This year, Broken Sidewalk asked each Metro Council candidate to respond to a survey of questions related to the topics we cover here on the site: urbanism, transportation, health, and the environment. Broken Sidewalk will make no endorsements this year for Metro Council candidates, but we hope these survey responses—published verbatim—are helpful to voters in making up their minds.

We will be publishing the results by district. First up is District 4. Our survey included two types of questions: 1. multiple choice answers about personal behaviors and views, and 2. longer responses on a range of topics. Each candidate was also given an optional open field to expand upon a topic of their choosing, if they so desired.

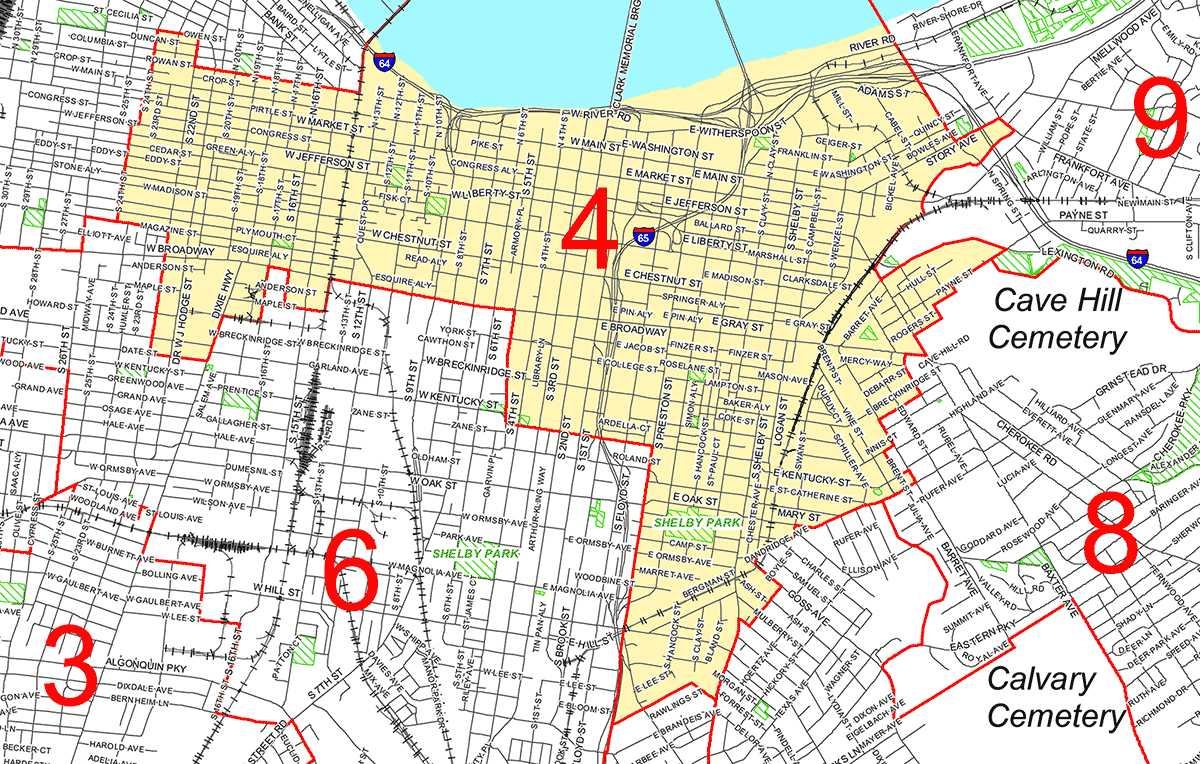

Louisville Metro Council District Four comprises Downtown Louisville along with key core neighborhoods of Russell, Butchertown, Nulu, Phoenix Hill, Smoketown, Shelby Park, Meriwether, and parts of Irish Hill, SoBro, California, and Portland. This is one important district.

Current District 4 incumbent, David Tandy, has decided not to run, so change is coming to the leadership of Louisville’s urban neighborhoods. The candidates for District 4 include, in alphabetical order, community advocate and former Tandy staffer Bryan Burns (D), JCPS employee Aletha Fields (D), Beecher Terrace Resident Council president Marshall Gazaway (D), and former Fund for the Arts president Barbara Sexton Smith (D).

Bryan Burns

Shelby Park

Have often do you walk to work or for basic errands?

Every day

Have often do you take transit to commute to work or for basic errands?

A few times a month

How often do you ride a bike to get to work or for errands?

A few times a month

How often do you drive in a personal motor vehicle?

