against the changes, makes about Oak Street.

As that frustration built over the years, the complexities of TNZD provided an easy scapegoat. “Sometime in the last five to ten or so years, the Zoning & Land Use (ZALU) committee started to be populated by people who were frustrated by the lack of commercial development in the neighborhood,” Bajandas said. “Somewhere along the way, a small group within ZALU got the idea that the problem was TNZD.”

At the root of it is the list of permitted uses allowed under zoning. In the TNZD, that permitted-use list is groomed and tailored to the historic district while C2 throws open the option of just about any commercial use, whether it’s compatible with Old Louisville or not.

But does C2’s widespread use in Louisville actually make a difference? Perhaps with a local developer, but not at all with someone from out of town.

“There’s a conception that C2 is some universal list of commercial uses,” Cash said. He said Louisville’s C2 list is as arbitrary as any other list of permitted uses, and that those lists vary widely in name and content by city. Lexington’s commercial zoning list is referred to as B2, for business, while Frankfort’s zoning code calls it CG, or General Commercial. Closer to home, Shelbyville calls theirs C3 for general commercial district.

“There is no universal list,” Cash continued. “There’s some idea that this becomes a universal panacea, that’s simply not true.”

“I’ve been an architect and a developer in Louisville since I moved here from Puerto Rico in 1975. You always look at a list—even if it’s a C2 list,” Bajandas said. “Normally what people are proposing isn’t exactly on the list and you’ve got to work it out with staff. With every project, you have to go through this process and figure out where you sit within the land development code.” It doesn’t matter if that’s a TNZD list, a C2 list, or any other list.

“What currently is there [under TNZD] is a smaller list than C2,” Bajandas said. “It excludes a lot of the things that are against the pedestrian style environment: the used car lots, the new car lots, parking lots, rental lots. All those were excluded. Large buildings that tend to be windowless were excluded, warehouses, a lot of that stuff that would not be pedestrian friendly. It’s a C2–C1 list but geared more for what you might consider an urban neighborhood.”

Oak Street used to be zoned C2

While those supporting rezoning Old Louisville cite 15 years of slow development along Oak Street under TNZD, others remember decades more of slow or negative growth before that when the entire area was previously zoned C2. “The Fourth & Oak area has never developed,” Bajandas said. “Those people that blame TNZD forget that most of it was zoned C2 for decades before TNZD.”

“For many years that’s the way it was,” Cash said. “You had C1, C2 zoning throughout that area. Zoning is not, under any circumstances, a guarantee of commercial development.”

It was in that era when many of today’s problem properties were built, including the vacant Winn-Dixie set behind a massive parking lot, the concrete block strip mall containing a Rite Aid, and a former suburban-style KFC that closed before TNZD was implemented.

“If you look at the map of the Fourth and Oak area, a great portion of what was to become Neighborhood Center was zoned C2,” Bajandas recalled. “The Winn-Dixie was zoned C3. During that period when you had that C2 zoning was when we lost the Blue Boar, the Red Barn, the KFC, the Steak and Egg, Winn Dixie. A lot of those storefronts emptied leading up to the beginning of TNZD in 2002, and it did not improve.”

Cash added that between TNZD and C2 zoning, the latter is much more antiquated, dating back to the 1940s when we were still fleeing the city as a society.

“I believe the time has come to review this zone because questions have arisen over applying 20th Century restrictions on to 21st Century businesses,” Councilman James said in a press release last April. But TNZD was implemented in the 21st century while C2 dates back 70 years. “We have found economic development sometimes being hampered by rules that did not anticipate the kinds of businesses and culture we have in play today,” James continued.

“When Cornerstone 2020 was being completed, there was a discussion about should we go back and update the C2 use list, because they’re kind of antique,” Cash said. “Shouldn’t we update these and make them more related to modern needs? The answer was no. The reason was it might complicate the adoption of Cornerstone.”

And Cash said C2 is failing to produce quality development in other parts of Louisville. “Vast areas of Preston and Dixie highways are zoned C2,” Cash said. “Residents complain pretty much constantly about quality of development they get there. If C2 were a universal panacea you woudn’t be hearing those complaints.”

“It’s been 15 years. If you wanted to update the TNZD use list, I think that’s a reasonable thing to do,” Cash said. “Blanket C2? That doesn’t make a lot of sense. You can’t make automobile uses and drive thrus and filling stations in a traditional neighborhood and do it well. I have tried. It’s like taking an elephant through the eye of a needle.”

Momentum already building along Oak Street

While the debate about whether TNZD is holding Oak Street back or not continues, Old Louisville is already due for a sea change along the corridor, with or without changes to the TNZD. A flurry of development in the past couple of years has a dozen new businesses lining the street and hundreds of office workers filling the sidewalks.

Just southwest of Oak Street, City Properties Group is renovating an old factory into the Edison Center, an office building that will soon be home nearly 300 city employees. Just off Oak on Garvin Street, Genscape recently opened its new corporate headquarters, expecting to eventually bring another 300 well-paying jobs.

While there have been some losses of some long-standing businesses like the Rudyard Kipling (due to personal issues, not zoning), there’s plenty of new retail that has stepped in. At Fourth Street, attorney Joe Impellizeri recently renovated the old Women’s Club building, and there’s now Smokey’s Bean coffee shop inside. Before that, he added new facades to two single-story commercial buildings on Oak and they’re filled with retail such as the well-designed Bottled liquor store.

At Garvin and Oak, a bakery recently opened. A block west, Blanchard just announced that he leased a storefront in his building at Sixth and Oak to entrepreneur Cathe Crabb where she will open Unorthodox, an “art and oddities” shop.

A couple blocks east, Parets continues the renovation of the Arden Building at Second and Oak. Parets told Broken Sidewalk that his newest tenant is graphic design firm from Cincinnati called Studio Post Office, taking the space formerly occupied by a salon at 123 West Oak Street. Other retail stores in Parets’s building include a clothing store, a spin studio, and a soul food café.

In fact, Oak Street today is in many ways as strong as it’s been in a long time.

Can Oak Street support more development?

While there’s a tremendous amount of activity already taking place along Oak Street, how much more can the area support? There’s still room for growth, but making the jump to the next level, including building much needed new mixed-use buildings, will be a challenge for many reasons outside of the zoning debate.

Adding his voice to the pro-zoning change and remapping camp, urban planner Barry Alberts made a presentation to the OLNC in October 2014, outlining his ideas to remake the Oak Street corridor. Alberts is the former director of the Downtown Development Corporation (now the Louisville Downtown Partnership) and principal of Louisville-based CityVisions Associates, a consulting division of Bill Weyland’s City Properties Group. Alberts’s study was funded by Councilman James’s Oak Street Task Force and he is expected to make a similar presentation before the Planning Commission on March 21.

In his 2014 presentation, Alberts recommended rezoning Oak Street’s commercial areas to C2 and expanding the bounds of the commercial district to Seventh Street on the west and Floyd Street on the east, including residential properties within those extents—a remarkably similar plan to what will be discussed at the Planning Commission.

Alberts’s “Oak Street Corridor Development Strategy” plan called for, among other things, focusing on multiple anchor projects rather than hoping for a silver bullet development; higher density housing in mixed-use buildings; infilling vacant corner lots; and adopting an “Arts & Heritage” theme to brand the neighborhood.

The presentation included a cursory market study that suggested Old Louisville alone would not be able to sustain the business district and increased development on its own. Instead, the plan recommended making Oak Street a destination that would appeal to a wider target market in the larger city.

