“What you measure is what you get,” the saying goes.

That’s certainly true for transportation policy. And for a very long time one metric has reigned supreme on American streets: “Level of Service,” a system that assigns letter grades based on motorist delay. Roughly speaking, a street with free-flowing traffic gets an A while one where cars back up gets an F.

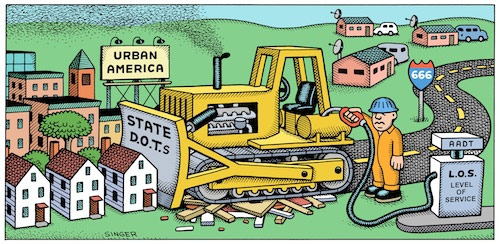

Level of Service, or LOS, is what traffic engineers cite when they shut down the possibility of transitways or bike lanes. It also leads to policy decisions like road widenings and parking mandates. Even environmental laws are structured around the idea that traffic flow is paramount, so they end up perpetuating highways, parking, and sprawl. Because if the top priority is to move cars—and not, say, to improve public safety or economic well-being—the result is a transportation system that will move a lot of cars while failing at almost everything else.

The good news is that there’s a growing recognition inside some of the nation’s largest transportation agencies that relying on LOS causes a lot of problems.

Just last week, the state of California introduced a new metric to replace LOS in its environmental laws. Instead of assessing how a building or road project will affect traffic delay, California will measure how much traffic it generates, period. Car trips, not car delays, will be the thing to avoid. This is likely to have the opposite effect of LOS, leading to more efficient use of land and transportation infrastructure.

Change is afoot at the federal level too. Officials at the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) are looking at how they can spur changes like California’s LOS reform in other places.

Barbara McCann, of the Policy Office of the Secretary at U.S. DOT, told Streetsblog that her agency has been charged with reviewing internal policies that are an obstacle to better biking and walking. “LOS is something that has come up with that,” she said.

Despite what you may have been told, “there is no federal mandate for Level of Service,” she said. The federal government has never compelled state and local governments to emphasize LOS above all. But Level of Service is a deeply ingrained engineering convention. Transportation planners might not be attuned to the value judgments inherent to LOS, or to its flaws.

What FHWA can do is accelerate the adoption of alternatives to LOS. Over the next year or so, McCann says, the agency plans to actively encourage state and local policy makers to consider different performance measures.

As a first step, FHWA will soon release a case study about a local agency that is moving away from using LOS. Then the agency will develop a peer-to-peer exchange, where cities and states can share ideas and experience about shifting to other metrics.

Finally, as required by the 2012 federal transportation bill, MAP-21, FHWA is working on a whole new set of performance measures for American transportation agencies. The law specifies, for the first time, that states DOTs should track how they perform in terms of safety and environmental protection. The law requires state agencies to set goals and report progress toward meeting them.

One of the big unknowns is how the federal performance measures will define “congestion,” which is one of the metrics state DOTs will have to assess. The law does not specify that congestion must be assessed using LOS, but federal regulators could decide to do that—and if they do, not much will change. A much better option would be to use a metric closer to what California is doing—traffic generation, not driving delay.

The rule-making period is currently in progress, and McCann said she can’t discuss details during that time.

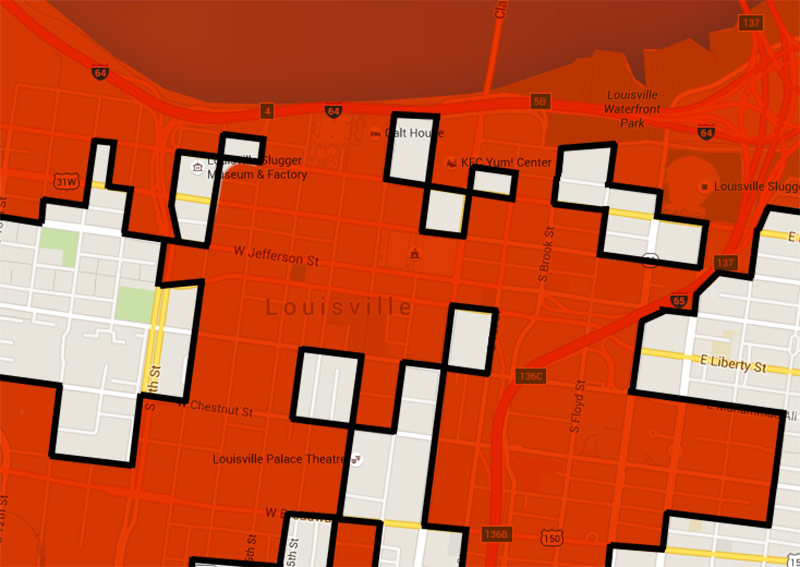

[Editor’s Note: This article was cross-posted from Streetsblog USA. Top image shows Shelbyville Road, which was designed to provide a high Level of Service for motorists (Branden Klayko / Broken Sidewalk).]