A few times a month

How safe do you feel as a pedestrian walking on Louisville’s streets?

There’s some risk

Louisville’s transit system should expand service, infrastructure, and offerings.

Strongly Agree

The city should invest in complete street design that promotes safety for all road users.

Strongly Agree

Walkable and transit-oriented development should be promoted over auto-oriented development.

Strongly Agree

Louisville should repair and maintain its existing transportation network before widening or building new roads.

Strongly Agree

Historic architecture promotes the economic vitality of the Louisville region.

Strongly Agree

Describe your favorite walk OR your favorite place to hang out in your neighborhood.

From my home on Camp street, my absolute favorite place to walk is down Logan street, where I can either head to Smoketown USA in the day, or T. Eddie’s for karaoke at night.

What’s the biggest issue facing your district and how would you address it?

What I see as the biggest issue in District 4 is the lack of a solid foundation for our neighborhoods and families to thrive. Many of our neighborhoods suffer from a glut of vacant homes and our entire city suffers from individuals and families who live in substandard or absolutely no housing.

For our neighborhoods to flourish, we need to make sure our current and future generations have multiple and positive opportunities so that they can reach their fullest potential.

In three sentences, what does Metro Council do?

The Metro Council should be both a legislator, facilitator, and advocate for an equitable and healthy development of our city. Louisville is a diverse city and it’s important that we make sure the services that we provide and the decisions we make create a platform on which we all have a chance to grow and thrive.

The Metro Council is the steward of our environment, our geography, and our entire city; these responsibilities should be taken seriously.

Louisville is among the most dangerous cities in the country for pedestrian collisions and fatalities. What would you do to improve street safety for all road users in Louisville? Please cite specific examples.

We need to foster the slowing down of traffic, not create situations in which we encourage speeding. To this end, I would strongly push that we convert most one-way streets into two-ways. This has been shown to not only accomplish reduction in the speed of vehicles, but to actually help businesses grow!

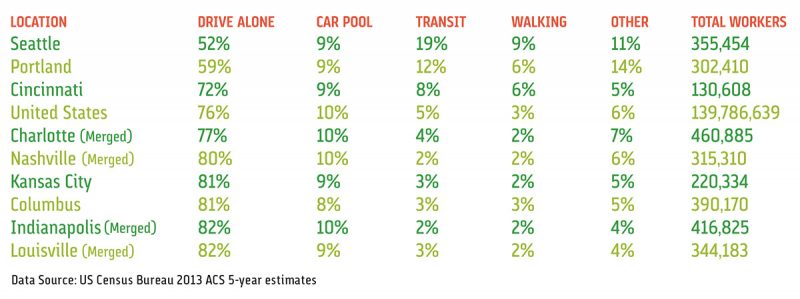

Additionally, I think we should do what we can to get people out of single-occupancy automobiles by thoughtfully creating more bike-lanes (that make work-commutes easier) and putting more resources into pedestrian-based infrastructure (our sidewalks are crumbling!).

What does responsible development look like in Louisville and in your district? What would you do to promote responsible development in Louisville?

First, we need to stop financing sprawl, especially at the expense of our urban core. It doesn’t make any sense to suggest placing developments like the currently proposed soccer stadium on empty green-space when we already have a the old Cardinal Stadium being left to decay (this is only an example).

We need to encourage infill development and respect our history; I believe the greenest building is one that already exists.

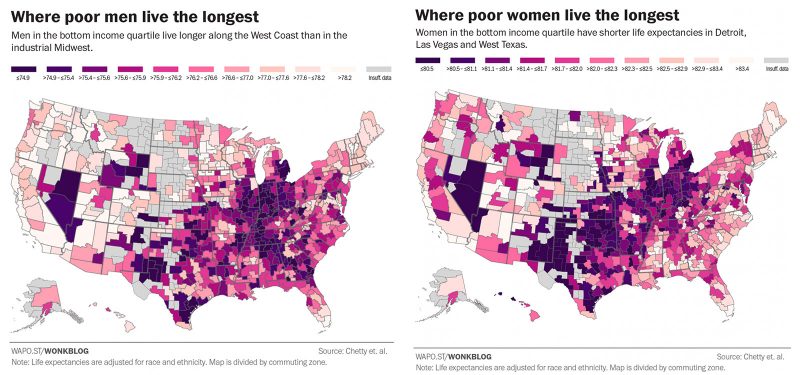

Louisville is among the fastest warming cities in the country. Please describe your stance on fixing Louisville’s Urban Heat Island Effect. What specific steps need to be taken to solve this problem?

