[Editor’s Note: Louisville has made some pretty amazing achievements in its first 238 years—but it’s made a few blunders along the way, too. This week, we’re launching a new contributed mini-series documenting eight of the best and eight of the worst decisions, ideas, or projects that have profoundly affected the city. This list is by no means complete—and you may have strong opinions of your own about what should be on the best or worst lists. Share your thoughts in the comments section below. Or check out the complete Best/Worst list here.]

Derby Day, 1948, was the last day of trolley operation in Louisville. What once was an extensive, thriving transportation system has now been relegated to history’s trash heap.

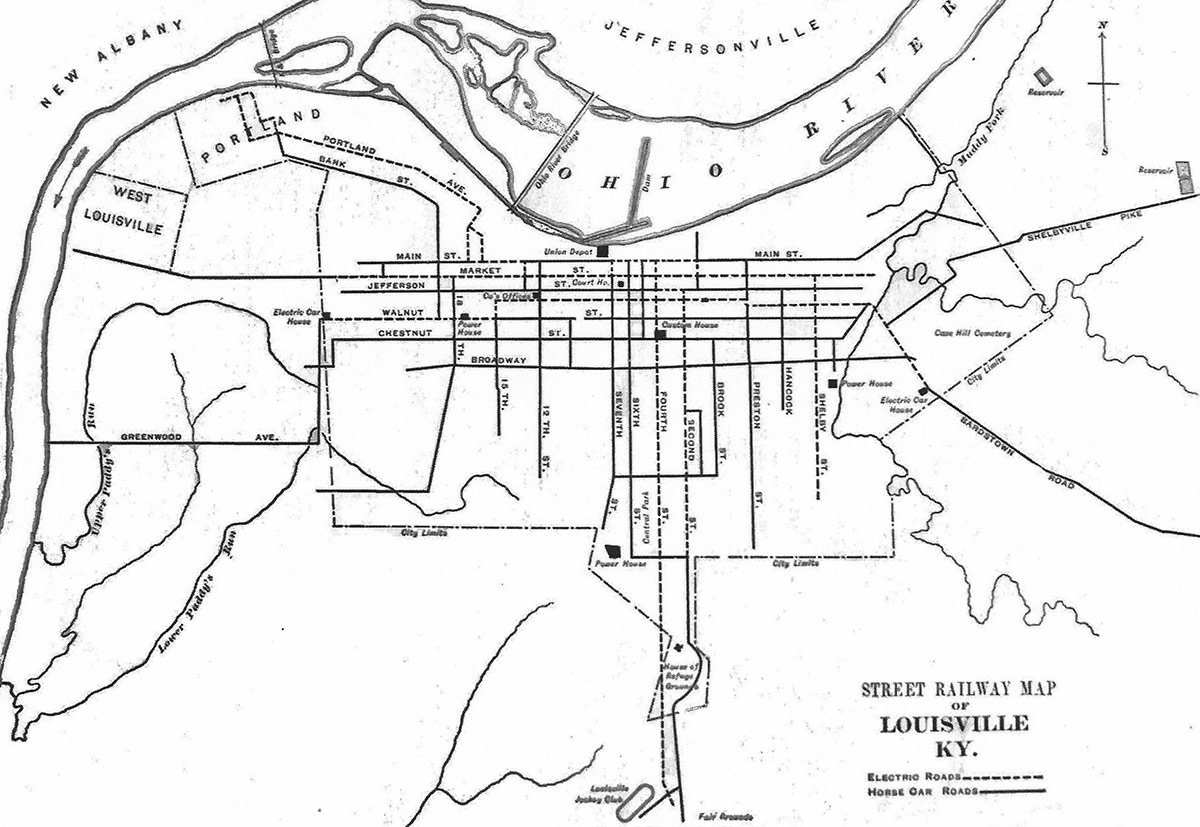

Louisville was home to a Midwest trolley empire that included St. Louis, Indianapolis, Detroit, Cleveland, and more. It was owned by the duPont family, close relatives of the famous duPonts of Wilmington, Delaware.

