Husband and wife team, Rick and Bella Portaro Kueber, are behind the proposal to build six shipping container apartments on the corner of Shelby Street and Ash Street. Plans for the so-called Schnitzelburg Container Homes were unveiled last month to much excitement.

Rick is the CEO of Sun Tan City and Bella is owner of social media and marketing company Bella Vita Media. While Rick has developed commercial properties in the past, the Container Homes are a first for the team—and for the city. And they hope to make a splash with a high quality product.

With an anticipated completion in October, the team hopes to partner with this year’s IdeaFestival to showcase the innovative design and give tours. The development concept is new to the city, and the Kuebers believe that being first to market with the idea is a real opportunity to push boundaries in Louisville.

Broken Sidewalk Editor Branden Klayko spoke with Rick Kueber about the project to learn more about the city’s newest housing type: the shipping container apartment.

Broken Sidewalk: The idea of shipping container apartments is an intriguing idea. How did you come up with the concept?

Rick Kueber: My wife and I were in Austin, Texas, and we visited a concept called The Container Bar. That spurred a conversation locally with Gant Hill about containers and he had introduced me to Jeremy [Semones] at Core Design.

The conversation really spurred from there. They were really interested in doing this project and building some container homes. I told Gant that if we could find the right land I would be interested in doing it as well. And we went from there.

How did you settle on the Schnitzelburg site?

We looked at a number of different options in different areas—Downtown and Clifton and this site in Schnitzelburg.

The Germantown and Schnitzelburg area is pretty much the hottest real estate market in town. We’ve seen 50 to 100 percent gains in home values in that area in the last 24 months.

You’ve got the Germantown Mill Lofts right across the street which is prepared to open. I think that’s going to provide a lot of momentum on top of what’s already there. We’re talking hundreds of new occupants and residents on the streets on a nice day. It’s really going to change that area.

It’s a very livable area. You’ve got a lot of great bars and restaurants. You’ve got several grocery options relatively close. If you look at the proximity to both the University, Downtown, the Highlands, it’s a very convenient area to live in.

Walk us through the development proposal. Where does the project stand? What needs to happen next?

We purchased three lots that are approximately 25 by 150 feet—these are shotgun home lots. I think they’re 0.7 acres; they’re very small lots. We’d like to do two, 500-square-foot units per lot. We’re at the intersection of Ash and Shelby and they would line up with both streets.

We’re right on the border of what I would call the industrial / residential area. Just to the north of us there’s a lot of steel warehouses and these are the last three lots on Ash Street which are traditional Germantown homes.

My architect, Mark Foxworth with Foxworth Architecture, lives in the area about two blocks from there, so he’s really familiar with the neighborhood. He’s done a really good job with the proposal.

Right now, there are still some remaining questions. The property is zoned R-6, which is multi-tenant, but there are some restrictions based on density and the size of the lot. Right now we’re reviewing that. We’ve had a few meetings with the city, and we’re probably going to have to rezone to R-7 because the lots are pretty small.

The next step for us is to rezone to R-7, and we should have that filed in the coming weeks. It would be our hope and desire to have this project wrapped up by October in time for IdeaFestival.

Are there any special considerations to designing container units?

They’re not really treated any differently than a normal steel structure. I think the unusual nature of the structure will provide some challenges for the city, but I’ve gotta say the city has been, since the announcement, very helpful. They understand the significance of the project and container homes in general. They’d love to see more container homes built in the city.

What kind of person do you see living in this kind of a unit?

These are going to be really functional, minimalist units by nature of their size, but they’re going to be also a bit trendy. It’s a first to market type of unit. A lot of young professionals I think would look at living in something like this if they work Downtown or if they’re going to grad school or medical school at the University of Louisville.

Being that they’re first to market, I think there’s going to be so much interest. We’ll figure that out as we go. If you look at the general makeup of the Germantown / Schnitzelburg area, I think we’ll stay right in line there. I don’t think these will attract much different people than are already in the area. It’s a pretty vibrant area already.

We’ve had a lot of interest already in the units—people reaching out via Facebook—asking what they’re going to rent for and how to rent one.

Do you have answers to those questions about when they might be for lease or what they’ll rent for?

A lot of it’s going to depend on the final numbers and the final investment dollars required, but we think they’ll be in the market rate of somewhere between $800 and $1,200 a month.

What will it be like to live in the Schnitzelburg Container Homes?

