The first meeting of the year for the Downtown Development Review Overlay (DDRO) committee takes place this Wednesday, January 6 (details below). There’s only one item on the agenda: the demolition of a non-historic auto-shop on First Street to make way for a parking lot.

We wrote about the plan last October, but the DDRO is just now taking up the case.

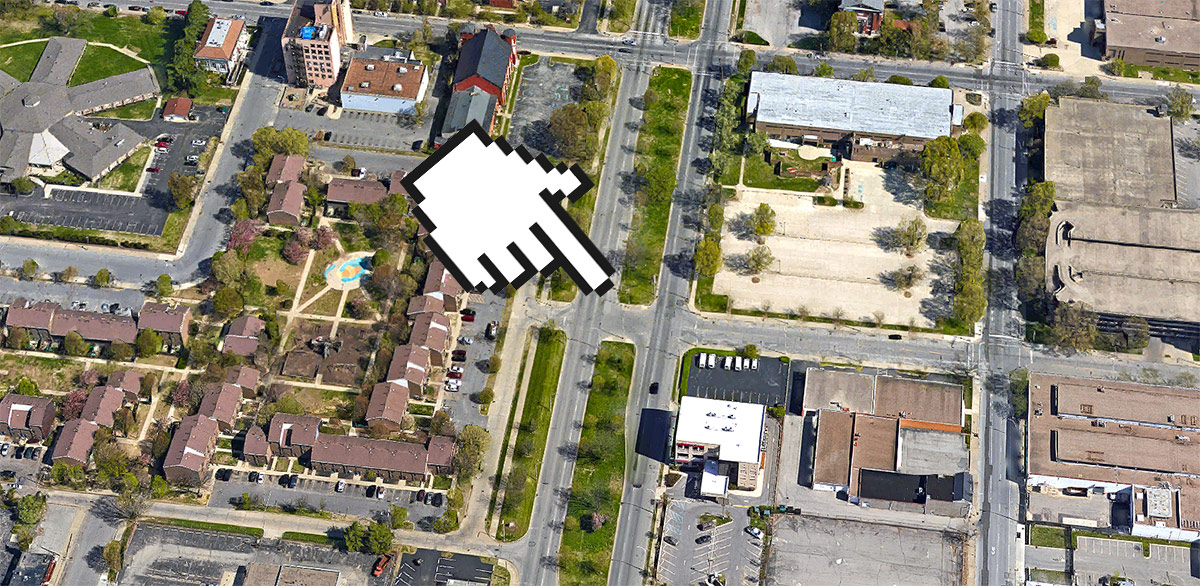

Located on a block already pocked by surface parking lots and dominated by an onramp to Interstate 65, the plan would add 46 new parking spots on the .4 acre site at 430 South First Street. A single-story, 3,439-square-foot former Midas automobile repair shop built in 1975 occupies less than half the parcel today.

The parking lot would serve the adjacent First Urology at 444 South First Street, which already has a parking lot for approximately 38 cars. There are already around 25 parking spots on the auto repair shop site with plenty more in street parking in the area.

According to documents filed with the city, the parking lot would sit behind a seven-foot-tall masonry wall covered in EIFS or stucco built along First Street and along the north lot line. A locked gate would allow vehicular access. As worded in city documents, the wall would be placed directly along the property line with landscaping only on the inside. (No site plan was immediately available.) An existing curb cut will remain from the Midas parking lot, but it would be gated.

First Urology owner Michael O’Shannon and applicant Marv Blomquist of Blomquist Design Group met with city officials last year to discuss the project, according to the city’s staff report. At those meetings, the report indicates discussions included ideas to keep the existing building, but the owner did not wish to maintain the structure.

Ultimately, the staff report recommends demolishing the Midas structure and paving the parking lot. “Although demolition of an existing building for the development of new surface parking is discouraged (Principle 1 SP3 and Principle 5 P3), there are other considerations in this case,” the staff report reads. “The Midas building has been vacant for several years and is of such a small size and specific design that re-use or renovation is not useful for the applicant.”