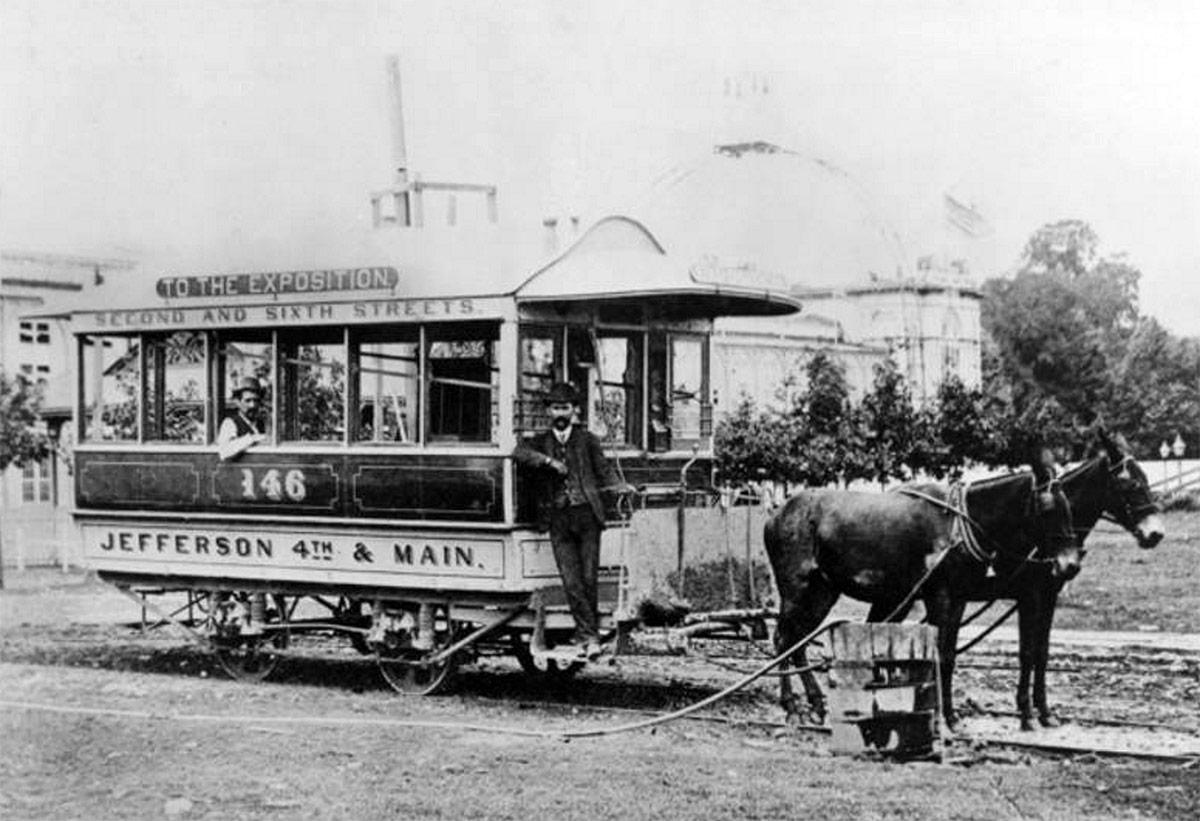

Alfred and Antoine duPont relocated to Louisville in 1854 to seek their own fame and fortune on the expanding western frontier of the United States. They invested in a variety of businesses, but their purchase of a mule-pulled trolley line in 1866 resulted in a regional network of trolley systems.

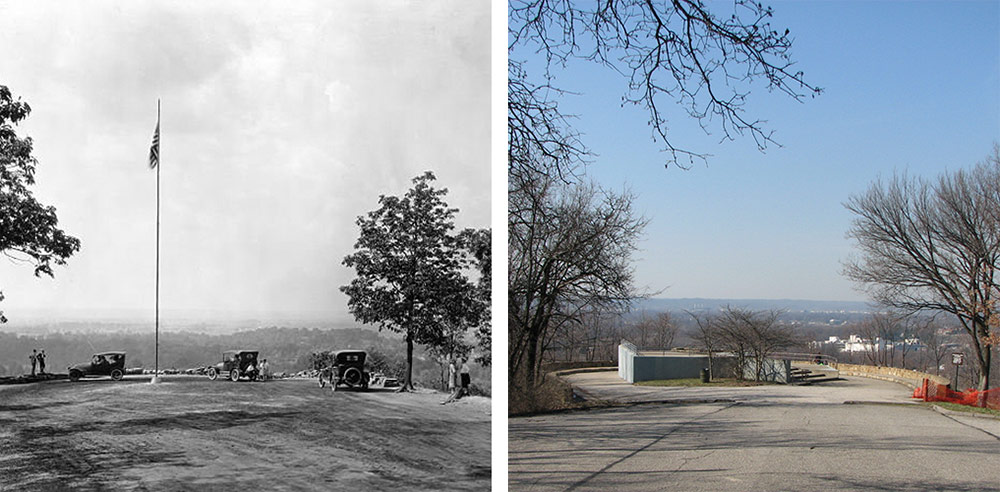

[beforeafter]

[/beforeafter]

[/beforeafter]

When the duPont Company was struggling in the early 1900s and about to be sold, it was the Louisville duPonts who came to the rescue, relocating back to Wilmington. They used their entrepreneurial skills learned here to save the family business and help create the global mega-corporation that it is today. In so doing, they sold their trolley holdings.