We need to stop creating parking lots and move in the opposite direction! Instead of encouraging driving we should make public transit and greener forms of transportation an easy choice to make!

This means expanding our public transit infrastructure (more TARC routes, easier to understand TARC routes, more bus shelters, and maybe even a serious reconsideration of light rail or trolley system).

Additionally, we should continue to partner with groups like Louisville Grows and restore and strengthen our city’s tree canopy.

How would you strike a balance between preservation, development, and economic development in Louisville?

What I would like to see is more of a “win-win” approach when it comes to development. For instance, when we grant a financial incentive to a new development like a hotel, we might pass an ordinance that requires that a percentage of TIF (Tax increment financing) district funds go towards the funding of the Affordable Housing Trust Fund. Through this, we can put vacant houses back into circulation and place people in homes that otherwise would live in substandard housing.

That way we can both restore our historic and vacant properties, both maintaining the character of our neighborhoods, but also creating places to live for our many residents who lack adequate housing.

These sorts of mutually beneficial options are things I would seek to push in Metro Council.

Optional open response. Discuss any issue in Louisville relating to land use, development, transportation, preservation, or health.

I would like to see us tackle both our heroin epidemic and homeless problem by embracing a “housing first” model of transitional housing. It’s a sad fact that many of our homeless population are struggling with drug problems; “housing first” allows these people to be put into homes where they can be targeted and treated for services. This model has been proven to be effective in both getting people clean, but most importantly it allows for an easier reentry into society as productive citizens.

Additionally, I would like to see our city create programming that trains citizens to hold memberships on our city’s boards and commissions a part of its nominating process. It has been a great point of contention that our city’s boards do not adequately reflect the composition of its population. Forming a program that prepares citizens throughout all of our neighborhoods to serve our city will go a long way towards solving this. This has been done in other cities and it works.

Aletha Fields

Did not respond.

Marshall Gazaway

Did not respond.

Barbara Sexton Smith

Have often do you walk to work or for basic errands?

Every day

Have often do you take transit to commute to work or for basic errands?

A few times a month

How often do you ride a bike to get to work or for errands?

A few times a month

How often do you drive in a personal motor vehicle?

A few times a month

How safe do you feel as a pedestrian walking on Louisville’s streets?

Very safe

Louisville’s transit system should expand service, infrastructure, and offerings.

Strongly Agree

The city should invest in complete street design that promotes safety for all road users.

Strongly Agree

Walkable and transit-oriented development should be promoted over auto-oriented development.

Agree

Louisville should repair and maintain its existing transportation network before widening or building new roads.

Undecided

Historic architecture promotes the economic vitality of the Louisville region.

Agree

Describe your favorite walk OR your favorite place to hang out in your neighborhood.

One of my favorite places is the bike path along River Walk and along Portland Canal. And I love to just hang out on the sidewalks where all the people are!

What’s the biggest issue facing your district and how would you address it?

There are many important and pressing issues facing our district. Accessibility to neighborhood jobs, transportation, and affordable and sustainable housing is on the top of that list. The heart of our city and the people who live there need leadership looking to the core problem of: how we are creating a sustainable live/work/play environment for the people who LIVE IN that inner core. Too often the conversation has been how do we draw folks downtown. It is time that conversation turned to how we lift and sustain the people who live here.

In three sentences, what does Metro Council do?

The Metro Council focuses on economic development, education and quality of life by creating ordinances, regulations, policies, and codes to assist in the development of jobs, housing, and services for the residents of this city. The Metro Council also stands as an advocate for the people to those services when standards are not being met. We work together so the interests of every citizen, every neighborhood, are represented when developing plans for a better tomorrow.

Louisville is among the most dangerous cities in the country for pedestrian collisions and fatalities. What would you do to improve street safety for all road users in Louisville? Please cite specific examples.

As someone who walks nearly everywhere I go this is an issue I am personally acquainted with. Greater attention must be paid both behind the wheel and on foot. Addressing this issue must begin with enforcement of our current city ordinances and traffic laws. Speeding, running lights, and jaywalking are all ticketable offenses. Tickets are not there to punish, they are there to remind you to be more mindful of your surroundings. Safer neighborhoods is one of my platforms.

What does responsible development look like in Louisville and in your district? What would you do to promote responsible development in Louisville?