If you’d like to attend the DDRO’s public meeting on Wednesday, January 6, head over to the Old Jail Building Auditorium, 514 West Liberty Street at 8:30a.m.

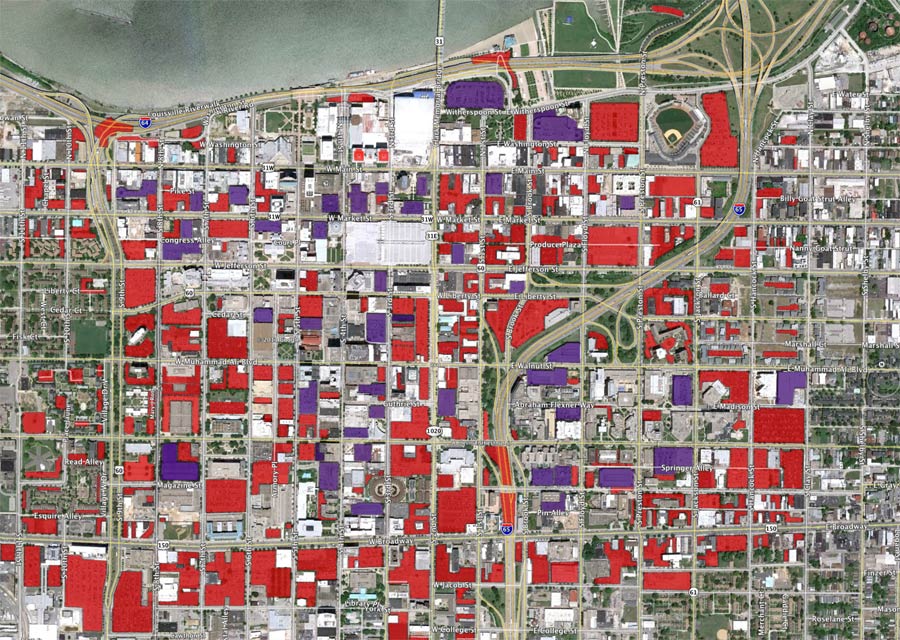

The report goes on to note that, despite the recommended approval, this parking lot use is not what the Overlay envisions for the area. “Eventually the Overlay envisions a fully developed urban context for the entire overlay district,” the staff report reads, “but in this specific edge condition the street wall is ill defined and approximately 50% parking lots.”