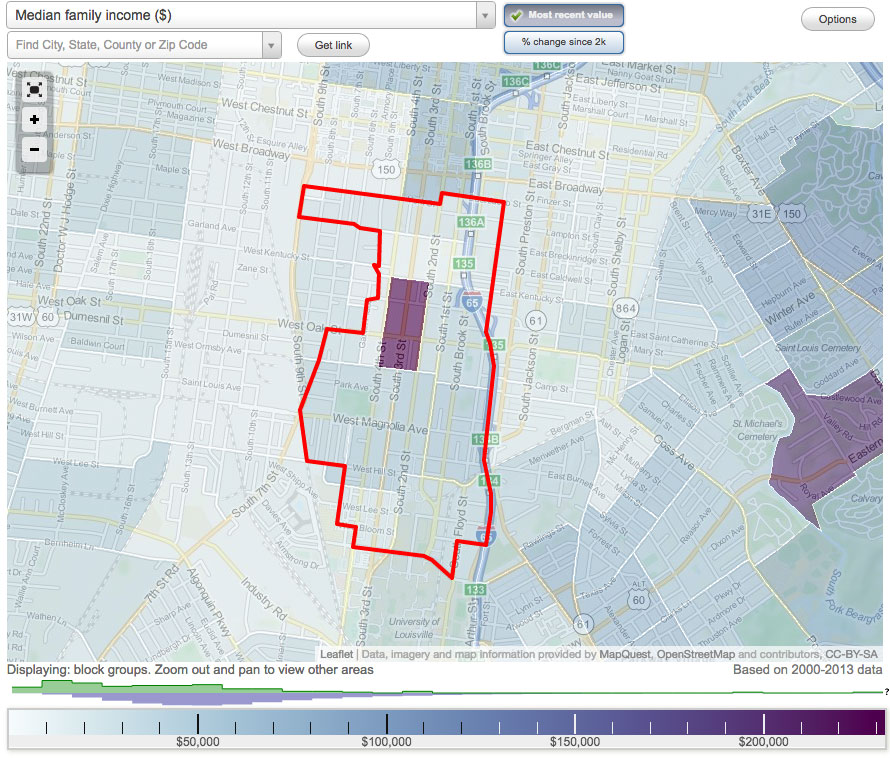

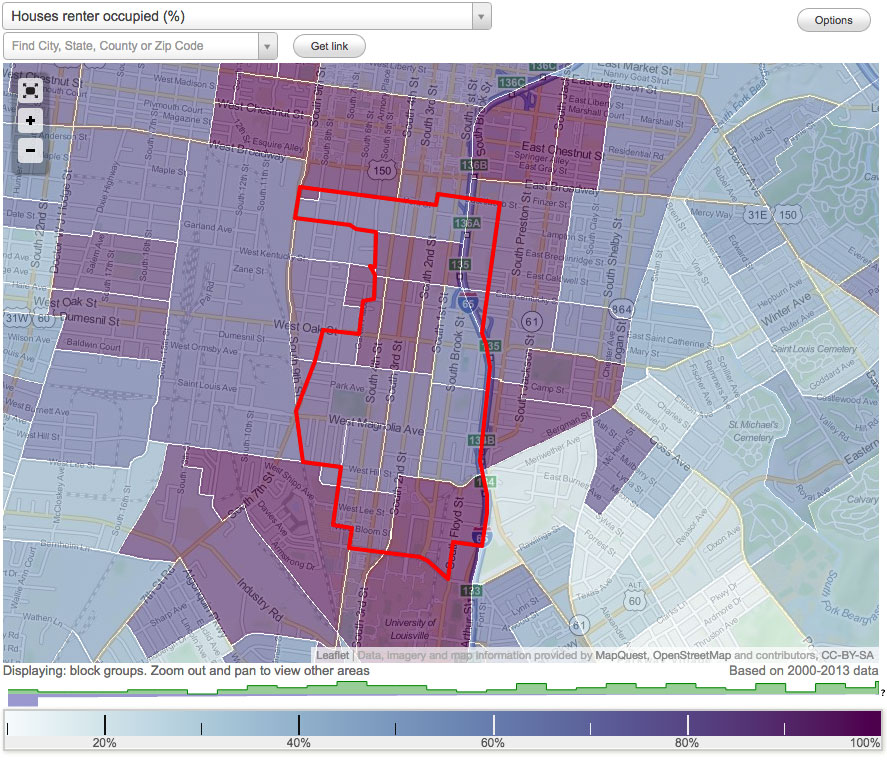

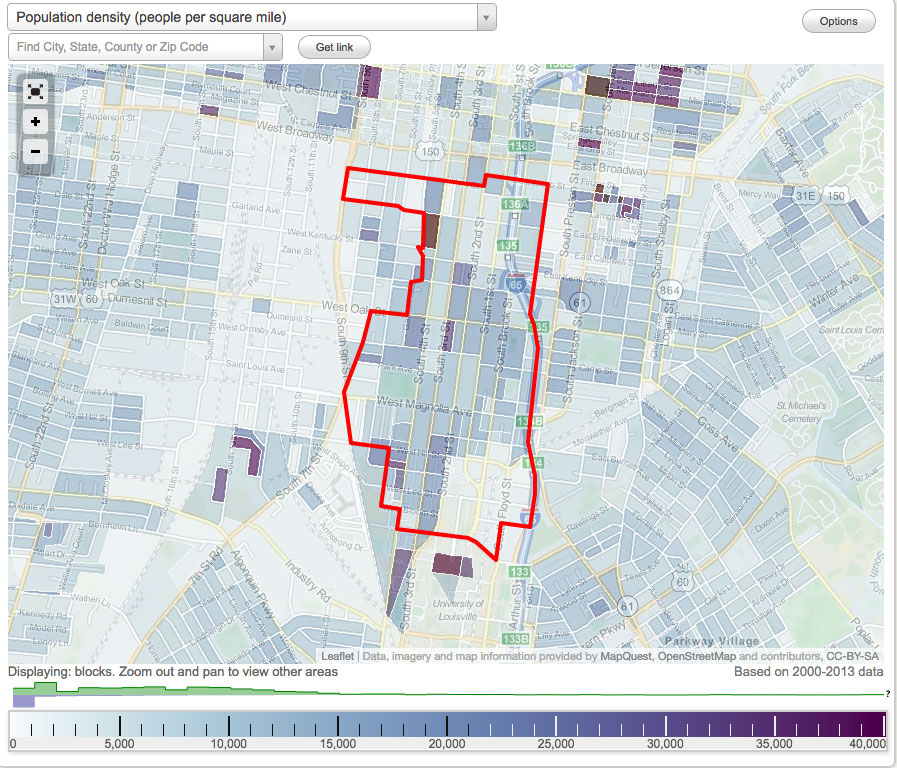

“First, we looked at the market,” the presentation stated. “There is a continuing debate as to whether the Oak Street Corridor market is large enough, dense enough, or affluent enough to support a range of traditional neighborhood retail establishments. This is more of an art than a science, but the immediate trade market, though dense, is somewhat constrained. Most successful commercial corridors show strong demand from each direction, and often sits in the middle of neighborhoods on each side.”

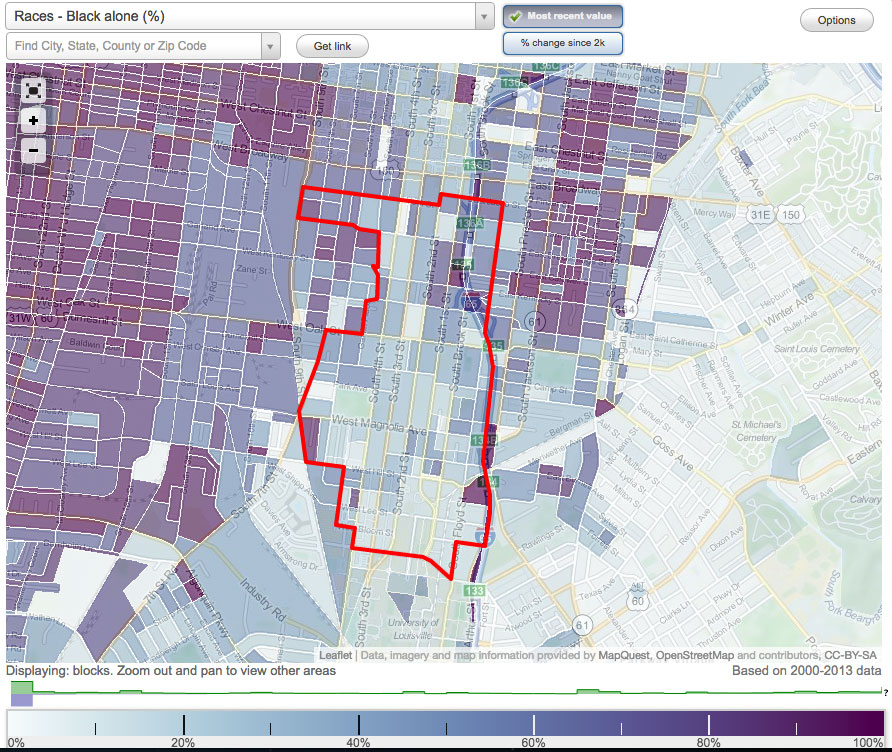

That’s not the case in Old Louisville, where industrial areas to the west, depopulated areas to the north, and poor-but-up-and-coming areas to the east present challenges to local buying power. Only the small area around Central Park and St. James Court was truly wealthy enough to support the kind of development the neighborhood is clamoring for.

