It’s official! Smoketown’s Logan Street CSO Interceptor, a project by the Metropolitan Sewer District (MSD) to fix Louisville’s combined sewer overflow (CSO) problem, is going to be built at grade with a park on top. And that’s good news for much more than the Smoketown neighborhood in which the project sits.

Monday’s unanimous decision by the MSD Board of Directors dates back seven years to 2009 when the project was announced. Louisville, like most other cities in the country, is under a consent decree with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to get its act together about raw sewage dumping into local waterways when the city’s older sewer system is inundated by rainwater. (Newer parts of the city, typically the suburbs, have a separate sanitary and storm sewer system.)

What’s a CSO basin?

The Logan Street CSO Interceptor is one of 12 concrete basins slated for various parts of the city. Essentially, these enormous sealed buckets hold the offending CSO—millions of gallons of it each—until the sewer system is able to handle operations normally. The basin’s contents are then pumped back into the normal sewers on their way to treatment.

The Smoketown facility is planned to handle CSO events in the region of the South Fork of Beargrass Creek.

But Smoketown’s 17-million-gallon facility, the first of the bunch planned in 2009, was designed differently. Where the subsequent 11 basins are all designed as at-grade facilities, minimizing their impact to their surroundings, the Logan Street and Breckinridge Street basin was planned as an enormous windowless warehouse sticking up like a sore thumb on a prominent site in the neighborhood.

A sleeping giant awakened

Needless to say, locals began to ask questions as construction began blasting the neighborhood. Neighbors began to talk and meetings were held to discuss the project, such as at the Smoketown Neighborhood Association.

“I do think that it really was a combination of grassroots advocates saying for a long time, this is not acceptable,” Ben Carter, an attorney whose office is a block from the basin site, told Broken Sidewalk this week. “ They said, explain this to us again. We don’t understand why this is being built this way.” And after a while support and neighborhood determination grew. “That made way for Reverend Williams [of Bates Memorial Baptist Church] to come into the conversation,” Carter added, noting how the prominent community leader gave gravity to the neighborhood’s pleas.

Carter, who began attending meetings about the basin last November, penned his own call for MSD to reinvest the $4 million price difference between the original raised basin and the 11 other at-grade facilities back into the neighborhood.

“This is an issue of environmental justice. And racial justice, and economic justice,” Carter told Broken Sidewalk this week. “That’s why I went to law school.”

MSD, which admitted mistakes were made in the Logan Street basin process, offered to defer around $700,000 allocated for bricks in the bunker design for a new use and brought in architecture firm De Leon & Primmer Architecture Workshop to work with the community on redesigning the raised facility.

At that facade redesign meeting, Rev. Williams made a speech about why he refused to participate in the redesign process, and over 100 Smoketown residents walked out of the public meeting. A letter signed by the Smoketown Neighborhood Association, Rev. Williams, Ben Carter, and Stephen Kertis of Kertis Creative was sent to MSD Executive Director Tony Parrott outlining the neighborhood’s position and requesting more significant changes to the project.

Tensions were growing and Metro Louisville and MSD responded quickly after meeting with community leaders. Mayor Greg Fischer and Parrott held a press conference where they outlined a plan—requiring MSD board approval—to negotiate a redesign the Logan Street basin as an at-grade facility topped with a park. It was beginning to look like the neighborhood had won the fight.

“We’ve been looking hard over the past several days to find an option to build at grade,” Parrott said in March, noting that the current point in construction is the perfect time to move in a different direction. “We’re in the preliminary phases of planning the solution and negotiating with our contractor,” he said.

The MSD board gave Parrott the necessary authority to negotiate a change order for the project, paving the way for this week’s crucial vote on whether MSD would allocate the millions more in funding to redesign the project. Whatever was to happen, the Smoketown basin is legally required to be operational by December 2017 according to the federal consent decree—timing was critically important.

The Meeting

As we mentioned above, the board voted unanimously Monday to approve the added expenditures and proceed with an at-grade, park-topped basin design.

