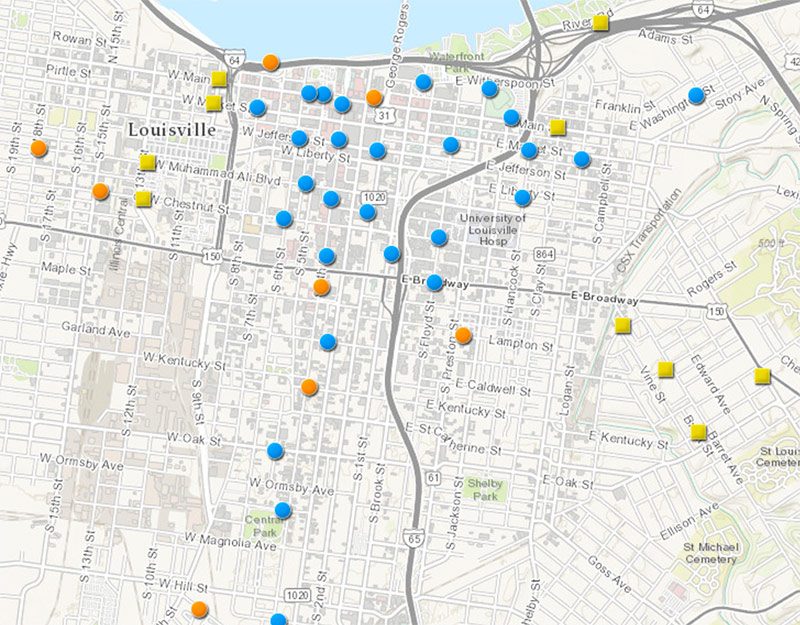

A couple weeks ago, we took a look at the public art installation to be built beneath the Ninth Street interchange of Interstate 64. Designed by a team led by Philadelphia’s Interface Studio Architecture (ISA), The Louisville Knot seeks to draw people to the forlorn block with hopes of convincing locals that the Ninth Street Divide is little more than a several-thousand-ton mess of steel, concrete, and bad city planning. Read more about the Louisville Knot as explained by ISA principal Brian Phillips in our previous article.

While we were talking with Phillips about the Knot, our conversation naturally flowed to cities and the modern role of Tactical Urbanism now that the concept has been embraced the world over (and particularly in Phillips’s Philadelphia) for providing quick, testable solutions that can lead to long-term change.

“I think what we’ve learned about the 21st century American city is that the city is this place for creativity and entrepreneurship and food and coffee and rock bands,” Phillips said. “Authentic, genuine, non-franchise things. I think that’s really what’s driven the kind of millennial rediscovery of the city.”

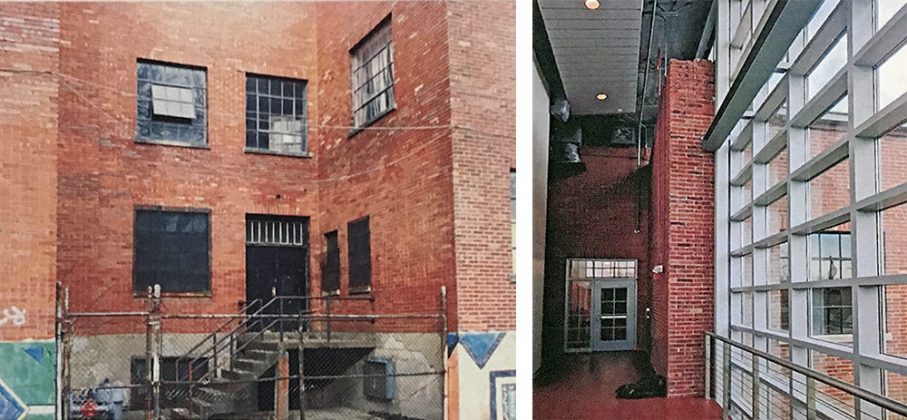

“Those things do not require big, expensive buildings to produce,” he continued. “They require a range of things from temporary to permanent. It requires new housing, and it does require new architectural space. But it also requires renovating buildings in ways that sometimes they still feel a little broken and extra cool.”

“We see that as a continuum,” he said. “We’re moving from a moment where tactical urbanism was seen as a cheap way to get something started to actually a fundamental way of thinking about civic space.”

That shift—and the acceptance of local governments to experiment—is helping to re-imagine street design, public spaces, and how we live in the city. While there was a trend toward experimentation present in the 1960s and ’70s, with groups locally like the Arts in Louisville House or attempts to pedestrianize Guthrie Street, the 1980s and ’90s brought more corporate architecture that often left streets feeling cold. Phillips said cities have finally learned it can be done differently. “It doesn’t have to be hundreds of millions of dollars of polished granite,” he said. “In fact, sometimes that actually sends a message that’s less inviting than when things are done more informally.”

“There’s all this opportunity for experimentation. What we’re realizing is these things apply to so many cities now.”