This notion arose over and over again in conversations I had with leaders about the vitality of the Oak Street corridor: The market is just not there yet.

“In Old Louisville, the middle class residential component is pretty small,” White said. “There’s no dollars there—people there don’t have much income to spend.”

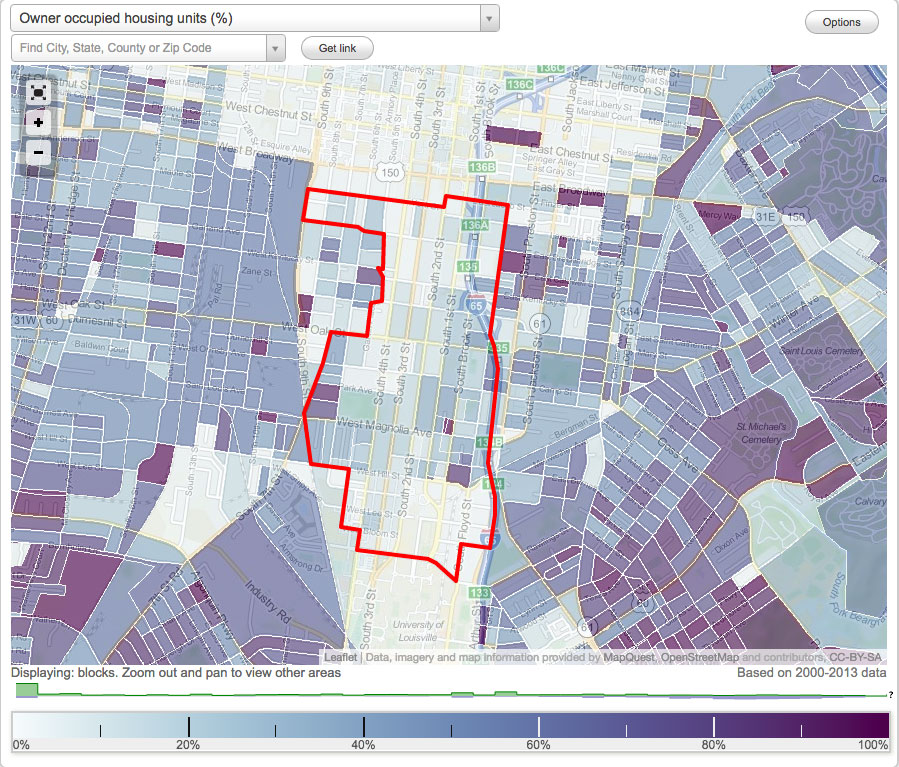

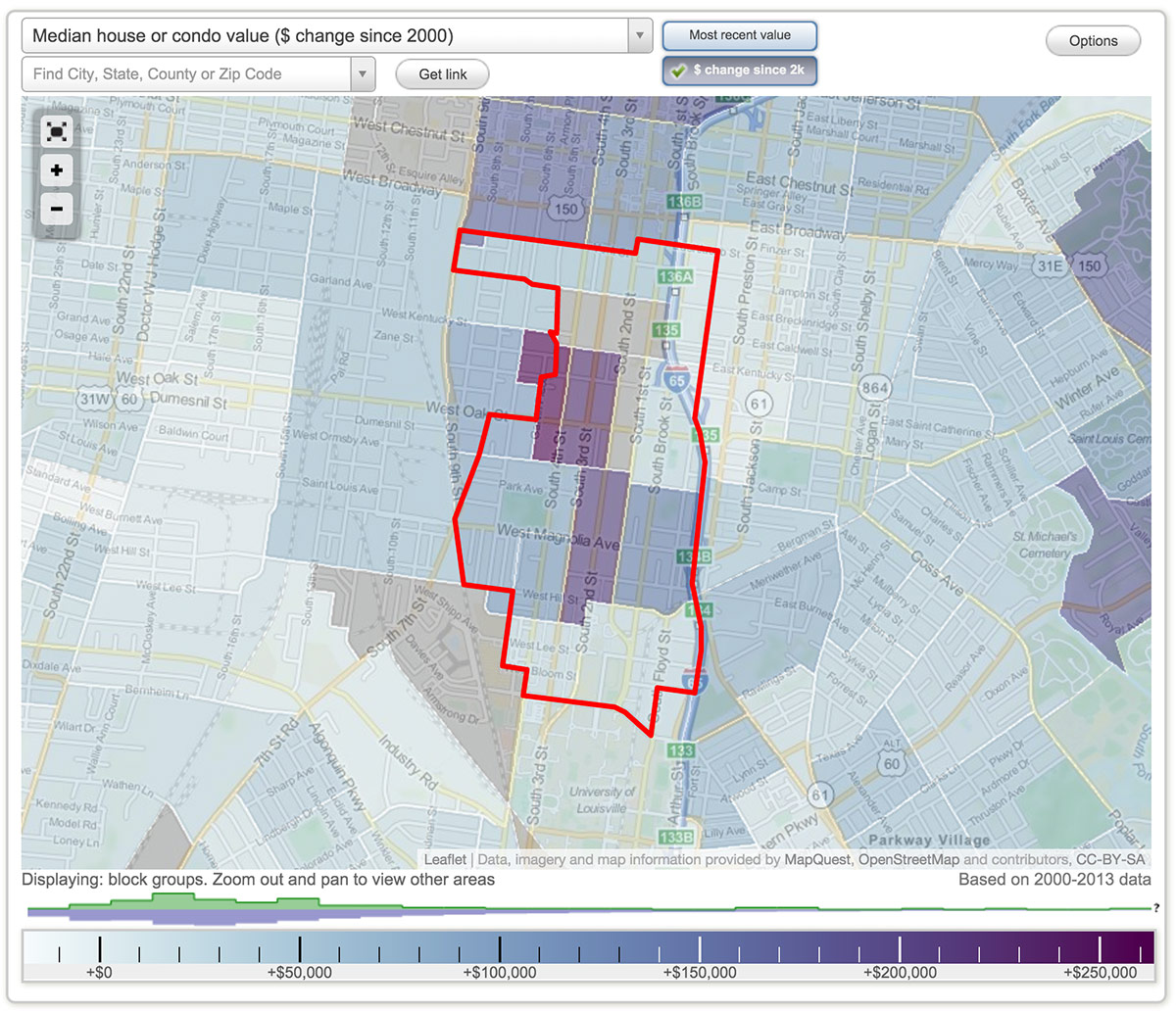

White explained that Old Louisville was hit particularly hard by the economic downtown. “In the 2010 Census, the resident ownership had shrunk to about 15 percent of the total property ownership,” White said. “It had been around 17 percent in 2000 before the Recession and foreclosure crisis.”

“That corridor needs to be jumpstarted,” White admitted, “but I don’t think zoning is the remedy to it.”

For Rosenberg, the data about Oak Street and TNZD is missing, and he doesn’t see any good it has brought about in the past 15 years. “That’s one of my personal issues about the TNZD,” Rosenberg said. “Tell me what has happened in a positive way because of it?”

“If you look at the TNZD since 2002, what studies have been done to look at the effectiveness of the TNZD?” Rosenberg asked. “What has happened? Have occupancy rates or vacancy rates gone down? Has there been a decrease in crime or has it stayed the same? What positive effects have happened? If you can’t answer those questions, why keep something in place? I say it behooves us and the city to look at those factors.”

While there has been no formal study, there’s a lot of information out there that we can use to understand the complex issues facing Oak Street.