By the 1940s, automobiles had eroded trolley ridership to where it was no longer economically feasible to operate. There were no more trolleys running after May 1, 1948.

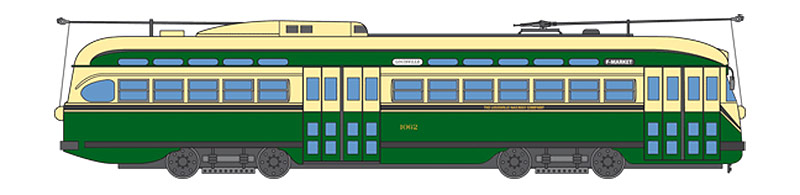

Fast forward seven decades. Trolleys have been supplanted by newer, similar technologies and rebranded as “streetcars” or “light rail.” Fixed-track mass transit is back in business across the country. St. Louis, Atlanta, Nashville, Denver, Kansas City, and others have viable rail transportation. Nearby Cincinnati is in the construction stages for its own.

In Louisville, there have been various studies for a light rail line, but nothing is even close to the implementation phase. Officially, the T2 light rail system proposal was investigated by TARC but is now thoroughly out of date. Most of the discussion of streetcars has come from the community. There have been proposals for a streetcar along Bardstown Road, along Market Street, and, most recently, along Fourth Street. All three of those once existed a century ago.

Instead of disbanding the entire system at once, what if Louisville had retained a select few lines that were still popular and profitable? The elevated “Daisy Line” that ran between Southern Indiana and Downtown across the K&I Bridge certainly would have had a good volume of passengers, and the east-west Market Street and north-south Fourth Street lines also would be popular today.

If Louisville had retained even a fragment of its historic system, it would have made Louisville a national leader in public transportation today.

How would even a single streetcar line or two change the city’s urban growth dynamics? Where you you like to see a rail-based streetcar or light rail line in Louisville today?

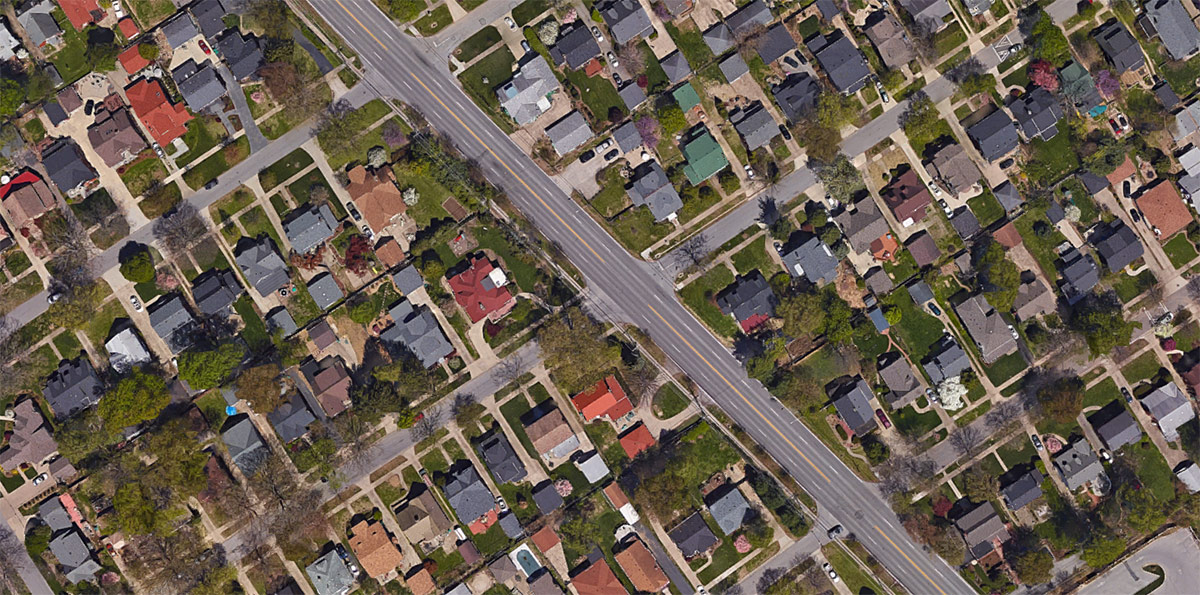

Remnants of Louisville’s trolley heydays exist just below the street asphalt surface. Paved over, these steel rails that once served the bustling network are periodically rediscovered during road repairs. They remind us today of “what if” the trolleys still existed.

[Top image of a stack of trolleys from Los Angeles at the scrapyard courtesy Wikimedia Commons.]