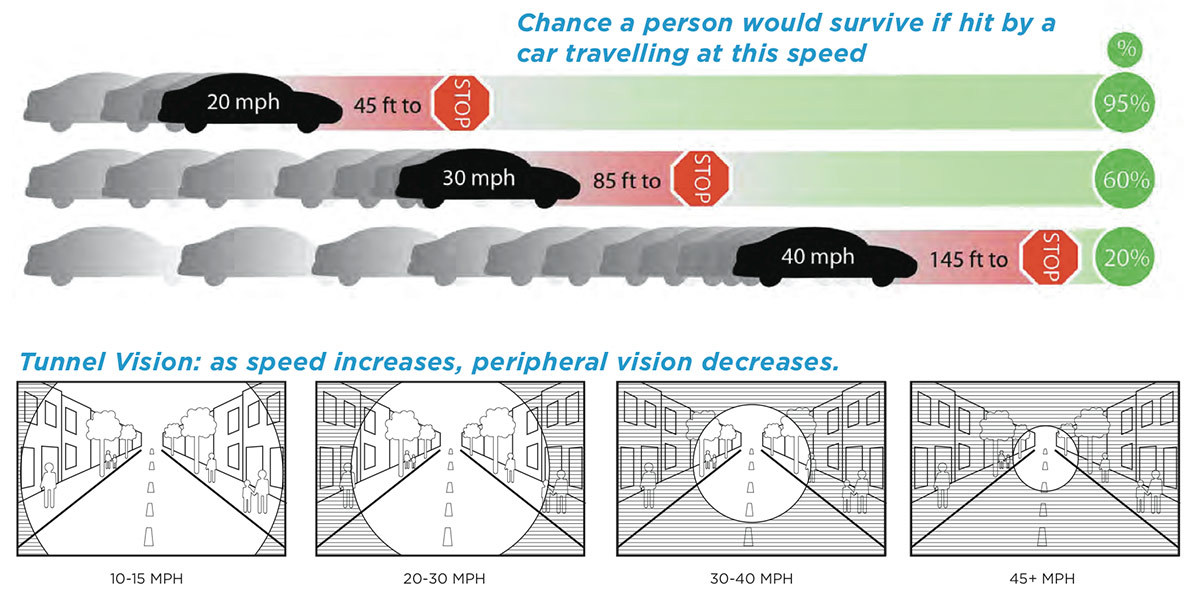

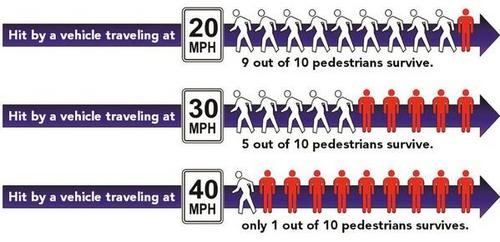

As history has shown, it’s often difficult to unpave a parking lot once it’s in place, so that urban context is likely very far off. Despite a less-than-ideal context of buildings separated by parking lots, allowing developers to pave even more out of convenience will ensure First Street is a suburban speedway for another generation. And that’s to say nothing of the city’s overwhelming heat island effect problem exacerbated by surface parking that landed it as the nation’s worst.

The staff report includes recommendations that the wall is redesigned with better materials and reduced to four feet to increase aesthetics along the street; that lighting and street trees comply with existing standards; and that the applicant consider adding benches or bike racks along the sidewalk.

Looking back at the past year of downtown development review, it’s clear that our process needs a little work. 2015 saw several major decisions from planning staff and the DDRO commission, most notably the contentious issues surrounding the design of the Omni Hotel & Residences and demolition of the old Water Company headquarters on Third Street that played out last July.

There were other important decisions made by the DDRO in 2015 that advance a questionable picture of the future of Downtown. It’s hard to point at Omni as the odd one out when it follows in a line of similar decisions across Downtown.

Back in October 2014, the DDRO approved 14DDRO1012, a project to build the six-story J.D. Nichols Campus for Innovation & Entrepreneurship Parking Garage Structure on the corner of Preston Street and Jefferson Street. That project, still under construction in the shadow of a massive Interstate 65, brings over 800 parking spaces and a dead street wall. But hey, it’s got bike racks located hundreds of feet from anything useful.

In March 2015, the DDRO approved 15DDRO1001, the expanded headquarters of Kindred Healthcare at Fourth Street and Broadway, which we’ve covered a number of times. That decision allowed the demolition of Theater Square for a generic suburban office building set far away from the street behind a less-than-overwhelming new park called Kindred Square. That vote compromising the urban context in the area. There’s space for a restaurant, but that’s not a lot considering how much retail potential was there before.

In June, the DDRO pushed forward 15DDRO1010, a plan to rebuild a Thornton’s gas station at First Street and Broadway. While it was replacing an existing gas station, the urban design of the prominent corner remains fundamentally eroded by the built form allowed to proceed on the site.

One decision didn’t make it to the DDRO committee at all was the conversion of the Kurfees Paint Company building into mini-storage. That project highlights another way projects can be approved Downtown: with only staff approval. The mini-storage project was approved by staff on July 22, 2015 with no retail planned to activate the street wall. We covered that project over here.

For all the talk over creating a deadened Third Street brought about by a loading dock and parking garage, this sort of thing has become routine. To the casual observer, the DDRO has become a rubber stamping panel that, at most, asks for window dressing on projects that put no windows on the street.

This issue is bigger than any of these individual projects discussed here. As we begin a new year, it’s time to ask ourselves important questions. What is the public review process for? What kind of city do we want to build and live in?

We’ve already got a great set of guidelines already built into the city’s land development codes—it’s time we uphold them rather than kick the can down the road. In 2016, it’s time to send bad urban planning back to the drawing board and read up on good city building. Louisville deserves it.