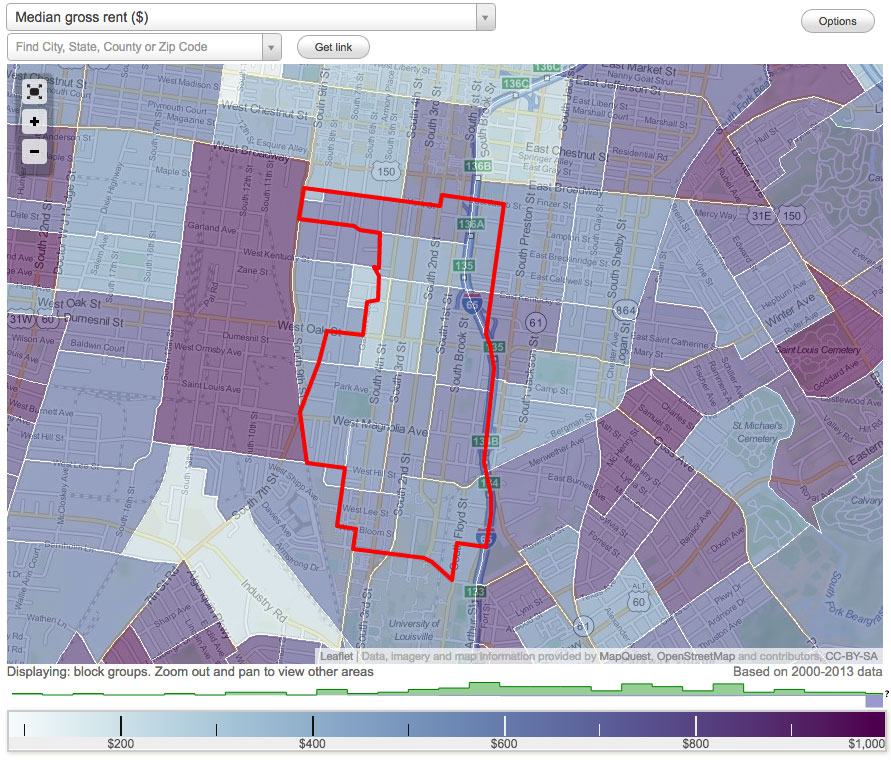

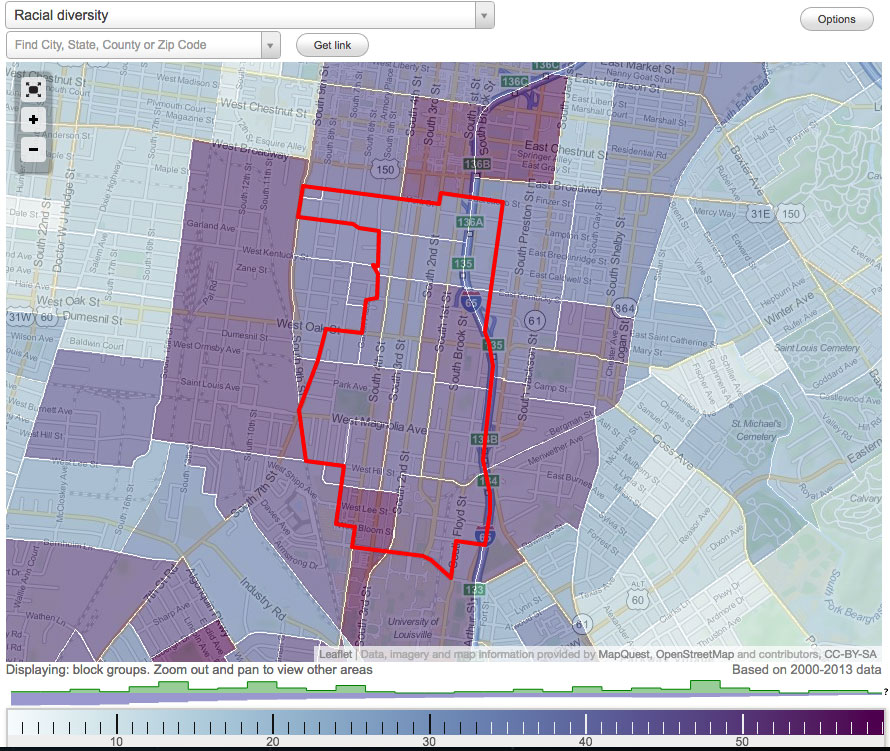

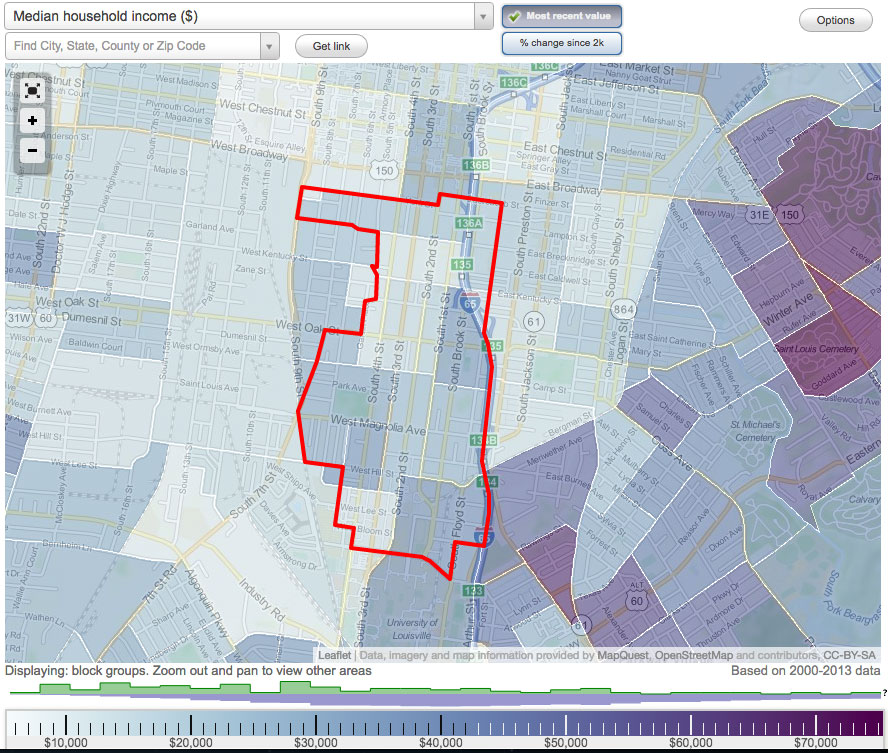

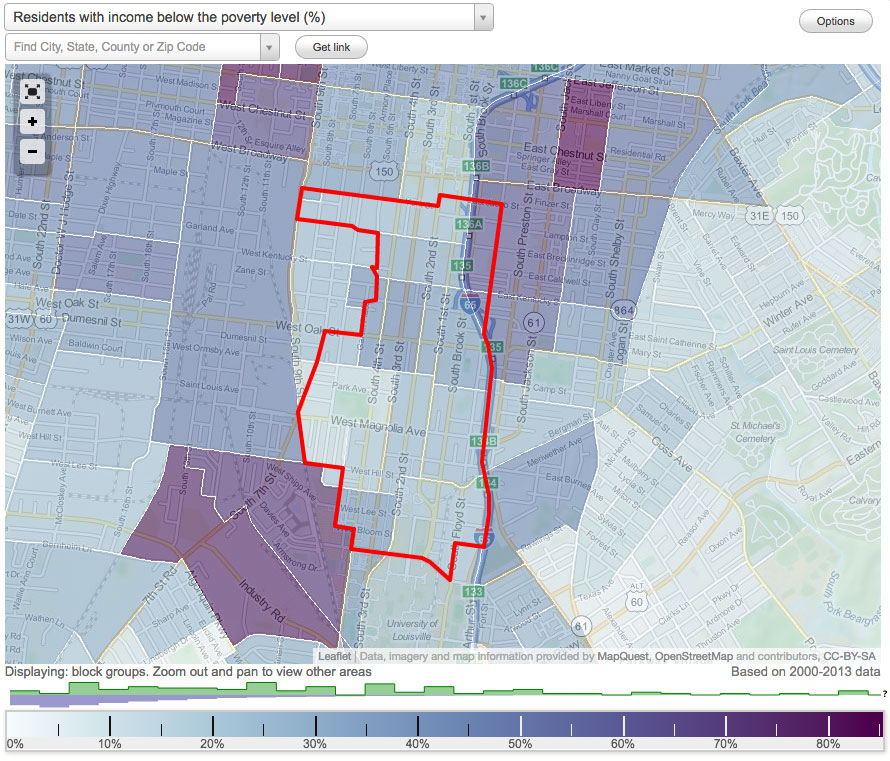

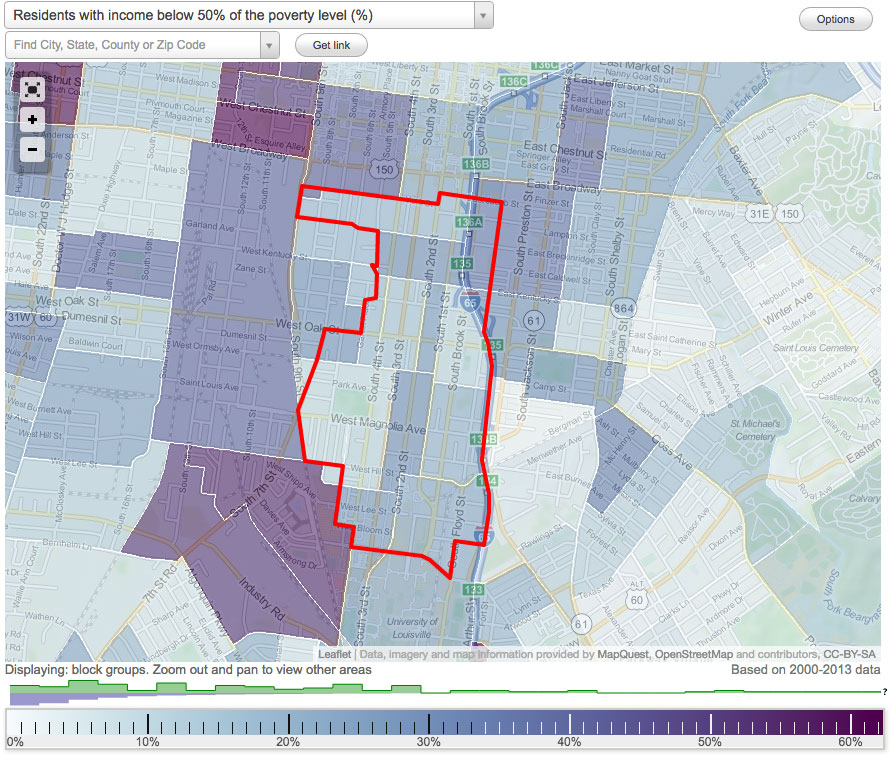

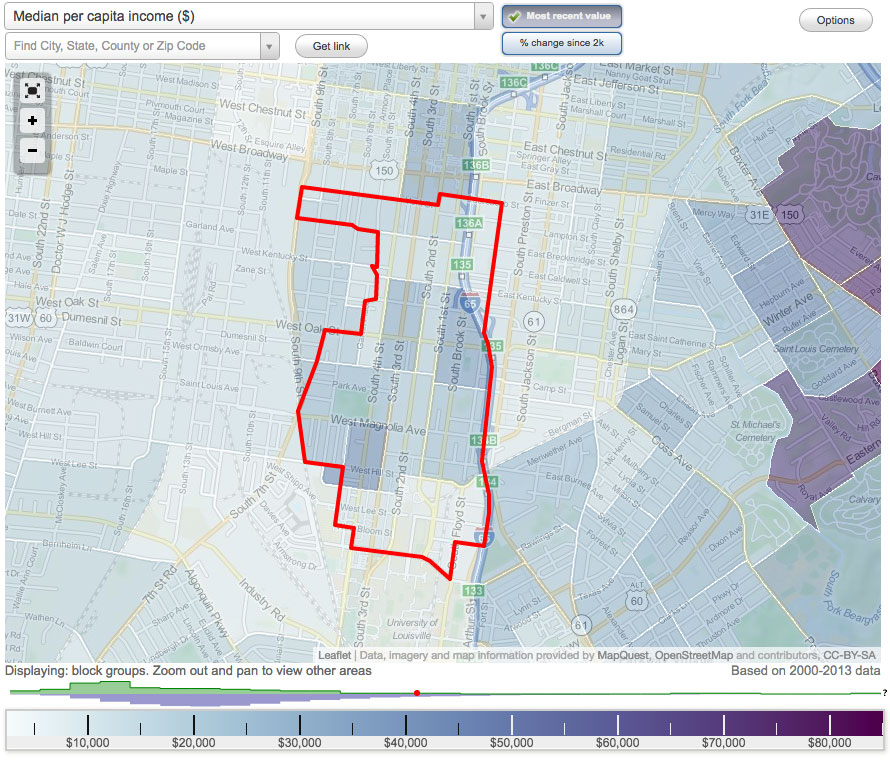

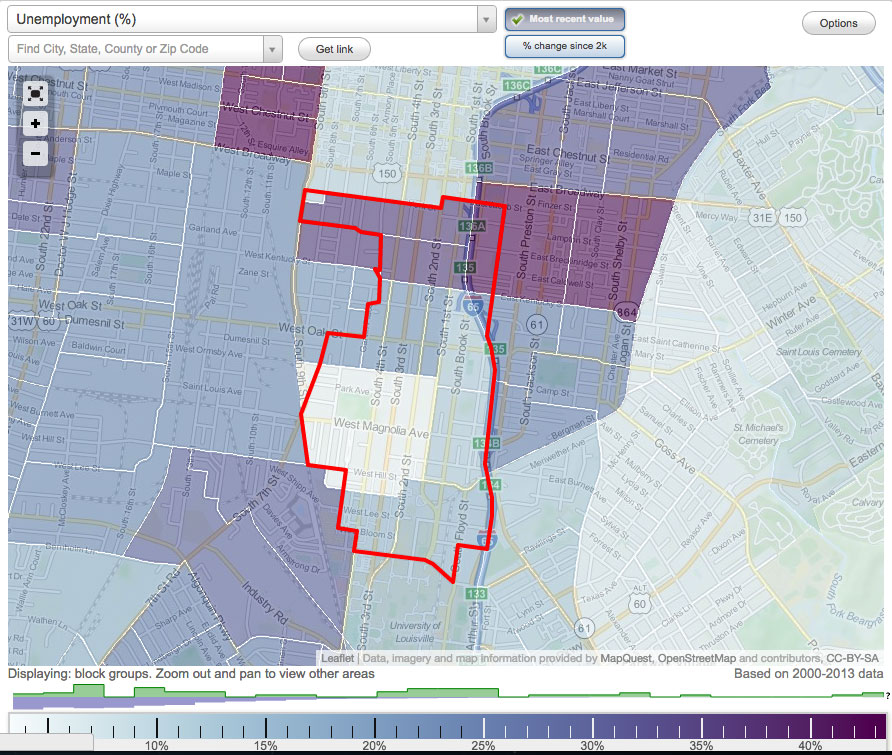

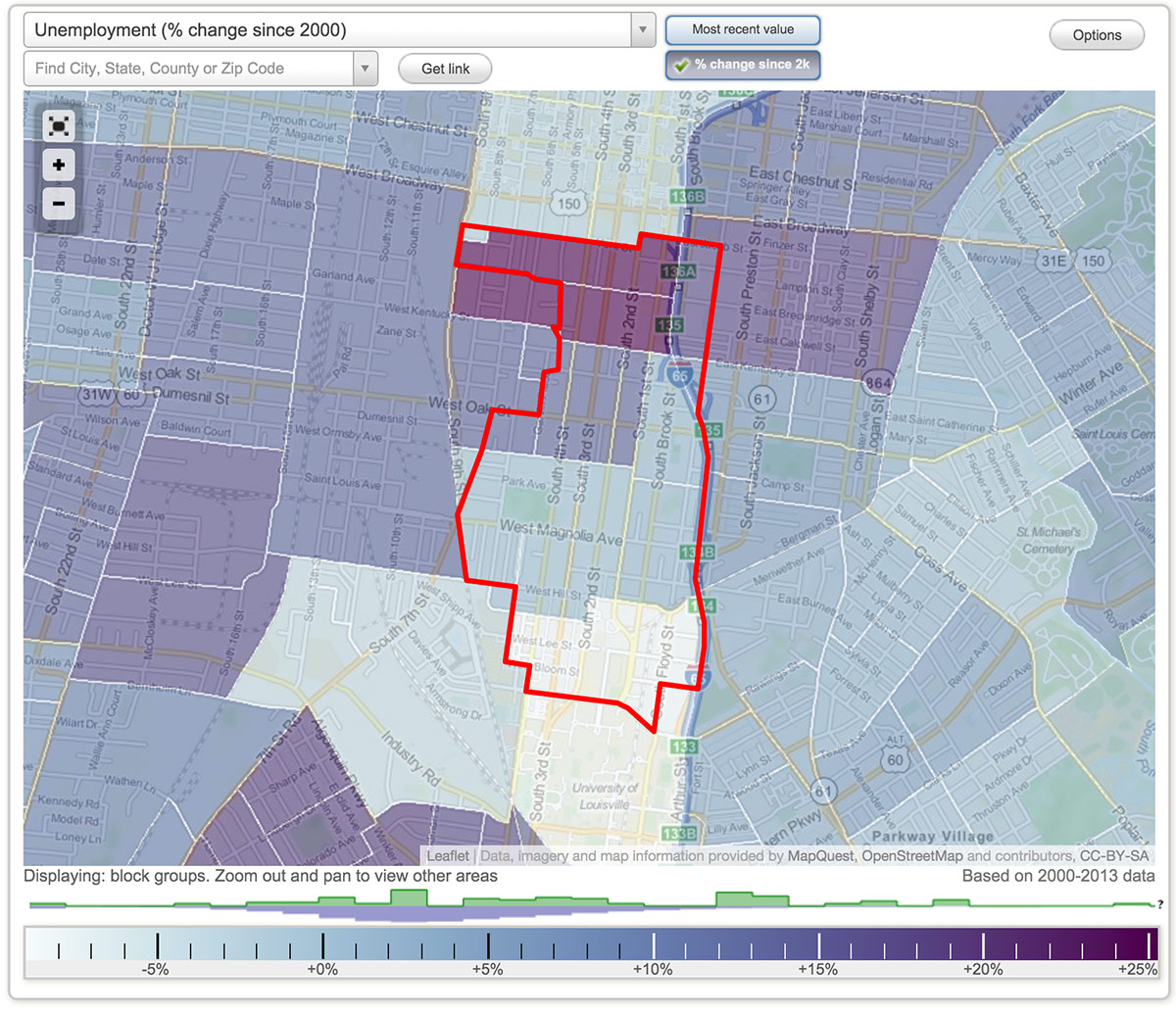

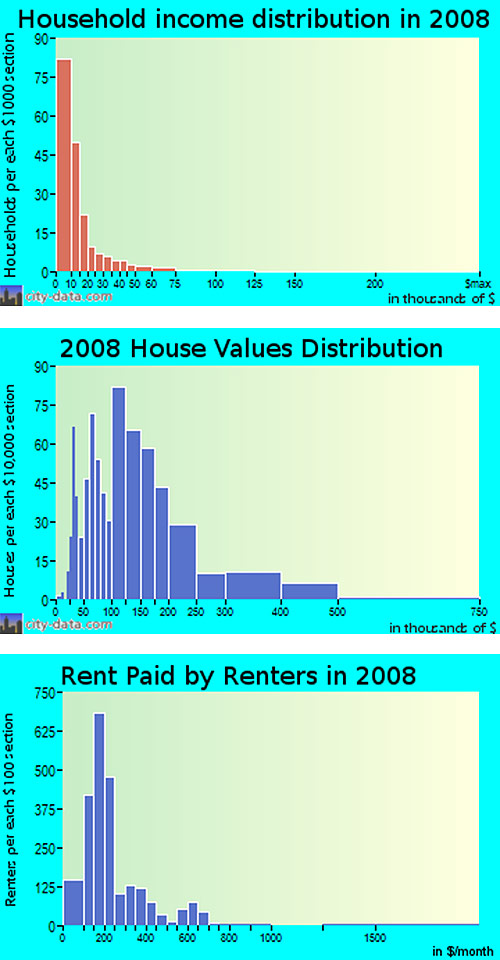

In addition to Alberts’s observations, we looked into a variety of census data from 2013 to try to figure out what’s at play. Flip through the charts above for information about income, population density, unemployment, owner-occupied housing, and more.

According to census-tracking website City-Data, Old Louisville has a circa 2013 population of 10,251 within its 1.19-square-mile bounds, making it about twice as dense as the Louisville average (8,624 people per square miles versus 4,125). That bodes well for the future of the neighborhood’s commercial district, but it’s not enough to say population density alone is a market.

In 2013, Old Louisville’s median household income stood at nearly half the Kentucky average, $22,810 versus $43,399. That’s the lack of spending power the experts are referring to in their analysis.

Further, while much progress has been made converting Old Louisville’s mansions back to single-family homes, the fact remains that many are still carved up into tiny, cheap apartments. The 2013 Old Louisville median rent was only $493 compared to Kentucky’s median of $525.

Heatmaps from Louisville data site Metromapper show that Old Louisville and its surrounding neighborhoods were hit particularly bad in the foreclosure crisis, compounding the problems facing commercial development in the area.