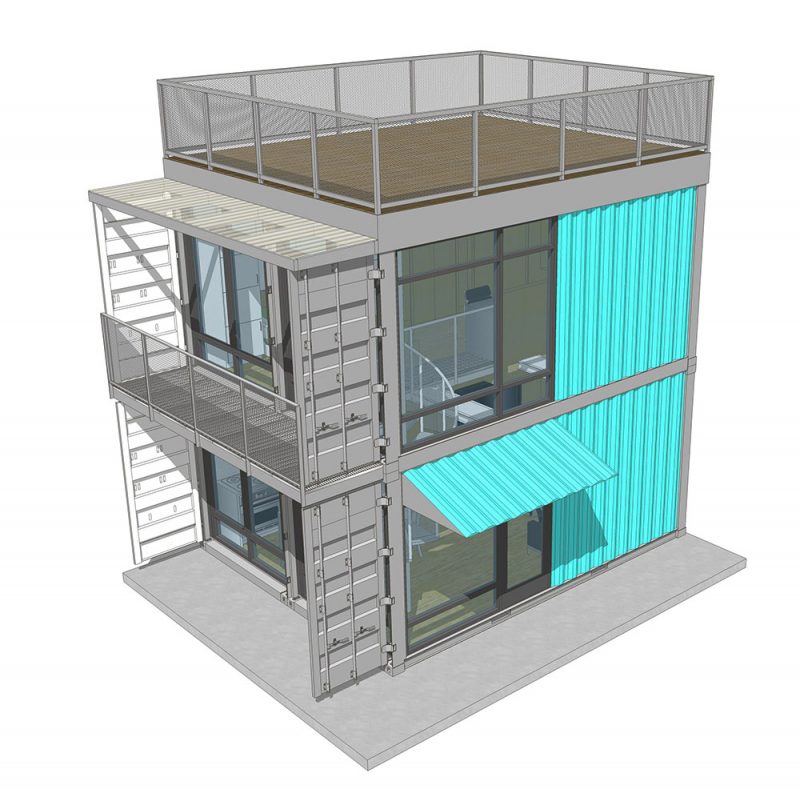

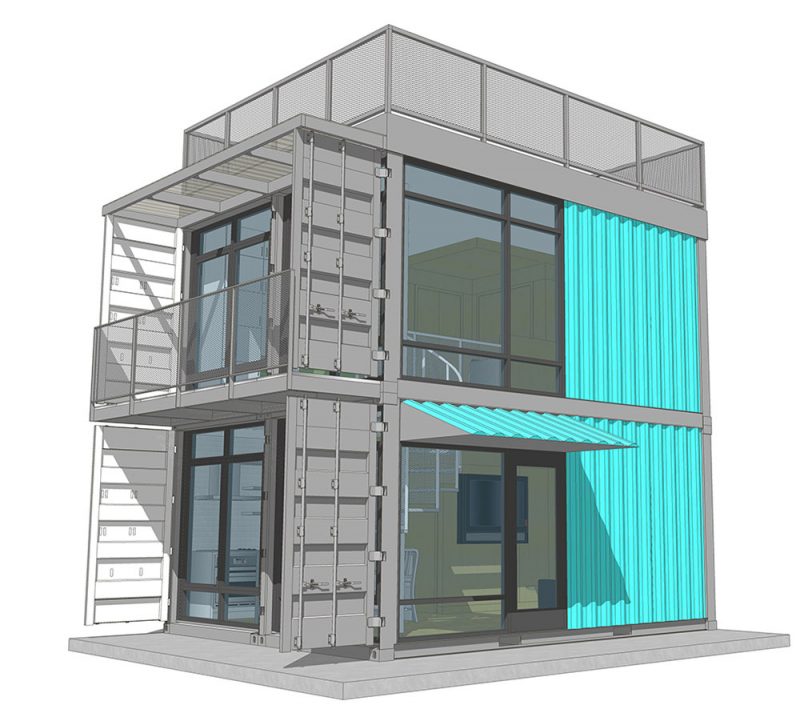

We intend to use four, 8-foot-by-20-foot containers—which are half containers—and piece them together. It would be 640 square feet total with one-and-a-half bathrooms, a spiral staircase leading to the second floor, and another staircase leading from the balcony to the rooftop deck.

I want these to be first class living spaces. They’re certainly going to have an open floor plan, a loft-style floor plan. They’re going to be very nice units.

They are smaller spaces, but I wouldn’t call this a tiny home. I would call this more of a minimalist home. It’s not quite 300 or 400 square feet. We’re talking 640 square feet plus a rooftop, so you’re going to have 1,000 square feet of living space.

The outdoor living spaces are just as important as the inside living space on smaller units. I told the designers, that the third floor rooftop deck was the dealbreaker for me—we have to have the rooftops. I think it opens up the spaces.

With the positioning of these units in the neighborhood, if you have that third-level rooftop deck, you’re going to have great views of sunsets, a great view of Downtown Louisville in the evening because of the proximity.