“As the board, we must balance our responsibility of being good stewards of our ratepayers’ investments in MSD, the voices of the community, and the needs and concerns of the neighborhoods we serve,” Cyndi Caudill, MSD board chair, said at the meeting. The board room was packed to standing room only, and many community leaders were present, including Rev. Williams, Carter, Theo Edmonds, District 4 Metro Council candidates, and many others.

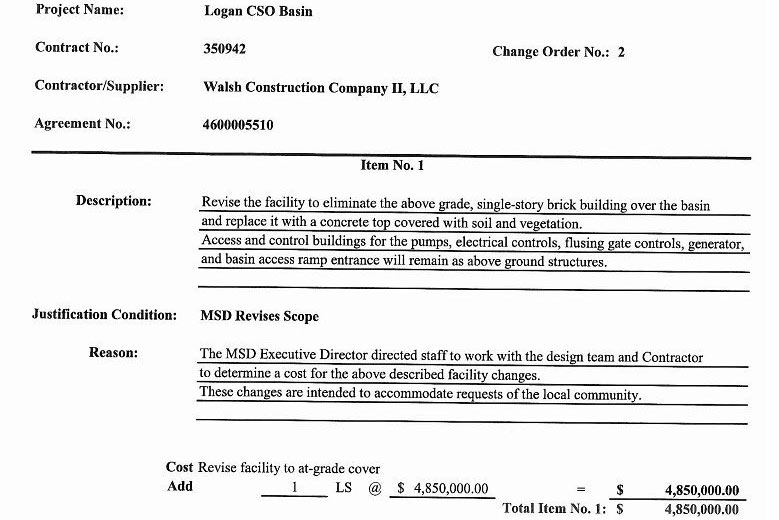

Parrott updated the board on the project status: “We have been negotiating with our contractor, Walsh Construction, and in your board packet you have Change Order #2 that includes major revisions to the facility,” he said, “by eliminating the proposed exterior, one-story brick building that covers the structure and replacing it with an at grade vegetated concrete cover.”

The total price tag for the change came in at $4.85 million, remarkably close to the price difference between this basin and others in the city.

With that brief update, the eight-member board was ready to vote. A motion was made and seconded, no further discussion was requested, and the vote was tallied as unanimous. With that official gesture, the crowded board room erupted in applause.

“I’m pleased we could make the change to put the basin underground,” Board Chair Caudill said following the vote. “And while this contract change will represent an increase in the total cost of the project, I view this as a sound investment in our water infrastructure and towards our overall goal to improve the community in which MSD resides.”

Reflection

With that vote, there’s big change coming to the area—and not just Smoketown. The basin actually sits at the confluence of four neighborhoods—Smoketown, Germantown, and Paristown Pointe, and Shelby Park. Each stands to benefit from the new public park that will be created on top of the basin, and each will be a better place now that the blight-inducing raised basin design is history.

Carter, who had seen the passion of the neighborhood first hand at meetings, noted the somewhat anticlimactic nature of how the long-fraught process was ultimately resolved in a beige board room. “It was very bureaucratic,” he said. “It was simply an agenda item on the meeting.”

“I was thinking about it Monday: It’s interesting to me that all of this organizing and the meetings and things like that culminate in what is essentially the most bureaucratic ‘aye’ vote possible,” Carter said. “The agenda item, it’s just text. As an English major, I love the idea that this text here means the difference between a warehouse or a park. But at the same time, there was applause at the end of it. The people who were there cared about it.”

It’s that effort to simply care about one’s neighborhood that paid off in a big way this week. For decades, Smoketown has been left out, forgotten, and the recipient of many projects of the same ilk as the original bunker basin. But Smoketown is changing fast and learning for itself that it matters as much as Downtown or St. Matthews. It’s exciting to see that kind of transformation happen because it’s a signal that even more and better change is ahead. And walking around Smoketown, it’s clear to see that the momentum is building.