Barry Kornstein, a 24-year resident of Old Louisville and a research manager at the University of Louisville’s Urban Studies Institute, School of Urban & Public Affairs, believes the issue at hand is much more complex than the rezoning and remapping plan suggests. “I believe that the current proposal addresses none of the complex issues, that it is really just a solution looking for a problem put forth originally by a frustrated, but logically challenged group of people,” he wrote in a letter to the city expressing his “extreme opposition” to the changes.

From the data above, it’s clear that Old Louisville is stuck in the middle of some of the larger issues facing all of Louisville today. It’s very diverse because it sits in between almost all-white and all-black parts of town. It’s very poor yet has some of the wealthiest citizens within its bounds. It’s making progress, but that progress has been slow.

“The primary challenge that Old Louisville faces from a commercial development standpoint is that it is essentially an island,” Cash said.

Those frustrated with TNZD are quick to point to Frankfort Avenue, Bardstown Road, and East Market Street as examples of C2 that are seeing healthy development levels. But Cash says there no comparison between those streets and Oak Street.

“Frankfort Avenue and Bardstown Road are the main corridors through densely settled traditional neighborhood patterns on both sides of street for miles,” Cash said. “That’s not true of Oak Street. To the north is a very sparsely settled area called SoBro. There are not many residents there, and not a lot with disposable income. To the east is Smoketown and Shelby Park. While they’re seeing a renaissance, there’s still not a lot of disposable income. If you go a few blocks west, you’re in an industrial area that has seen a huge drop in employment in the last 20 years. Places like the Vogt Machine Company used to have 1,200 people working there.”