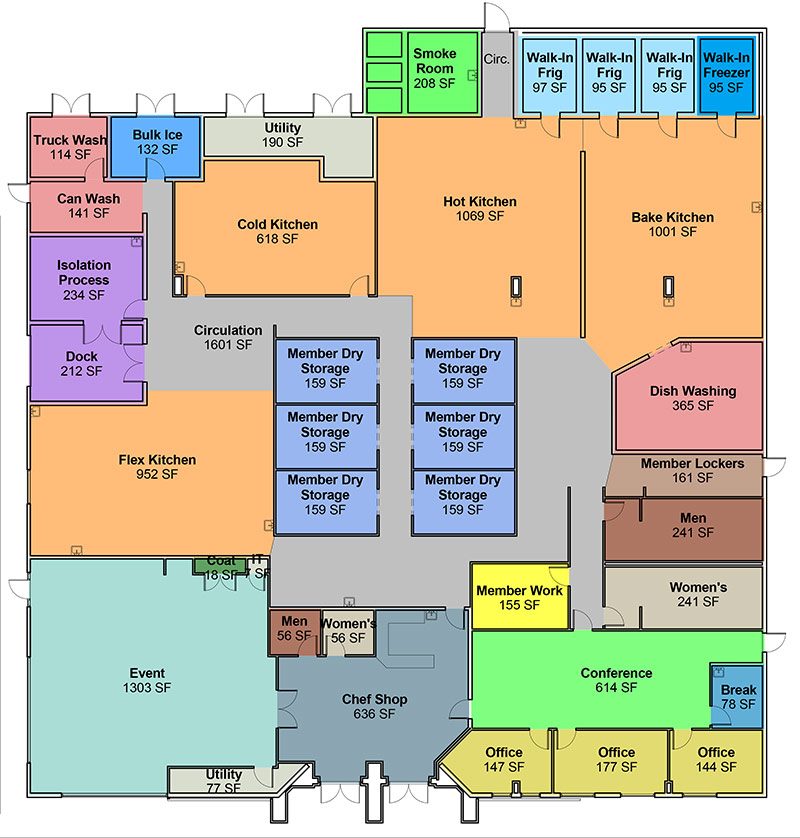

We need local control and local development. From construction to plumbing to the businesses that occupy the spaces we must promote from within. Responsible development means looking to our neighborhoods and asking, will this create jobs for the people who live there? It also means: will this development create affordable housing for the people who live there. Working together with the community we can reclaim our neighborhoods and strengthen our city.

Louisville is among the fastest warming cities in the country. Please describe your stance on fixing Louisville’s Urban Heat Island Effect. What specific steps need to be taken to solve this problem?

Metro Government must seriously evaluate and measure how we are enforcing the air quality regulations we already have. We must enforce and collect fines on current violations. We must hold industry accountable for their actions and end the “look the other way” “Just this once” exceptions that exist within the structure. Fines exist to create balance and offset the cost of repairing harm done.

In addition to enforcement, we have a growing interest in District 4 for community gardening. Working with developers to modify roofs to create new and inviting green spaces will not only help the curb the urban heat island effect, it will promote nutrition, and build community gathering places. This is something we can all agree on!

Attention must continue to be paid to our tree planting programs. This must be a public – private partnership.

How would you strike a balance between preservation, development, and economic development in Louisville?

That balance comes from within. It is one thing to look to other cities and ask, “How can we learn from you?” It is quite another to lose sight of who we are in the process. Louisville is unique and part of economic development is selling that uniqueness as a reason to build here. When preservation can be made it adds to our identity as a city. And when preservation is not possible, we must do a better job of being transparent on those issues and inviting developers to become a part of what makes our community exceptional. We must embrace the interests of our citizens and be generous with the time and attention it takes for all voices to be heard.

Optional open response. Discuss any issue in Louisville relating to land use, development, transportation, preservation, or health.

As a District 4 candidate a focus on reclaiming abandon properties is vital to the livability and economic health of our urban core.

From a Metro Council level we can begin by improving the construction regulations, codes, ordinances and policies that result in unlivable vacant homes. We can fully fund the Affordable Housing Trust Fund. We can hold financial institutions and landlords accountable for the condition of these homes. We can relieve property owners of the expense and liability associated with the home. We can ensure that any earnings from these abandoned homes are used to reclaim other properties in the area. We need LOCAL control, LOCAL development.

These are the easy answers.

The harder answers come in the execution of those ordinances. It always comes down to that on a governmental level. There are always issues that need attention. How do we effectively prioritize those items? How are those decisions made? This is where my experience and connections will help District 4. We are not going to fix this and many other issues with fancy words or sharp tongues. It will only be fixed with hard work and leveraging the resources of this community to their fullest extent.

This requires skillful negotiation strategies and an interest – based approach to problem-solving. Everyone must be heard.