And much of Oak Street’s current lineup is home to under-market-rate housing and halfway houses, including a beautiful former church operated as a halfway house by Dismas Charities and two sturdy multi-family buildings at 210-214 West Oak Street (12 units) and 206 West Oak Street (six units) owned by New Directions Housing Corporation.

There is vacancy along the Oak Street corridor, but, again, it’s difficult to tie it to the TNZD. The Winn-Dixie site has been vacant for decades and will require special attention to redevelop. Rumors have been swirling for years that some kind of development there is just around the corner, and those rumors will likely continue for years more.

Browsing the Kentucky Commercial Real Estate Alliance’s (KCREA) website listings shows only five properties for sale or lease in the vicinity (this is by no means the entire list of potentially available properties). Those include a modern brick building in a parking lot at 435 West Oak; the former Rudyard Kipling property at 422 West Oak Street; another modern building behind a parking lot at 218 West Oak; a commercial storefront on an old mansion at 1213 South Fourth Street; and live-work space in a house at 118 West Oak.

These issues are difficult to address and take time to fix. Zoning changes, by comparison, are easy. And now that we know the arguments on both sides, let’s walk through the process that led up to the Planning Commission meeting.

Debate at the Old Louisville Neighborhood Council

To understand where the debate Old Louisville, it’s important to look back at the neighborhood process that got us here. And it’s certainly a complicated one.

The process of changing Old Louisville’s zoning really picks up steam in January 2014 when Howard Rosenberg was elected as chair of the Old Louisville Neighborhood Council (OLNC). Rosenberg told Broken Sidewalk that, while not a business owner himself, among his goals as chair was to give a new voice to the Old Louisville business community.

“When I took the position of chair of the Old Louisville Neighborhood Council, the Old Louisville Chamber of Commerce had become somewhat defunct,” Rosenberg said of the now permanently closed organization. “It’s focus had changed, and there really was no strong voice for business in Old Louisville”

“Rosenberg announced in January that he was going to form a business advisory committee,” Christopher White said.

“Basically I put together a task force made up of mainly business owners in Old Louisville who were also residents of Old Louisville,” Rosenberg said. “Some own properties, some own retail businesses. It’s a mixture of individuals.”

Rosenberg said the group’s intention was to make it easier for people to do business in Old Louisville. “I asked them three questions: what supports business in Old Louisville, what doesn’t, and what do you want to see done,” Rosenberg added. “And out of that came the recommended changes to the TNZD.”

But a preexisting group had been working on the issue of amending the TNZD’s permitted use list for two years before the Business Task Force first convened. The so-called TNZD Review Group, instituted by former OLNC Chair Joan Stewart, had begun work on revising the permitted uses under TNZD. Among the members of that group were White, Bajandas, Councilman David James, Director of Codes & Regulations Jim Mims, and a representative from Mayor Greg Fischer’s office.

By September 2014, when the Business Committee presented its recommendation to rezone the neighborhood to C2, a clash between the two groups working on the same problem from different points of view was all but inevitable.

“The Business Committee issued this very clunky, terribly worded motion,” White said, “that wanted to enlarge commercial uses to match the city’s C2 use list. And they wanted this for all commercially mapped properties.” That included not just Neighborhood Center and Neighborhood Transition-Center, but also Corner Commercial in the residential areas of the neighborhood.

“This launches a real struggle within the council because the Business Task Force really did not allow for discussion of this,” White said. “We got into a long, many-month struggle. Really lots of bad blood.”

A compromise was reached in December 2014 when the Business Task Force agreed to use the TNZD Review Group’s revised TNZD use list for Corner Commercial properties while keeping the other commercially mapped areas C2.

After more debate in January, the issue was formally adopted by the OLNC on February 24, 2015. That new motion, “finely worded with specificity and coherence,” as White described, fit into a concise paragraph. It read:

With that, the stage was set to bring C2 zoning to Old Louisville’s Neighborhood Center and Neighborhood Transition-Center commercial areas. “Those commercial uses would conform to the city’s C2 list of commercial uses, auto lots and all,” White said.

But the story is far from over. Somewhere along the way, what Old Louisville asked for turned into a much larger project, with much greater implications on how the area will develop in the next two decades.

For more on the details of the rezoning motion and the OLNC process, read Christopher White’s account here.

The motion makes its way to City Hall

After the OLNC passed the rezoning motion, that above paragraph was submitted to Councilman James to present to the Metro Council to get the legal process rolling. But what James took to the council on March 24 is distinctly different than the OLNC’s original motion.

James’s resolution took the OLNC’s motion to change the neighborhood’s zoning and added in that Metro Louisville should look at expanding the boundaries of the commercially mapped areas of the neighborhood to include single-family houses along Oak Street.

Resolution Number 040 reads:

A resolution requesting the Planning Commission, through staff in Louisville Metro Planning & Design, to: 1) evaluate the Traditional Neighborhood Zoning District (TNZD) regulations particularly as those regulations relate to signage on properties within the TNZD and the list of land uses currently set forth in the “Traditional Neighborhood Zoning District Plan Report for Old Louisville / Limerick,” appendix 2B of Chapter 2 of the Land Development Code, to determine whether the TN use regulations are effectively achieving the purposes originally outlined in the TNZD Plan and whether expanding the list of land uses to include more commercial uses to promote additional economic development and opportunities is beneficial to the TNZD; 2) examine the current Neighborhood Center boundary on the TNZD plan map to determine whether it should be extended to include properties on its periphery and nearby that have commercial character that would warrant their inclusion in the Neighborhood Center; and 3) hold a public hearing and make recommendations to the Louisville Metro Council based upon the record of evidence established for enumerates requests 1 and 2.

“It was a different resolution. I do not know where it came from,” White said of James’s document. “It was like five pages long and it was the first time anyone expressed the idea of enlarging the mapped boundaries of the commercial components of the neighborhood. It really starts to specify all this stuff that was so far outside the scope of what the neighborhood council voted on.”

How did that disparity in wording happen? “We’ve been looking at that,” Rosenberg said, sounding as confused about its provenance as anyone we spoke with.

White confronted his councilperson about those changes at the April OLNC meeting, asking how his resolution could be so different that what was voted on. “I said, can you explain this since you’re the author of the resolution?”

According to White, James denied writing the resolution, instead directing questions to County Attorney John Baker. “He [James] said he had no idea how that language got in there,” White said. “He said he was not the author of the resolution, which, of course, makes no sense because it’s his resolution.” White said Baker denied altering the resolution.

David James did not return an email requesting comment for this story.

At any rate, the James resolution was adopted with its expanded wording by Metro Council in mid-April 2015 with a unanimous vote.

“Over the last few years, the Oak Street Task Force has tried to promote business growth to blend with residential uses for the area but the old regulations have sometimes complicated those efforts,” a press release from James at the time read.

“It’s startling to see this in the resolution,” White said. “That the resolution stigmatizes the TNZD as possibly being a retardant to development in the neighborhood.”

“We only ask that a serious evaluation be done to determine if there is flexibility in the regulations and whether or not the time has come to reposition the boundaries in the original plan,” James said in the press release.

With the resolution passed, Metro Louisville Planning & Design Services staff began to tackle the issue, scheduling three public meetings to discuss the changes. The first meeting at the Old Louisville Information Center, a simple question and answer session, took place in July 2015. Then the controversy again started to heat up again at the second meeting in August.

“They came up with some solid recommendations,” Bajandas said of the August meeting. “But they were met with such resistance [from the neighborhood] they had to go away and it took them until January—five months later—to come back with a version of what was done at the August 11 meeting.”

“It was an embarrassment for me to watch these planning staffers squirming, because in this neighborhood people feel so strongly about things,” White said. “And people just attacked them up and down and back and forth.”

By January 2016, planning staff were ready to present their final report. “In January 2016, the staff comes back for another public hearing, and they have further expanded things,” White said. “They have introduced entirely novel ideas that nobody ever discussed in the neighborhood—no association has been able to vote on these—and these have been promoted now to the Planning Commission and they had no neighborhood input.”

But while those who initially opposed the rezoning urged caution, others, especially the neighborhood’s business interests, were strongly in favor of the expanded scope.

“I think it’s a prudent thing to do,” Rosenberg said, comparing the process to a doctors visit, where the whole body is examined, not just a portion displaying symptoms. “Here’s my take on it. I think any time you propose something, there’s a process within the city to look at it, and in this case it’s Planning & Design that eventually looked at it,” Rosenberg said. “I think they have an obligation to look at the whole… To say, okay, you’ve asked for this but we want to see what’s the impact if this is done? Should other things be done? Are there changes that ought to be made in line with this? If we’re going to take one part of the TNZD and change the permitted use list, what else should we be doing at this time?”

“Where it started, and how it came about? I have to assume it’s because when looking at it, people believe it’s time to look at the whole thing,” Rosenberg said. “I don’t find that disheartening. This to me is part of a normal process.”

But for others who worked for years at the neighborhood level for a hard-fought consensus, they find it unfortunate these changes were born out of backroom talks and resolution drafting rather than the public process.

What will happen under the changes?

If Old Louisville is rezoned C2 and the mapped commercial area is expanded as will be discussed at the upcoming Planning Commission meeting, there remains a lot of uncertainty about how those changes will play out in the historic neighborhood.

“So what’s going to happen with these changes, if they are implemented uncritically and without any kind of change, is extreme conflict between zoning and landmarks,” White said. “The TNZD worked with historical preservation to create zoning that facilitated preservation and protected it. What we’re going to have now is a conflict, and, as far as I’m concerned, the victim of the fallout is going to be a real debilitation of landmarks.

“When zoning and landmarks come into conflict, I predict that zoning will win out,” White added. “Landmarks is already hardly the agency it once was in terms of enforcement. But they’re going to be even more denuded under this.”

But Rosenberg doesn’t see a conflict.

“Keep in mind we’re sitting in a historic district. These structures are protected by Landmarks, which in many cases is a lot stricter in terms of what you can do to a building,” Rosenberg said. “I can’t take my house and destroy the facade and put in a big plate glass window and put in a barbershop. So we’re limited by the structures themselves. But within these structures and within the commercial zone, we want to make it easier for businesses to be able to come in here. It doesn’t mean there won’t be certain restrictions that are still governed by zoning, but this is changing the permitted use list within the TNZD to make it more flexible.”

“The Landmarks commission is a lot more strict than the TNZD in terms of structure,” Rosenberg said. “This is my understanding. You cannot alter the structure. I have certain restrictions in terms of my windows and Landmarks is going to take precedence in those decisions. Regardless of what the zoning is, it’s still a landmarks district.”

But Cash believes problems could arise. “State law that enables historic preservation districts specifically says that zoning is zoning and design review is design review,” Cash explained, citing KRS 82.670. “If use allows something, design review can’t take the use away. It doesn’t matter if design review doesn’t like something.” In other words, if a gas station is proposed, design review can’t turn the project down as it already is permitted under the C2 zoning.

“You’re putting the two processes at total odds with one another,” Cash continued. “People that say Landmarks will protect it have never tried to put a McDonalds or a Thorntons in a historic district. I know what it takes. You can’t make it work—not very well. By the time everything is accounted for, you wipe out a city block.”

And that’s a scenario that could play out under C2 zoning. Gas stations, car lots, and drive-thrus are all permitted under C2 zoning while they have been prohibited under TNZD. Could we see a gas station on the corner of Fourth and Oak streets? “Yes. Under these changes we could,” White said. “And then we’ll see Kroger move in to Fourth and Oak with a suburban style layout.”

Again, Rosenberg defended the changes. “If you look at the vacant properties and vacant lots, that’s pretty much not going to happen,” he speculated. “But if you look at Bardstown Road, there’s a car rental place on Bardstown Road that’s very unobtrusive.”

Rosenberg even seemed okay with the notion of car service stations and gas stations setting up shop along the historic corridor, noting that a gas station once stood in the front yard of a house at Sixth and Oak streets near where he lives today. “Why should I have to drive all the way across town to get my car serviced?” he questioned.

Others supporting the change agree with Rosenberg. “If there was a vacant lot somewhere, I wouldn’t be opposed to an auto lot,” Parets said. “But I don’t foresee that happening. Ultimately, the free market will give us what’s best for the community. I don’t think a gas station is worth it.”

“You have to assume the people that are opening up businesses are smart enough to know they’re going to put a business in that’s going to be successful,” Rosenberg said.

What happens next?

The crucial next step is a meeting of the Louisville Metro Planning Commission. That meeting, open to the public, takes place on Monday, March 21 at 6:00p.m. at the Old Jail Building, 514 West Liberty Street. You should attend.

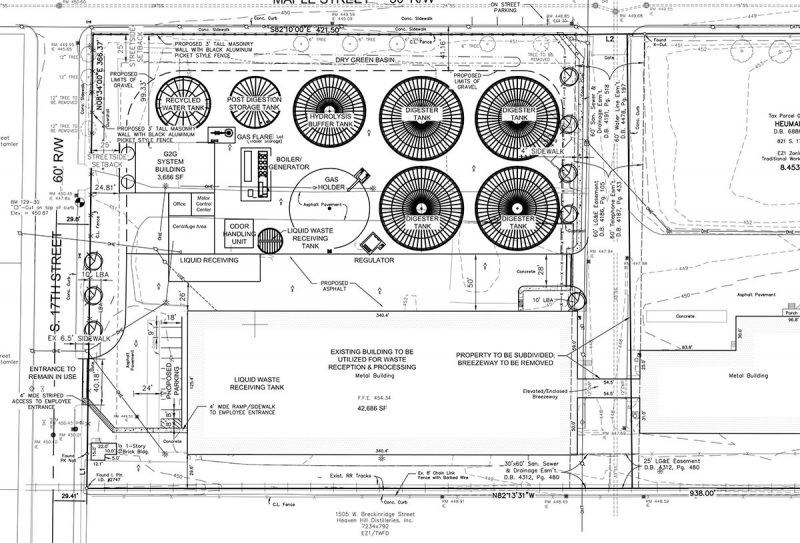

The latest Planning Commission Staff report, dated March 21, 2016, backs off an earlier plan to remap Oak Street to commercial zones from First Street to Floyd Street, but keeps the westward remapping in place (see map). “If the amendments currently under consideration contribute to increased commercial activity along Oak Street in the future, then at a later date the eastern portion of Oak could be considered for a change in neighborhood type,” the staff report states.

“20 properties are considered under this change to the TNZD Zoning Map,” the staff report reads. That’s down from over 50 properties that would have been affected under an earlier staff report from January. “Three properties are proposed to be changed from Neighborhood General to Neighborhood Center. Fifteen properties are proposed to be changed from Neighborhood General to Neighborhood Transition-Center. Two properties are proposed to be changed from Neighborhood General to Neighborhood Center Transition: Edge Transition.”

“If approved, the proposed map amendment would have the effect of making a wider variety of commercial uses available to the subject properties,” the staff report reads. “All current applicable standards of the Land Development Code and all Old Louisville / Limerick design review provisions remain in effect.”

Additionally, the staff recommendation backs away from the Business Task Force’s desire for a full C2 list of uses, eliminating three C2 uses in the Neighborhood Center and TK in the Neighborhood Transition-Center, while adding back in several uses that are permitted under TNZD but not C2.

“Staff recommends that the permitted uses for the Neighborhood Center neighborhood type, focused at S. 4 Street and W. Oak Street, be the same as the permitted uses for the C-2 zoning district,” the report states, “with the only exclusions being those uses that could be most detrimental to the character the TNZD promotes and maintains: stand-alone automobile parking areas, automobile rental agencies and automobile sales agencies.”

Regarding Neighborhood Transition-Center, the staff report recommends that the permitted use list “be the same as the permitted uses for the C-2 zoning district, with exclusions related to auto- and boat-oriented uses.”

The report also recommends representing a commercial area along Seventh Street differently on the map to avoid confusion. You can read the full staff report here.

In the end, the staff recommendation is not the same as what the OLNC motion asked for, and it is not the removal of TNZD from Old Louisville. The report suggests something in between what those for change and those against the change in terms of zoning. Old Louisville will still have a list that’s “something other than C2” just like it did before, even though it’s now a lot closer to straight up C2. And it still, nonetheless, means a gas station is a permitted use at Fourth and Oak streets.

We’ve gone over both sides of the debate, the history and significance of TNZD, the history and present conditions along the Oak Street corridor, chronicled the process that brought us here, and presented the city’s recommended changes. That’s a lot of information, and you should be able to make an informed decision about the future of TNZD and Oak Street. We hope the Planning Commission gives the issue before them due scrutiny, as well.

“TNZD is a complicated document, and people’s eyes just roll back into their sockets when people start talking about it,” White said.

In what’s the most important ruling so far this year, the Planning Commission will deliberate three proposed changes in Old Louisville: signage as it related to TNZD regulations (a topic not addressed here); The list of land uses currently set forth in the TNZD Plan Report to determine effectiveness in meeting TNZD goals; and the current Neighborhood Center boundary on the TNZD Plan Map to determine whether it should be extended. It’s those latter two that warrant special attention.

Three of the commissioners are new to the panel and a bit green when it comes to high profile cases like we saw last year with Omni, Walmart, and Kindred, among others. Marilyn Lewis began her post on the commission at the end of last July, Robert Peterson joined up at the beginning of February, and Lula Howard only began her role on March 14. The rest of the commission is comprised of Chair Donnie Blake, Vice Chair Vince Jarboe, Chip White, Clifford Turner, David Tomes, Jeff Brown, and Robert Kirchdorfer.

Depending on how the Planning Commission rules, the plan will then head to the full Metro Council for a final vote.

[Historic photos couriest UL Photo Archives – Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference, Reference.]

[Correction: March 17, 5:00p.m.: A previous version of this article misstated the final staff recommendation on zoning. The article should have stated the recommendation is to amend the Old Louisville TNZD list with the majority of C2 uses but with some exceptions and additions. The article has been corrected.]